Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a pathological condition similar to alcohol-induced liver damage, while in the absence of alcohol abuse. It encompasses a wide spectrum liver injury ranging from simple steatosis, steatohepatitis, advanced fibrosis to cirrhosis, and has appeared as a worldwide public health problem with a growing incidence and prevalence (1-3). The estimated prevalence of NAFLD is 20% to 30% in adults, 2.6 to 10% in children and 75% in obese and diabetic (1-3).

Outcomes of NAFLD include, not only the development and progression of chronic liver diseases (3,4), but also the risk enhancement of developing cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus (5,6). Current evidences suggest that NAFLD is positively correlated with the morbidity and mortality of many liver complications including hepatocellular carcinoma (3,4). Though diagnosis of NAFLD is insufficient to predict cardiovascular disease (7), increased NAFLD is associated with an enhanced risk of incident cardiovascular disease (5). Moreover, the leading cause of death in patients with NAFLD is cardiovascular disease, and both NAFLD and cardiovascular disease share similar risk factors and treatment strategies (5,8,9).

In recent years, there is abundant evidence for the potential links between NAFLD and kidney function. A series of cross-sectional studies indicate that NAFLD, diagnosed by either ultrasonography, liver enzymes or biopsy, is independently associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) (10-14). Some prospective studies also display that NAFLD, especially with elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase concentration, contributes to CKD development (15,16). Intriguingly, according to the National Kidney Foundation Practice Guidelines (17,18), mild kidney function damage (MKFD) occurs early before CKD appearance, and the adverse outcomes of CKD may be prevented or delayed if MKFD can be detected and treated in time. In this context, MKFD is more important than CKD in health care. However, there is still no large population study to explore the potential relationship between NAFLD and MKFD after adjusted for blood glucose and other confounding factors.

For these reasons, we tested the hypothesis that NAFLD is associated with MKFD under controlling the effects of confounding factors, including age, gender, lifestyle factors, blood glucose, blood lipids, and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). As a result, serum levels of above-mentioned factors were analyzed from the volunteers, and questionnaire and physical examination were performed to explore the potential association of NAFLD with kidney function.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

NaCl, Na2HPO4 and other common used reagents (analytical grade) were from Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd., (Shanghai, China). Water was produced using a Milli-Q Plus purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

Participants and questionnaire

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hunan Normal University. All volunteers signed informed consent forms before their inclusion in the project.

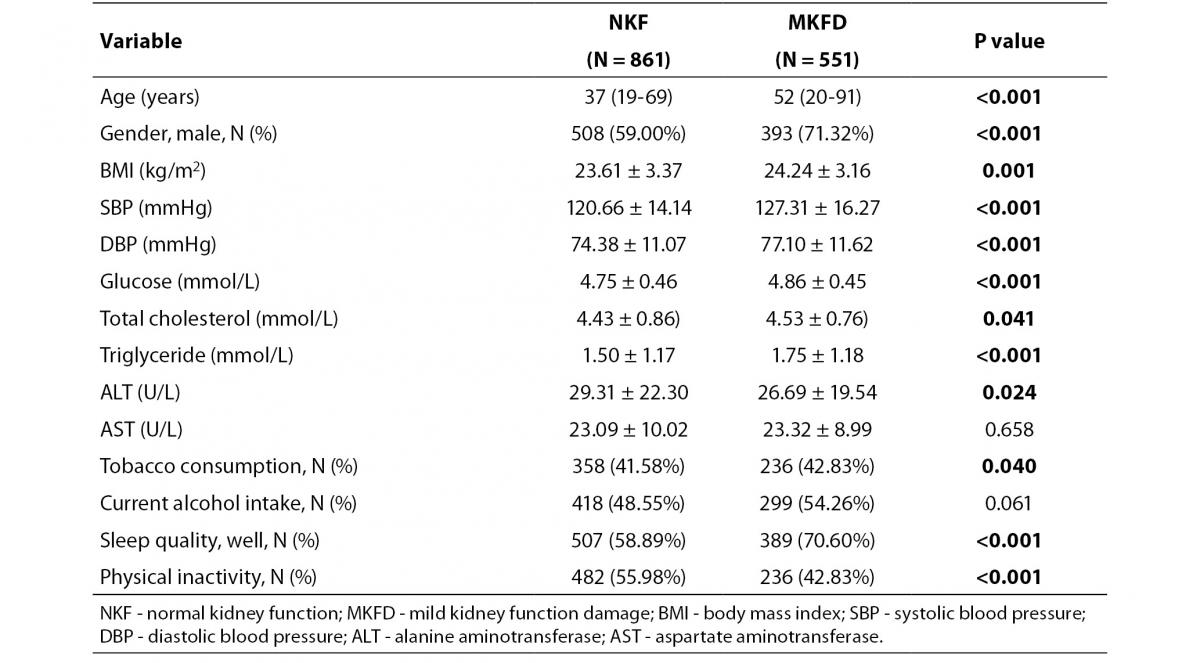

From April 2009 to December 2010, a consecutive unselected recruitment was applied to recruit the subjects from those attending our institution. The total study subjects consisted of 2169 Chinese Han adults of both genders living in the urban area of Changsha City in the Central Region of China. After excluded the subjects missing covariate data, with hepatitis, autoimmune responses, metabolic or hereditary factors or serum levels of fasting glucose higher than 6.10 mmol/L, or with drugs or toxins, 1412 adults were included in analysis. The basic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

