Introduction

Fifty years ago, some researchers first reported that collection of blood gas samples into the syringe with liquid heparin caused dilutional error (1-3). But, heparinized blood collection for blood gas analysis in some clinics or hospitals is still preferred in plastic syringes with liquid heparin instead of syringes with dry heparin due to economical and traditional reasons.

Some researchers notified recommendations about standardized blood collection into syringes washed with liquid heparin (4,5). Also, International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) recommended for blood gas sampling to fill dead space of the syringe with heparin, to lubricate the inner wall of the syringe, to expel the excess anticoagulant and to collect the least 20 times the dead space volume of blood (6). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC) published the guidelines for blood gas analysis which were not described the blood collecting procedure in syringes washed with liquid heparin, but they warned the combine effects from together dilutional and chemical effects of liquid heparin to blood gas tests (7,8).

Despite all these publications, we have frequently observed the nonstandardized blood gas sampling with liquid heparin (especially using different volumes syringes, different sizes needles and collecting different sample volume) is used for patient’s comfort, easier application or ignorance about the effects. For these reasons, in this study, we evaluated the effect of i) dilution rates of disposable plastic syringes and needles; ii) final heparin concentrations; and iii) non-standardized sampling volume on blood gas parameters sampled in syringes of various sampling capacity, washed with heparin.

Materials and methods

Materials

Four different volumes of disposable plastic syringes (1, 2, 5 and 10 mL) (Hayat Medical Device Inc, Istanbul, Turkey) and five different sizes of disposable needles (Gauge: diameter x length, 20G: 0.90 x 38 mm, 21G: 0.80 x 38 mm, 22G: 0.70 x 32 mm, 25G: 0.50 x 26 mm, 26G: 0.45 x 13 mm) (Hayat Medical Device Inc, Istanbul, Turkey) which are frequently found and used in clinics or hospitals, were used in this study. Syringes and needles were weighed with “Precisa XB 220A” precision balance (Precisa Gravimetrics AG, Dietikon, Switzerland) which has a capacity of 320 g, a readability of 0.0001 g, a repeatability of 0.1 g, a linearity of 0.2 g and an auto calibration facility. Syringes were washed by “Nevparin flakon” sodium heparin solution (Mustafa Nevzat İlaç Sanayi AŞ, İstanbul, Turkey) which contains 5000 IU/mL heparin.

After the approval of the Ethical Comittee (Dokuz Eylul University Medical Faculty, Izmir, Turkey), the informed consent was obtained and samples were taken from seven healthy volunteers. Blood samples were collected by venous puncture into previously heparinized 50 mL-syringes (Hayat Medical Device Inc, Istanbul, Turkey). The heparinized syringes containing approximately 10 IU/mL heparin were prepared via injection 0.10 mL of 5000 IU/mL sodium heparin solution in 1 mL-syringe from the open end of 50 mL-syringes.

The blood gas [pH, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2), partial pressure of oxygen (pO2)] and electrolytes [sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), ionized calcium (iCa2+), ionized magnesium (iMg2+)] parameters were analyzed by two identical analyzers Nova Critical Care Xpress (Nova Biomedical Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. On-board tri-level auto QC packs (PN 35625-30, Nova Biomedical Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) were automatically analyzed 3 times a day for quality control on the Nova system.

Study design

This multi-step experimental study was performed between June and August 2011 in the Central Laboratory of Dokuz Eylül University Hospital (Izmir, Turkey).

Step 1: Determining the effect of syringe volume and needle size on percent dilution ratios (PDRs) and final heparin concentrations (FHCs):

The PDRs and FHCs in different volumes syringes and different sizes needles were calculated from the dead space and total capacity for each material. Different volumes disposable plastic syringes with attached needles (1, 2, 5 and 10 mL) and different sizes needles with attached tips (20, 21, 22, 25 and 26G) were weighed 10 times. For suctioning and dispensing pure water, the needles were combined with 1 mL-syringes. Then, the needles were weighed without syringes. The balance was zeroed before each measurement. The measurements and calculations performed are described below.

Descriptions of weights:

- Empty weight; newly unpacked empty syringes attached with needles and needles attached with tips were weighed.

- Full-filled weight; syringes and needles which were filled with pure water to total capacity were weighed.

- Washed weight; syringes were weighed after applying standardized washing with pure water. For standardized washing, syringes were washed consecutively 2 times by filling to total capacity graduation lines and then emptying to zero graduation lines with pure water.

