Relationship between serum interleukin-1β levels and acute phase response proteins in patients with familial Mediterranean fever

Kadir Yildrim

[1]

Hulya Uzkeser

[*]

[1]

Mustafa Keles

[2]

Saliha Karatay

[1]

Ahmet Kiziltunc

[3]

Muhammet Dursun Kaya

[4]

Abdulkadir Yildirim

[3]

Introduction

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is a group of inherited inflammatory disorders that are characterized by recurrent episodes of fever accompanied by arthritis, peritonitis, pleuritis, erysipelas like erythema and seen dominantly in Mediterranean populations (1). Mutations in MEFV gene, which encodes pyrin, a protein that regulates the inflammatory process in immune cells, were reported as cause of FMF disease in 1997 (2,3). The traditional clinical view of the disease includes repeated acute short-lived febrile and painful attacks with variable periods of remission. The patients with FMF have an increased acute phase response during these attacks and usually this increase returns to normal in attack-free periods. Recent studies have demonstrated that subclinical inflammation may continue during attack-free periods in approximately 30% of FMF patients (4-6). The acute phase response of inflammationinvolves the increasein serum level of liver-derived proteins (7). These proteins have diverse functions in the inflammatoryprocess. Inflammation accompanied by a marked acute phase response such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloid A (SAA) and fibrinogen also plays an important function in the initiation and progression of FMF (5). Also, some researchers use to SAA protein levels as an important marker of chronic inflammation in between attacks of FMF (6). Colchicine therapy commonly keeps from the attacks and related inflammation (8).

The cytokines that are produced throughout and took part in inflammatory procedure are the principal stimulators of the manufacture of acute phase proteins (9). Some cytokines and their receptors have been studied in patients with remission and attack periods of FMF disease. The serum levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) have been shown to be higher in patients at the attack periods than remission periods and control groups (10-13). IL–1β levels are increased in the blood of patients with a multiplicity of infectious, immune, or traumatic situations and play a fundamental role in inflammation (9). ESR is a comparatively nonspecific test that is regularly ordered during the diagnosis and scanning of inflammatory diseases. CRP increase is a part of the acute phase response at acute and chronic inflammation. It is mainly produced in the liver and released in six hours with increased amounts when acute inflammatory stimulus began (14). Fibrinogen, a protein that is made in the liver excessively, is vital for the blood clotting process. A number of studies have been reported activated cytokine network during attacks of FMF. However, cytokine activity is not known clearly in FMF during attack-free period. Especially, there has been no adequate study investigating serum IL–1β levels in patients with FMF in between attacks. Therefore, present study was performed to determine IL–1β, ESR, CRP and fibrinogen concentration as indicators of inflammation status and the relationship among these parameters in patients with FMF during attack-free period.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This study was conducted during in the period from 2009 to 2010 at the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Outpatients Clinics. This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee. All the participants were informed of the study protocol and their written informed consents, according to the Declaration of Helsinki, were obtained.

In the present study groups comprised 35 FMF patients in attack-free period (male gender, N (ratio): 10 (0.29)), and 25 age and sex matched healthy controls (male gender, N (ratio): 9 (0.36)). The subjects aged 18-60 years were recruited in the study.

Thirty five patients who fulfilled clinical diagnostic criteria for FMF (15) were consecutively included in the study. Attack-free periods were defined as being free of attacks for at least 3 weeks. All of the patients were receiving regular colchicine treatment during study (1-1.5 mg/day).

Control subjects were healthy subjects without a history of inflammatory or general disease. A detailed medical history was taken and clinical examinations were performed on all participants. The healthy subjects and patients were not habituated to smoking and/or alcohol consumption. Patients with liver and kidney diseases, diabetes, peripheral neuropathy, familial hypercholesterolemia, thyroid and parathyroid diseases, hematological, lymphoproliferative and other malignant diseases were excluded after this status was self-declared by the individuals. Aforementioned disease statuses were also controlled from their medical records.

Methods

All blood samples were obtained at attack-free periods and stored at -80 °C until analysis during one year. Fasting serum samples were collected during morning hours to avoid diurnal variations.

Laboratory parameters included IL-1β, ESR, CRP and fibrinogen. Serum IL-1β levels were measured with commercial (Cat. No: KAP 1211, Biosource, Belgium) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits. The intra-assay and interassay coefficient of variation percentages were declared by the manufacturer as 4.4% and 6.7% respectively.