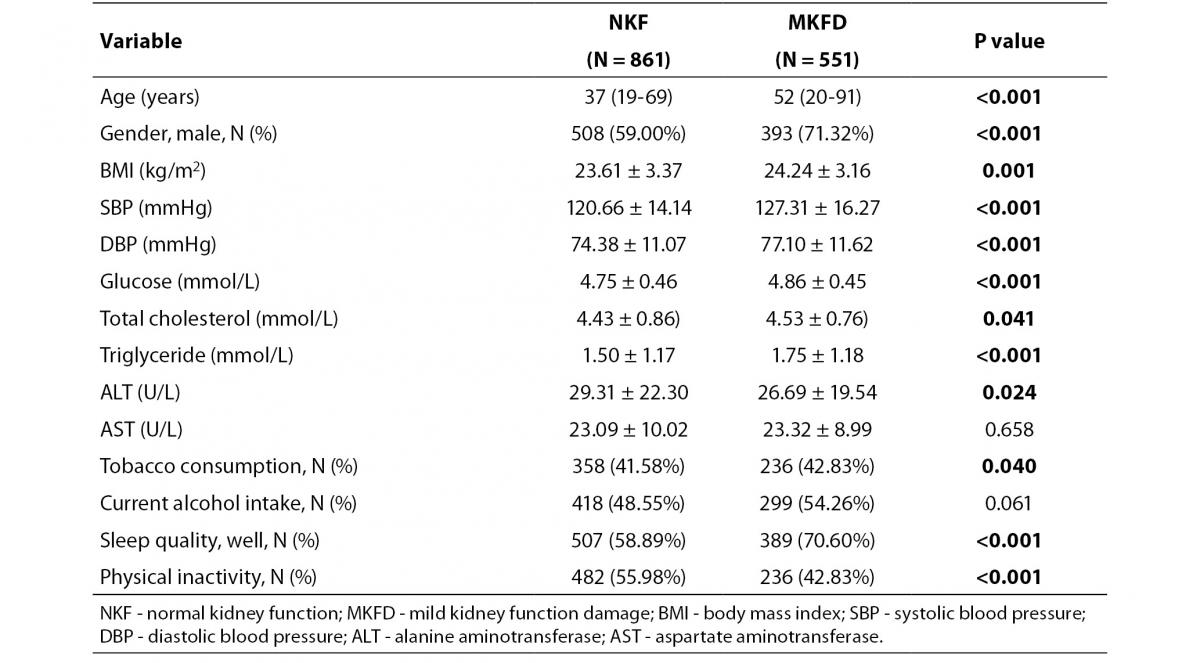

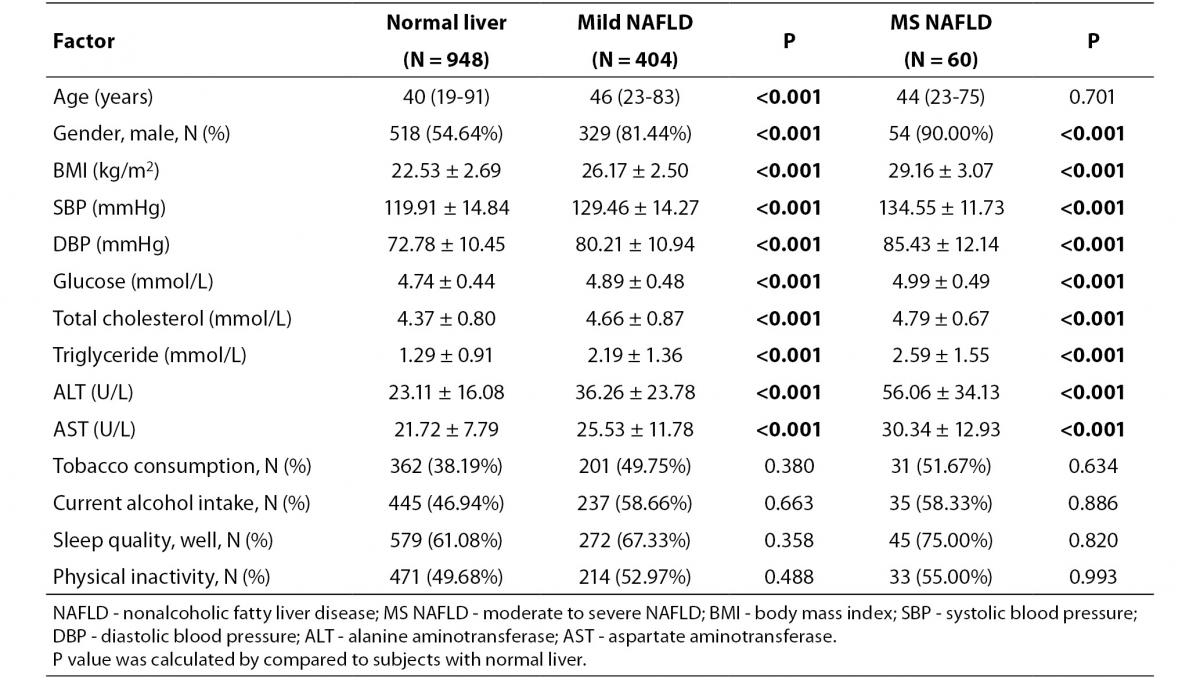

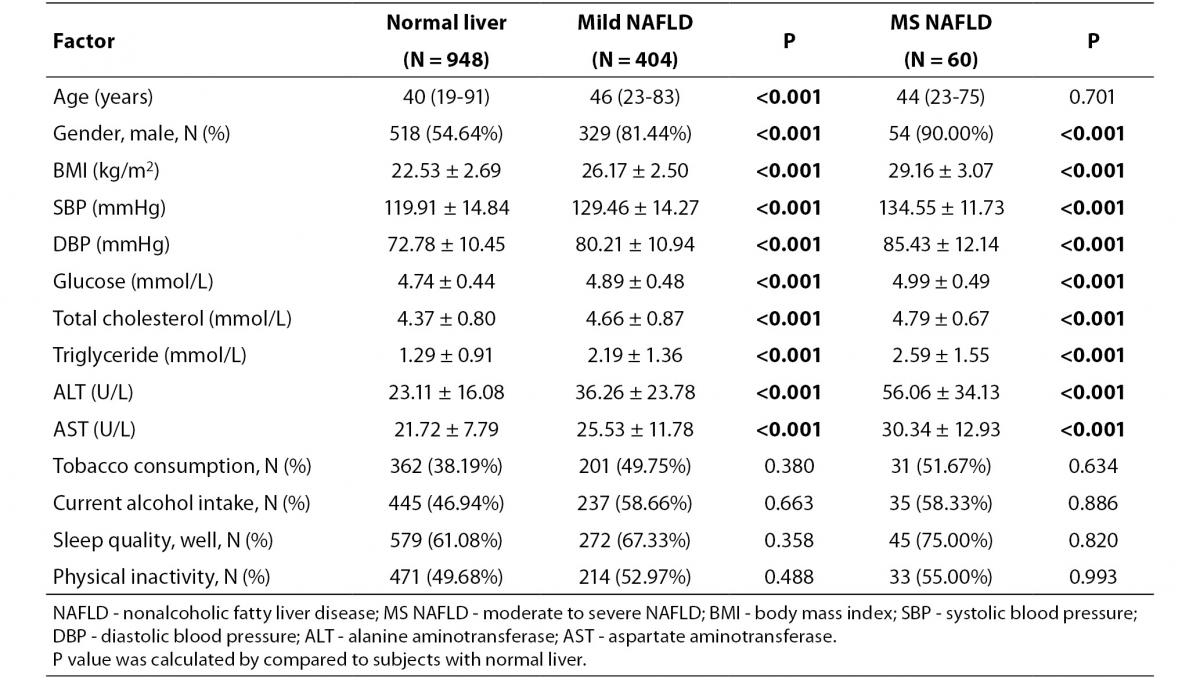

Table 1. Basic characteristics of participants.

The questionnaire recorded information on demographics (age and gender), lifestyle habits (sleep, smoking history, drinking history and physical activity), and detailed medical history. The questionnaire included five possible aspects for sleep quality: well, insomnia, dreaminess, restless sleep, and other problems. Subjects were not classified into sleep with some problems only when the answer was sleep well. The questionnaire for smoking history included five possible aspects: never smoking, sometimes smoking, frequently smoking, stop smoking for less than 1 month and stop smoking for more than 1 month. Subjects were not classified into smoking only when the answer was never smoking or stop smoking for more than 1 month. The questionnaire for drinking history included four possible aspects: never drinking, average drinking per week for bear is __ cup or __ bottle, average drinking per week for wine is __ cup or __ bottle, and/or average drinking per week for liquor is __ cup or __ bottle. Subjects were not classified into drinking only when the answer was never drinking. The questionnaire for physical activity included four possible aspects: never participating exercise, participating exercise for ≤ 1 h/week, 1-3 h/week or >3 h/week.

Blood sampling