Descriptions of calculations:

- Dead space (DS); is the remaining amount of pure water in syringes which were filled with pure water and then emptied, in needles which were only filled with pure water, it was calculated via formula below:

- For syringes; Weight of dead space (g) = Washed weight (g) - Empty weight (g);

- For needles; Weight of dead space (g) = Full-filled weight (g) - Empty weight (g);

- Volume of dead space (mL) = Mass of dead space (g) x Z factor (mL/g). Z factor is a correction factor in the volumetric calculations to compensate for the density of the water at the test conditions. To find the Z factor, Z factor chart were used according to temperature (on row) and barometric pressure (on column) measured during the test (9).

- Total capacity (TC); is the amount of suctioned pure water into syringes, it was calculated via formula below:

- Weight of total capacity (g) = Full-filled weight (g) – Empty weight (g);

- oVolume of total capacity (mL) = Mass of total capacity (g) x Z factor (mL/g).

- Percent dilution ratio (PDR); is the percent ratio of liquid volumes retain in dead space of syringes or needles to volumes of total capacity of syringes, is the amount of dilution error, it was calculated via formula below:

- Percent dilution ratio (%) = (Volume of dead space (mL) / Volume of total capacity (mL)) x 100.

- Final heparin concentration (FHC); is the amount of heparin in sample which suctioned to syringes washed with liquid heparin, is the amount of chemical error, it was calculated via formula below:

- Final heparin concentration (IU/mL) = (Heparin volume (mL) / Volume of total capacity (mL)) x Heparin concentration used (5000 IU/mL). Heparin volume is an amount of the remaining heparin volume in dead volume of syringes. Volume of total capacity is the amount of suctioned pure water or sample volume into syringes.

- Percent of total dead space (PTDS): is the percent ratio of dead space of needles to total dead space of syringes. It was calculated using formula below:

- Percent total dead space (PTDS) (%) = (Volume of dead space of needle (mL) / Volume of total dead space of syringe (mL)) x 100.

Step 2: Determining the effect of sample volume size on PDRs and FHCs:

After all syringes were washed, 0.5 mL and 1 mL of pure water were suctioned into 1 mL- syringes; 0.5 mL, 1 mL and 2 mL into 2 mL- syringes; 0.5 mL, 1 mL, 2 mL and 5 mL into 5 mL- syringes; 0.5 mL, 1 mL, 2 mL, 5 mL and 10 mL into 10 mL- syringes for determining the effect of nonstandardized sampling size that is less than the full volume sampling on dilutional and chemical error. Filled and emptied syringes with attached needles were weighed. Total capacities of syringes, PDRs and FHCs in syringes were calculated.

Step 3: Determining the effect of different PDRs and FHCs on blood gas and electrolyte parameters:

50 mL venous blood samples in previously heparinized syringes were obtained from 7 volunteers. Whole blood samples obtained from each volunteer were suctioned into 10 mL-syringes previously washed with liquid heparin, in volumes of 0.5 mL, 1 mL, 2 mL, 5 mL and 10 mL. Because of all samples analysis finished in > 30 minutes, the samples (50-mL whole blood and 10-mL experimental aliquots) were kept on ice until the analysis and the samples were remixed by inverting and rolling horizontally before analysis. Baseline whole blood sample aliquots suctioned into empty syringes with no additive and no washed were analyzed for comparison before each set. The error of baseline samples which have approximately 10 IU/mL of FHC (and 0.2% of PDR) was neglected. Each aliquot set was analyzed for blood gas parameters as soon as possible within themselves (within 5-10 minutes). Then, the changes and the percent changes from baseline were calculated for each parameter. They were calculated via formula below:

- Change in test result = Experiment sample test result - Baseline sample test result.

- Percent change in test result (%) = (Change in test result / Baseline sample test result) x 100.