ESR and CRP were determined in whole blood and serum aliquots, respectively. ESR was determined according to the Westergren method and CRP by a nephelometric method (Beckman Array Protein System, California, USA). Plasma fibrinogen levels were determined using commercial kits (Lot. No: 104470, STA-FIB, France) by STA compact autoanalyzer (STA, France).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (SPSS, version 15.0). Differences between groups were tested using the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlation analysis between the parameters was performed by Pearson’s correlation test. The results were presented as median and interquartile range (Q1-Q3). A P value below 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

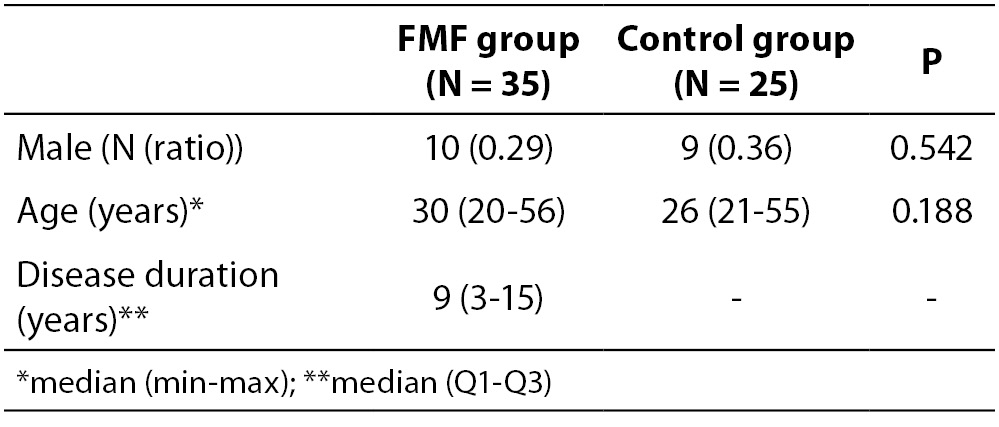

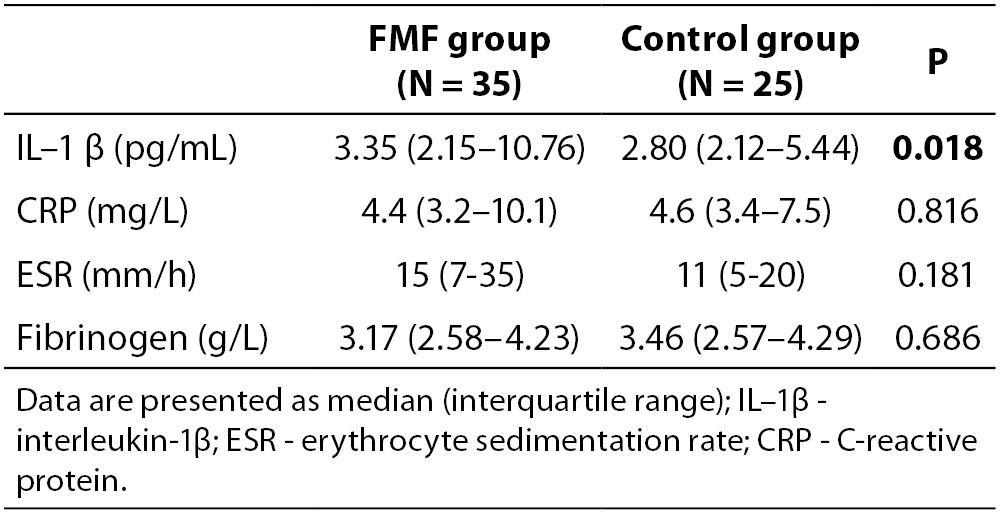

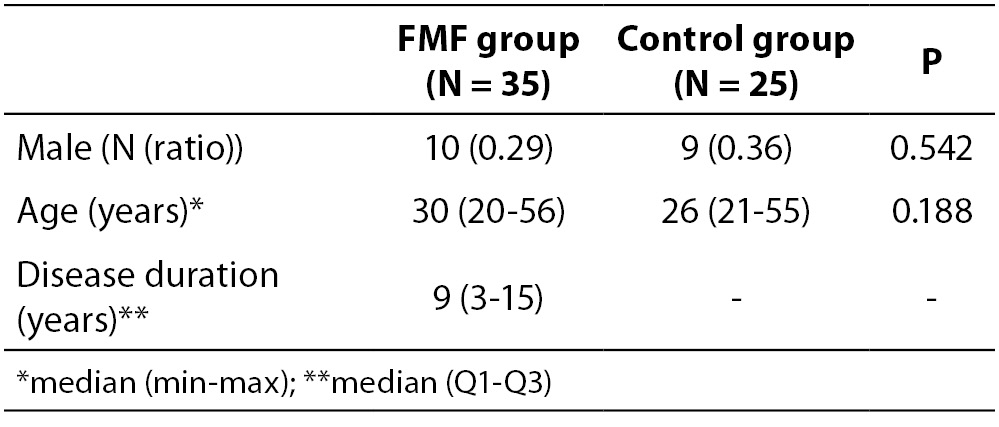

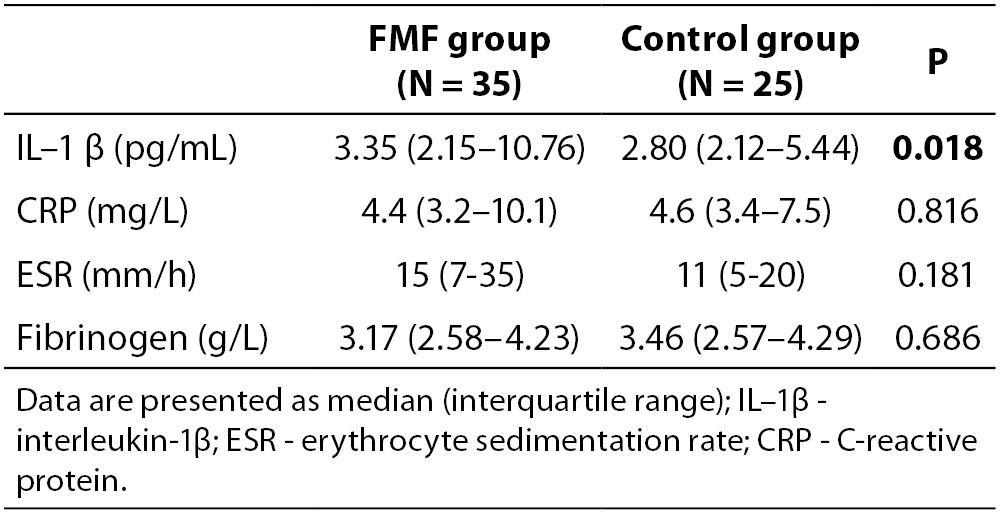

The demographic and clinical characteristics of 35 FMF patients and 25 volunteer control subjects are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to demographic data. Table 2 summarizes laboratory findings such as IL-1β, ESR, CRP and fibrinogen levels in the study population and control groups. The serum levels of IL-1β in attack-free patients with FMF were significantly higher than in the healthy controls (P = 0.018), but not other parameters of inflammation, including ESR, CRP and fibrinogen (P = 0.181, P = 0.816, P = 0.686, respectively).

Table 1. The demographic and clinical features of the patients with FMF and healthy controls.

Table 2. The laboratory features of the patients with FMF and healthy controls.

There was a positive correlation between serum IL-1β and CRP (r = 0.513, P = 0.002), in patients with FMF. However, there were no correlations between IL-1β and ESR and fibrinogen.

Discussion

FMF is an autosomal recessive disorder that characterized by the exacerbations and remissions (16). Duration and frequency are not presumable. Its clinical course is characterized by recurrent self-limited attacks of fever and polyserositis at irregular intervals, accompanied with an increase in acute phase reactants (1,2).