Blood samples (5 mL) from the median cubital vein on the inside of the elbow were collected into vacutainer tubes (Becton Dickinson Medical Devices Co Ltd, Shanghai, China) containing K3-EDTA, according to standard blood collection procedures (19,20), and stored at 0-4 °C. All detections were carried out within 8 h of sampling.

Physical examination

Stature, body weight and body mass index (BMI) were detected using an ultrasonic body scale SK-CK (Sonka Electronic Technologies Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The BMI cut-off point for overweight was 25 kg/m2, as advocated by the World Health Organization (21).

After resting for 30 min, each participant’s blood pressure was measured three times in the sitting position, with the right arm relaxed and well supported by a table, at an angle of 45° from the trunk, using an automatic electronic sphygmomanometer (Ken2-BPMSP-1; Pengcheng Healthcare Products Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China).

According to our previous study (22), blood lipids (serum total cholesterol and triglyceride), fasting glucose, kidney function (serum creatinine), and liver function (AST and ALT) were measured using a chromatographic enzymatic method in a MINDRAY automatic analyzer BS-40 (MINDRAY Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China). Serum hepatitis B viral antigens and antibodies were detected by Microplate reader MR-96 (MINDRAY Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China).

Based on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation (23), subjects with fasting glucose concentration over 6.1 mmol/L were excluded from the dataset.

According to the guidelines of the Chinese Society of Hepatology (24), the diagnosis of NAFLD was based on ultrasonic examination using a MINDRAY DP-9900 Plus Digital B/W Ultrasound System (MINDRAY Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China). In detail, the followed five items were examined by a professional physician: 1) diffuse enhancement of near field echo in the hepatic region (stronger than in the kidney and spleen region) and gradual attenuation of the far field echo; 2) unclear display of intra-hepatic lacuna structure; 3) mild to moderate hepatomegaly with a round and blunt border; 4) color Doppler ultrasonography shows a reduction of the blood flow signal in the liver or it is even hard to display, but the distribution of blood flow is normal; 5) unclear or non-intact display of envelop of right liver lobe and diaphragm. The subject displayed item 1 and any one of items 2–4 was diagnosed as mild degree of fatty liver; displayed item 1 and any two items of items 2–4 as moderate fatty liver; displayed items 1 and 5 and any two of items 2–4 as severe fatty liver.

The inclusion criteria for NAFLD were no history of drinking alcohol, or weekly ethanol intake < 140 g in males and < 70 g in females, and without other causes including hepatitis, autoimmune responses, metabolic or hereditary factors, and drugs or toxins (3,24,25).

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from serum creatinine using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula (26). Based on eGFR, kidney function was categorized according to the National Kidney Foundation Practice Guidelines (17,18): normal kidney function (eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 and no proteinuria), MKFD (eGFR = 60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2or with proteinuria).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis of data was done using predictive analytics software (PASW) statistics 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Figures were drawn by Origin Pro 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA). As data showed a normal distribution, parametric statistical methods were used. For comparison of the groups (different physical activity levels), one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was performed. To assess significant F-ratios obtained by analysis of variance, the least significant difference (LSD) or the Tamhan’s T2 post-hoc test was used. The associations between NAFLD and eGFR levels were analyzed by Spearman partial correlation with or without adjusting for age and other covariates. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of MKFD associated with different NAFLD levels were examined using multinomial logistic regression (27) adjusting for the potential confounding effects of age, gender, alcohol intake, tobacco consumption, sleep quality, physical activity, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood glucose, and serum levels of cholesterol, triglyceride, ALT and AST. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

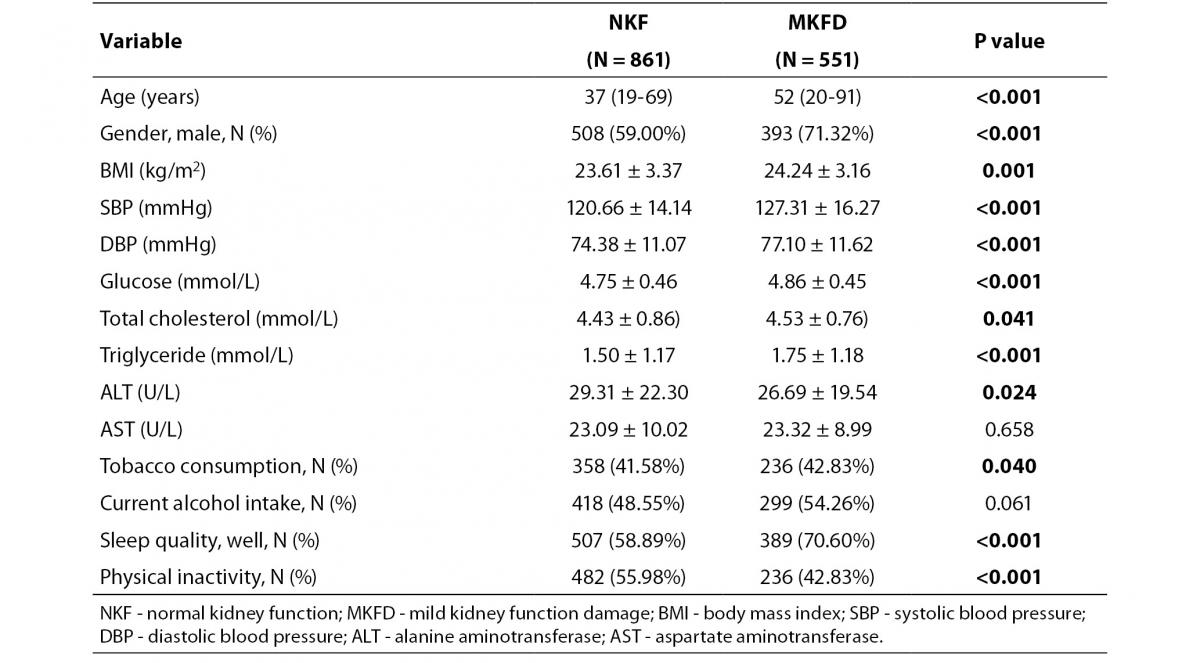

There were significant differences in age and most factors of physical examination among the subjects with normal kidney function and with MKFD (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