Acute phase proteins, whose synthesis is altered during inflammation, injury and infections, are probably affected by interleukins, released from the site of injury or inflammation (17). These acute phase proteins comprise ESR, CRP, fibrinogen, SAA and alpha 1-acid glycoprotein. The major inducers of acute phase proteins are IL–1α (18)., IL–6, and TNF-α (18).

Attacks of FMF are accompanied by an intense inflammatory response (9). In literature, elevated plasma concentration of acute phase reactants like ESR, CRP and fibrinogen and elevated serum cytokines levels such as IL-1β have been determined during the attack periods (13,19). However, there is still no adequate study investigating serum IL-1β values in FMF patients with attack-free period. Notarnicola et al. (20) have investigated TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 cytokine expression at the transcriptional level. They have reported that these parameters were more elevated in attack-free FMF patients than in controls. In our study, serum IL-1β levels are significantly higher the attack-free period of FMF than the controls. In contrast to our and Notarnicola’s studies, Gang et al. showed that levels of IL-1β were not elevated in FMF patients during attacks or attack-free periods (18). The difference between results may be due to the determination time of FMF phase, age group of patients and processes and method of IL-1β determination. On the other hand, some biological variations of the components such as cytokines in biological fluids of the human body have been reported (21). The conflict results on serum IL-1β levels may also due to inter-individual and intra-individual biological variation. However, these findings still suggest a continuing pro-inflammatory state and subclinical inflammation in attack-free period of patients with FMF receiving regular colchicine drug (19-22).