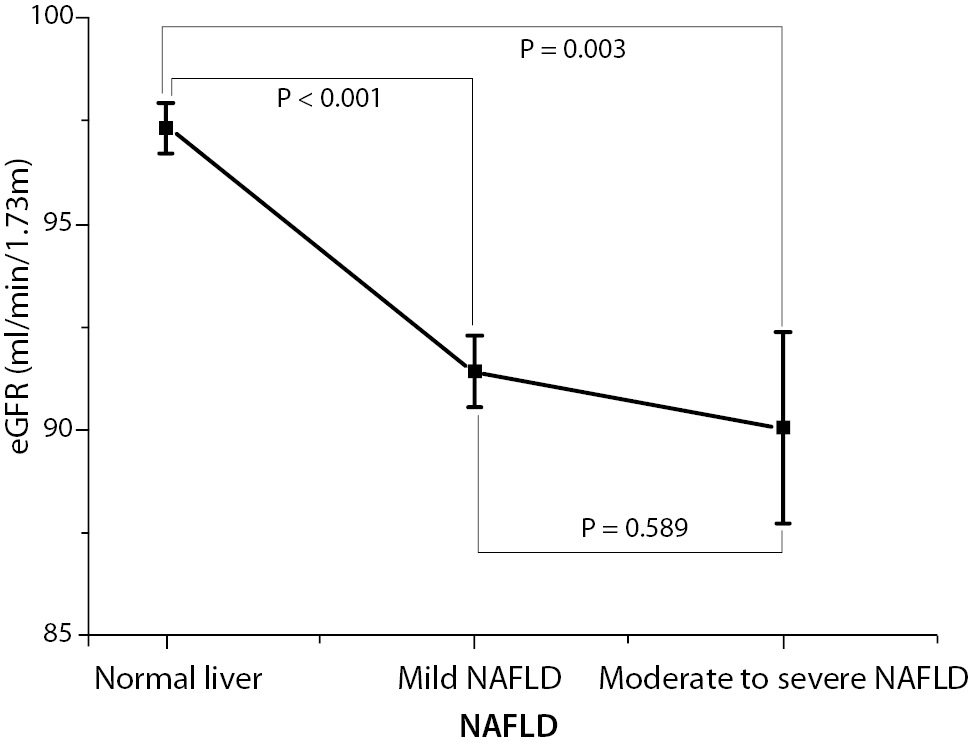

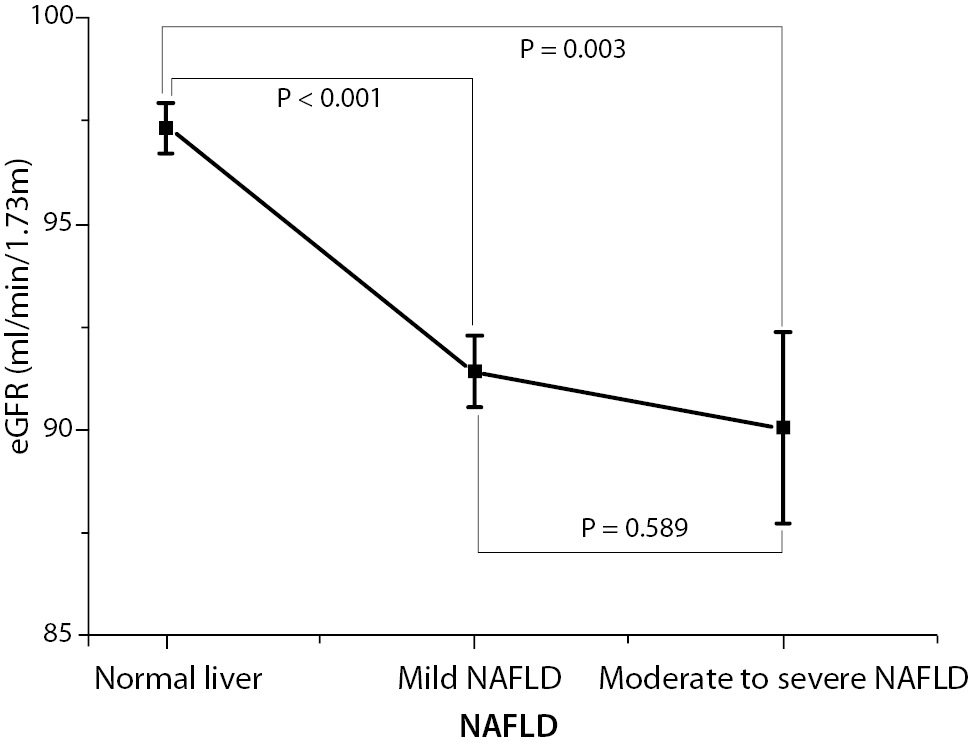

Figure 1. Association of NAFLD and eGFR. Indicated by means (n) and SE () of eGFR levels according to normal liver subjects, mild NAFLD and moderate to severe NAFLD. NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. As the P value for the test of homogeneity of variances was 0.130, all P values in this figure were based on the LSD post-hoc test.

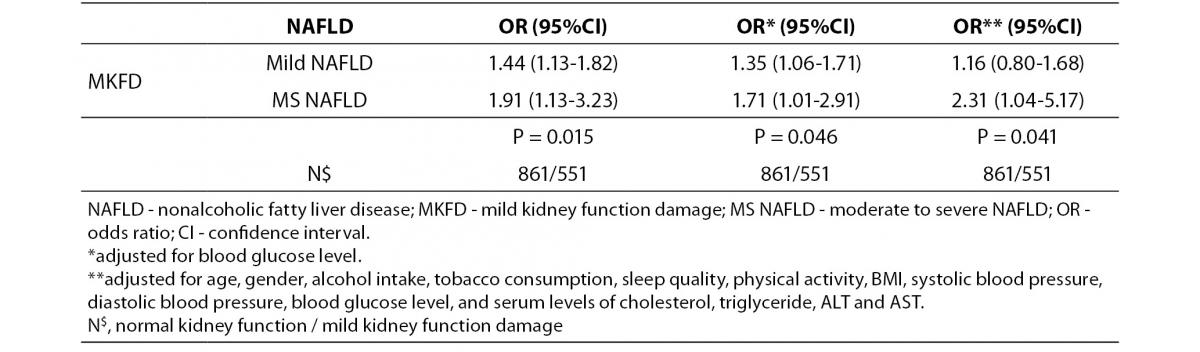

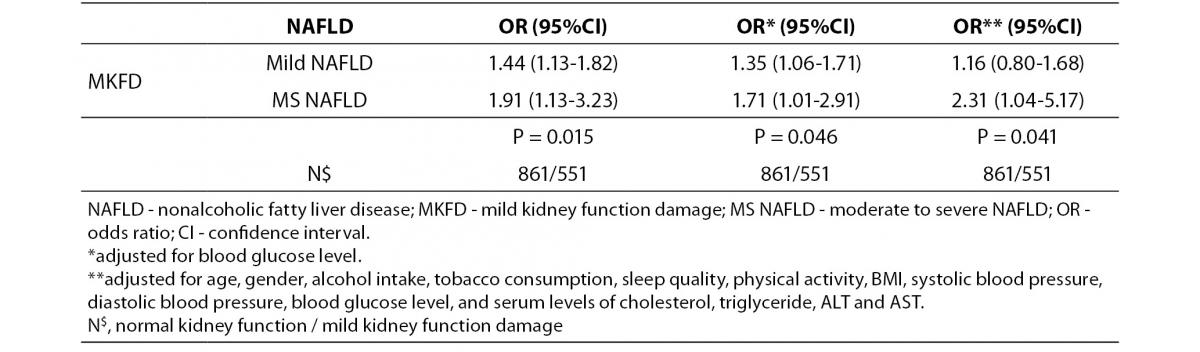

As indicated by eGFR, NAFLD was associated with impairment of kidney function (Figure 1). Further analysis from multinomial logistic regression also confirmed this result. The trend of MKFD was positively associated with enhancing levels of NAFLD (multivariate-adjusted OR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.04-5.17, for moderate to severe NAFLD vs. normal liver, P for trend = 0.041) (Table 2). With or without adjusted for age, gender, alcohol intake, tobacco consumption, sleep quality, physical activity, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood glucose, and serum levels of cholesterol, triglyceride, ALT and AST, results did not substantially change (Table 2).

Table 2. The OR and adjusted OR of MKFD associated with different NAFLD levels.