In the present study, ESR, CRP and fibrinogen levels were not significantly different in patients with FMF at attack-free period when compared to healthy control group. Similar findings have been established by other recent studies. In a previous study CRP levels of attack free- FMF patient were higher than healthy control groups (5). In our study, CRP levels of FMF patient were not significantly higher than healthy controls. However, only five patients were over the normal range.

In the literature, it was reported that approximately 30% of FMF patients have a chronic subclinical inflammation with elevated acute phase reactants during attack free periods (6). These contradictory results of different studies may be due to different inflammation phase in patients with attack free period.

Although our study had some limitations such as the small number of patients,our results suggest that the elevation of IL-1β levels may be important in monitoring subclinical inflammation of attack free period in FMF patients. Further studies are needed to define the relationship between IL-1β values and inflammation in a large group of patients.

Notes

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Drenth J, Van der Meer J. Hereditary periodic fever. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1748-56.

2. The French FMF Consortium. A candidate gene for familial Mediterranean fever. Nat Genet 1997;17:25-31.

3. Livneh A, Langevitz P. Diagnostic and treatment concerns in familial Mediterranean fever. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2000;14:477-98.

4. Orbach H, Ben-Chetrit E. Familial Mediterranean fever - a review and update. Minerva Med 2001;92:421-30.

5. Korkmaz C, Ozdogan H, Kasapcopur O, Yazıcı H. Acute phase response in familial Mediterranean fever. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:79-81.

6. Ben-Zvi I, Livneh A. Chronic inflammation in FMF: markers, risk factors, outcomes and therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011;7:105-12.

7. Keles M, Eyerci N, Uyanik A, Aydinli B, Sahin GZ, Cetinkaya R, et al. The frequency of familial Mediterranean fever related amyloidosis in renal waiting list for transplantation. EAJM 2010;42:19-20.

8. Chae JJ, Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Advances in the understanding of familial Mediterranean fever and possibilities for targeted therapy. Br J Haematol 2009;146:467-78.

9. Sims JE, Smith DE. The IL-1 family: regulators of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2010;10:89-102.

10. Baykal Y, Saglam K, Yilmaz MI, Taslipinar A, Akinci SB, Inal A. Serum sIL-2r, IL–6, IL–10 and TNF-alpha level in familial Mediterranean fever patients. Clin Rheumatol 2003;22:99-101.

11. Erken E, Gunesacar R, Ozbek S, Konca K. Serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels in familial Mediterranean fever. Ann Rheum Dis 1996;55:852-5.

12. Oktem S, Yavuzsen TU, Sengul B, Akhunlar H, Akar S, Tunca M. Levels of interleukin–6 (IL–6) and its soluble receptor (sIL-6R) in familial Mediterranean fever patients and their first degree relatives. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2004;22:34-6.

13. Direskeneli H, Ozdogan H, Korkmaz C, Akoglu T, Yazici H. Serum soluble intercellular adhesion molecule–1 and interleukin-8 levels in familial Mediterranean fever. J Rheumatol 1999;26:1983-6.

14. Marnell L, Mold C, Du Clos TW. C-reactive protein: ligands, receptors and role in inflammation. Clin Immunol 2005;117:104-11.

15. Livneh A, Langevitz P, Zemer D, Zaks N, Kees S, Lidar T, et al Criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1879-85.

16. Yildirim K, Uzkeser H, Uyanik A, Karatay S, Kiziltunc A. Trace element levels in patients with familial Mediterranean fever. EAJM 2011;43:79-82.

17. Borghetti P, Saleri R, Mocchegiani E, Corradi A, Martelli P. Infection, immunity and the neuroendocrine response. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2009;130:141-62.

18. Gang N, Drenth JP, Langevitz P, Zemer D, Brezniak N, Pras M, et al. Activation of the cytokine network in familial Mediterranean fever. J Rheumatol 1999;26:890-7.

19. Poland DC, Drenth JP, Rabinovitz E, Livneh A, Bijzet J, van het Hof B, et al. Specific glycosylation of alpha(1)-acid glycoprotein characterises patients with familial Mediterranean fever and obligatory carriers of MEFV. Ann Rheum Dis2001;60:777-80.

20. Notamicola C, Didelot M.N, Seguret F, Demaille J, Touitou I. Enhanced cytokine mRNA levels in attack- free patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Genes Immun 2002;3:43-5.

21. Ricós C, Perich C, Minchinela J, Álvarez V, Simón M, Biosca C, et al. Application of biological variation – a review. Biochem Med 2009;19:250-9.

22. Düzova A, Bakkaloglu A, Beşbaş N, Topaloğlu R, Özen S, Özaltın F, et al. Role of A-SAA in monitoring subclinical inflammation and in colchicines dosage in familial Mediterranean fever. Clin Exp Rheum 2003;21:509-14.