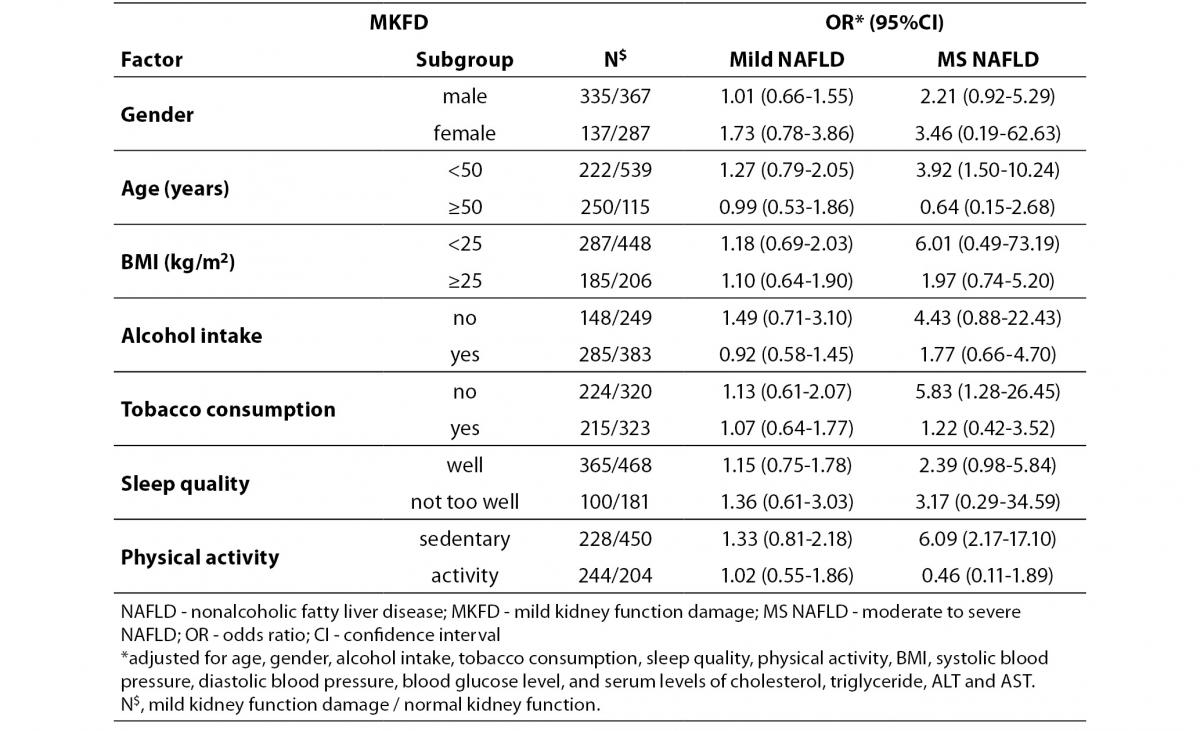

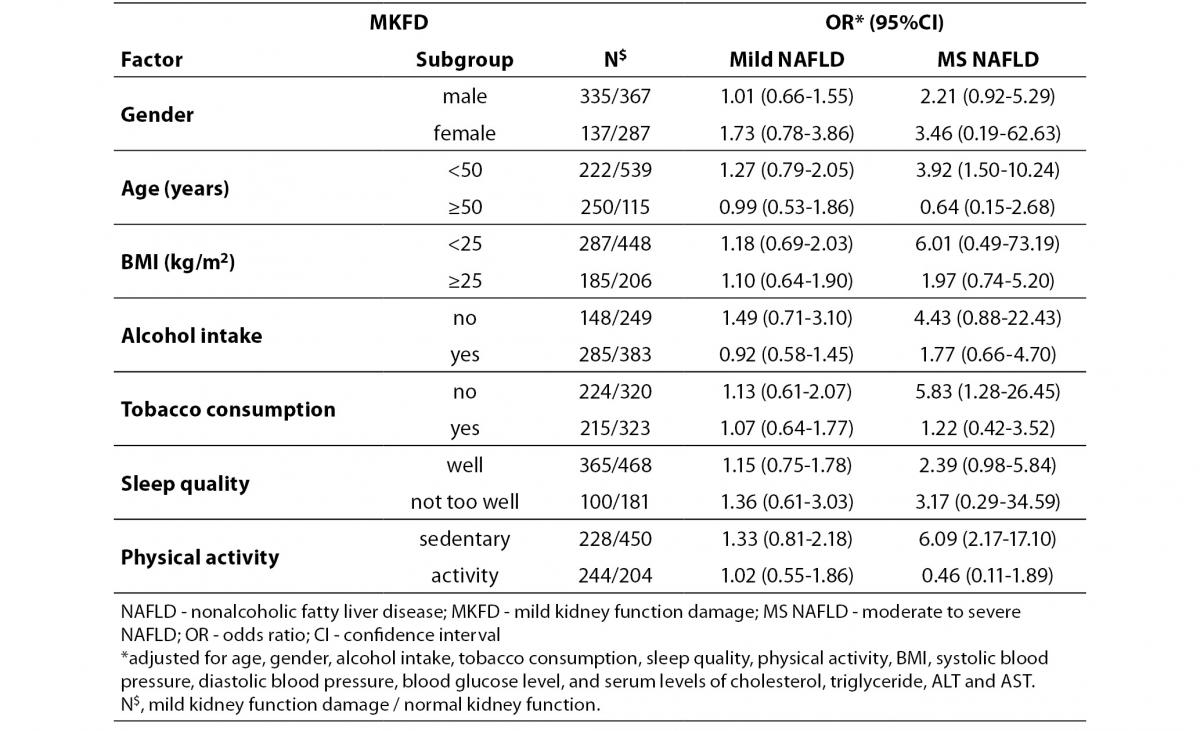

Table 3 showed MKFD risk associated with NAFLD stratified by different covariates respectively. All values were adjusted for gender, age, and other covariates. As illustrated by adjusted OR, the overall trend was that the higher risk of MKFD occurred in the more serious NAFLD. Especially, in the subgroups of age < 50 years (moderate to severe NAFLD versus normal liver OR = 3.92, 95% CI = 1.50-10.24), without tobacco consumption (moderate to severe NAFLD vs. normal liver OR = 5.83, 95% CI = 1.28-26.45) and sedentary (moderate to severe NAFLD vs. normal liver OR = 6.09, 95% CI = 2.17-17.10), moderate to severe NAFLD resulted in statistically significant increase of risk for MKFD (Table 3).

Table 3. MKFD associated with NAFLD levels stratified by gender, age, BMI, alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, sleep quality and average physical activity levels.

To evaluate the correlation of NAFLD with covariates, the levels of different covariates were compared among normal liver, mild NAFLD and moderate to severe NAFLD. Results showed that NAFLD could induce statistically significant changes in almost all covariates (Table 4). Intriguingly, significant differences of the covariates showed similar trends between MKFD versus normal kidney function and moderate to severe NAFLD, mild NAFLD versus normal liver (Tables 1 and 4).

Table 4. Comparison of different factors between subjects diagnosed as moderate to severe NAFLD, mild NAFLD versus normal liver

Discussion

Recently, it has been recognized that the growing prevalence of NAFLD imposes an increasing burden on kidney, and contributes to CKD in these population with or without diabetes mellitus (10,11,15). All these studies are based on the cut-off point of eGFR ≤ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or with overt proteinuria for CKD. However, according to the National Kidney Foundation Practice Guidelines (17,18), MKFD is more important than CKD in health care in that early detection and treatment of MKFD can prevent or delay the adverse outcomes of CKD. Therefore, aimed to explore the relationship between NAFLD and kidney function, we apply the cut-off point of eGFR < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 for MKFD.

This large population study showed that both mild NAFLD and moderate to severe NAFLD could significantly suppress eGFR, an index of kidney function. In particular, the negative association between eGFR and NAFLD was achieved from the subjects without diabetes, and the correlation coefficient did not substantially change with or without adjusted for blood glucose levels and other confounding factors. This finding is corroborated by the results from non-hypertensive and non-diabetic Korean men, illustrating an increased incidence of CKD in NAFLD subjects (15,16). It seems that NAFLD can suppress kidney function in a diabetes-independent manner. Intriguingly, some cross-sectional studies show NAFLD contributes to CKD development in type 1 and type 2 diabetes (10,11). Therefore, a logical explanation for these results from different population groups may be that both blood glucose and NAFLD are involved in impairing process of kidney function, while operating modes are independent.

Though accumulated evidences support the relationship between NAFLD and CKD (10-16), the underlying mechanisms linked NAFLD with CKD are still poorly understood. A plausibly speculative theory has been suggested that NAFLD and CKD share many important common risk factors and similar pathological processes (28). In consistence with the hypothesis, our results indicate that many covariates, including age, gender, sleep quality, physical activity, BMI, blood pressure, blood glucose, and serum concentration of total cholesterol, triacylglycerol, ALT and AST, show significantly similar changes between MKFD versus normal kidney function and NAFLD versus normal liver. However, whether NAFLD and CKD are merely coextensive consequences of these risk factors, or NAFLD is a direct risk factor contributing to the damage of kidney function, it is still an open question at present. This may deserve further investigation to carefully determine the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the pathogenesis of CKD and NAFLD from molecular, animal and other model systems.

In conclusion, this is the first study with specific goal for exploring the relationship between NAFLD and MKFD in population with normal blood glucose levels. The most striking finding of this study is that NAFLD is negatively associated with kidney function, indicated by eGFR, in nondiabetes population. The underlying mechanisms linked NAFLD with impaired kidney function may be common risk factors and similar pathological processes. The health care providers and the public should pay more attention to risk factor modifications to ameliorate NAFLD and improve kidney function.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Funds of China (30800207), National 863 Grants of China (2008AA02Z411), National Basic Research Program of China (2010CB530500, 2010CB530503), and Scientific Research Funds of Hunan Provincial Education Department.

Notes

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology 2004;40:1387-95.

2. Tominaga K, Kurata JH, Chen YK, Fujimoto E, Miyagawa S, Abe I, Kusano Y. Prevalence of fatty liver in Japanese children and relationship to obesity. An epidemiological ultrasonographic survey. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:2002-9.

3. Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1221-31.

4. Tiniakos DG, Vos MB, Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathology and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol 2010;5:145-71.

5. Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1341-50.

6. Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, Rodella S, Zoppini G, Pichiri I, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Hepatol 2010;53:713-8.

7. Ghouri N, Preiss D, Sattar N. Liver enzymes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and incident cardiovascular disease: a narrative review and clinical perspective of prospective data. Hepatology 2010;52:1156-61.

8. Kantartzis K, Thamer C, Peter A, Machann J, Schick F, Schraml C, et al. High cardiorespiratory fitness is an independent predictor of the reduction in liver fat during a lifestyle intervention in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2009;58:1281-8.

9. Harrison SA, Day CP. Benefits of lifestyle modification in NAFLD. Gut 2007;56:1760-9.

10. Targher G, Bertolini L, Chonchol M, Rodella S, Zoppini G, Lippi G, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease and retinopathy in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2010;53:1341-8.

11. Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, Zoppini G, Lippi G, Day C, Muggeo M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease and proliferative/laser-treated retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2008;51:444-50.

12. Targher G, Kendrick J, Smits G, Chonchol M. Relationship between serum gamma-glutamyltransferase and chronic kidney disease in the United States adult population. Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2006. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2010;20:583-90.

13. Yilmaz Y, Alahdab YO, Yonal O, Kurt R, Kedrah AE, Celikel CA, et al. Microalbuminuria in nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: association with liver fibrosis. Metabolism 2010;59:1327-30.

14. Yasui K, Sumida Y, Mori Y, Mitsuyoshi H, Minami M, Itoh Y, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and increased risk of chronic kidney disease. Metabolism 2011;60:735-9.

15. Chang Y, Ryu S, Sung E, Woo HY, Oh E, Cha K, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease predicts chronic kidney disease in nonhypertensive and nondiabetic Korean men. Metabolism 2008;57:569-76.

16. Ryu S, Chang Y, Kim DI, Kim WS, Suh BS. Gamma-glutamyltransferase as a predictor of chronic kidney disease in nonhypertensive and nondiabetic Korean men. Clin Chem 2007;53:71-7.

17. Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:137-47.

18. National-Kidney-Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39:S1-266.

19. Baskurt OK, Boynard M, Cokelet GC, Connes P, Cooke BM, Forconi S, et al. New guidelines for hemorheological laboratory techniques. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2009;42:75-97.

20. Chen K, Xie F, Liu S, Li G, Chen Y, Shi W, et al. Plasma reactive carbonyl species: Potential risk factor for hypertension. Free Radic Res 2011;45:568-74.

21. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian population and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157-63.

22. Liu S, Shi W, Li G, Jin B, Chen Y, Hu H, et al. Plasma reactive carbonyl species levels and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;26:1010-5.

23. Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998;15:539-53.

24. Zeng MD, Fan JG, Lu LG, Li YM, Chen CW, Wang BY, Mao YM. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases. J Dig Dis 2008;9:108-12.

25. Chan HL, de Silva HJ, Leung NW, Lim SG, Farrell GC. How should we manage patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in 2007? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:801-8.

26. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604-12.

27. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, eds. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley;2000.

28. Targher G, Chonchol M, Zoppini G, Abaterusso C, Bonora E. Risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Is there a link? J Hepatol 2011;54:1020-9.