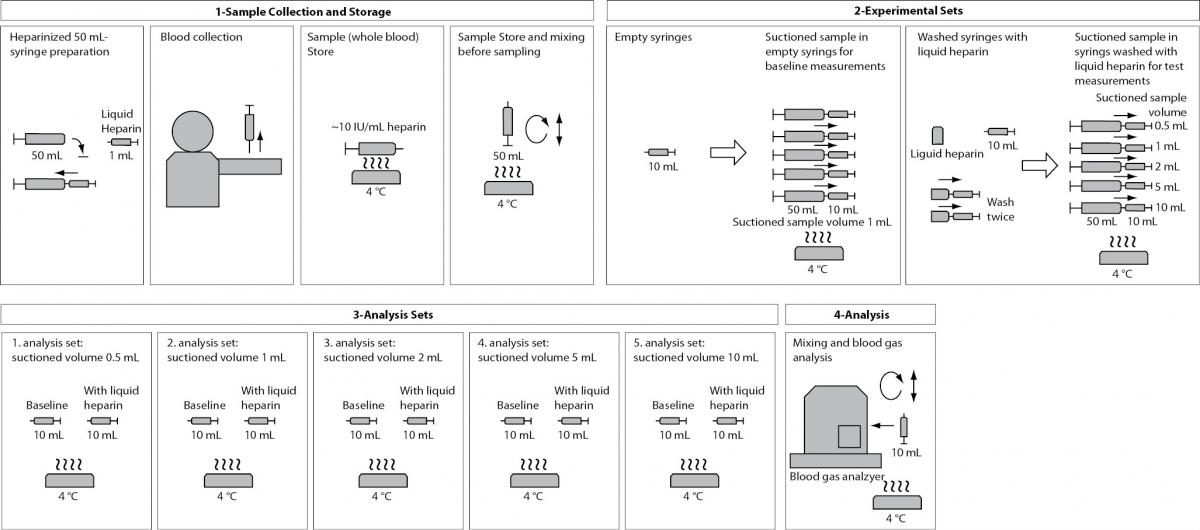

These steps are presented in a flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the Step 3.

Step 4: Determining the erroneous results due to the nonstandardized sampling size in random clinical samples according to the German Medical Association Directive on Quality Assurance of Quantitative Laboratory Tests for Medical Purposes (RiliBAK)’s Allowable Total Error (TEa):

According to six-month data, on average 3109 blood gas samples per month are analyzed on two blood gas devices in Central Laboratory of Dokuz Eylul University Hospital. The samples which have < 0.5 mL for 10 mL-syringes and < 0.2 mL for other syringes of sampling size are rejected because of blood gas device warns “no sample error” alarm. The distribution of samples according to sampling size were determined from the consecutive 100-routine blood gas samples at working hours in last 2 days to our laboratory. Then the bias (%) of routine blood gas results according to PDRs and FHCs from nonstandardized sampling size were compared according to the RiliBAK’s TEa. The total allowable limits of RiliBAK are 0.06 for pH, 12% for pCO2, 12% for pO2, 5% for Na+, 9.1% for K+, 15% for Ca2+ (10).

Analytical validation of experimental methodology

Gravimetric measurements

To validate the methodology in experimental methods used in this study, 0.1 mL and 1 mL of pure water were suctioned by calibrated micropipettes and then weighed 20 times. Micropipets were calibrated with a different precision balance by a commercial calibration laboratory (Omega Kalibrasyon Merkezi, İzmir, Turkey) which is accredited according to ISO/EIC 17025 by Turkish Accreditation Agency (TURKAK). Then CV% ((SD/Mean) x 100), bias% ([(Measured value – True value) / True value] x 100) and total error (Bias% + (1.65 x CV%)) were calculated. CV% were 0.81% and 0.16%, bias% were 0.60% and 0.30%, total error were 2.19% and 0.58% for 0.1 mL and 1 mL volumes, respectively.

The same measurements were repeated by using heparin. Then densities of water and heparin were calculated as 0.995 g/mL and 1.025 g/mL for 1 mL volumes, respectively. The density difference between heparin and pure water was calculated as 3.1%. Considering that this difference in density is too small to cause any difference in attachment to inner surface of syringes and needles between heparin and water, thus pure water was used instead of heparin for dead space determination.

Blood gas measurements

The pH, pCO2, Na+, K+, iCa2+, iMg2+ were measured by ion selective electrode potentiometry, and pO2 was measured by amperometry on blood gas analyzer. The method validations of tests done according to the requirements of the ISO 15189:2007 (11). Coefficient variation (CV) (%) and bias (%) of tests were determined, and then total errors (TE) of tests were calculated by “TE = bias (%) + 1.65 CV (%)” formula. Tests were validated, if total errors of tests were lower than the RiliBAK TEa (10).

Statistical analysis

The distribution of the variables was determined using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In normally distributed groups the results were presented with mean and SD. The significance of the changes in blood gas and electrolyte parameters at different PDRs and FHCs compared with PDRs and FHCs of full-filled syringes were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using PASW Statistics or Windows 18.0 (IBM Corporation, NY, US). Post hoc analysis was performed by Bonferroni posthoc test because of testing the complex pairs and reducing the probability of a Type I error (12). P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The effect of syringe volume and needle size on PDRs and FHCs

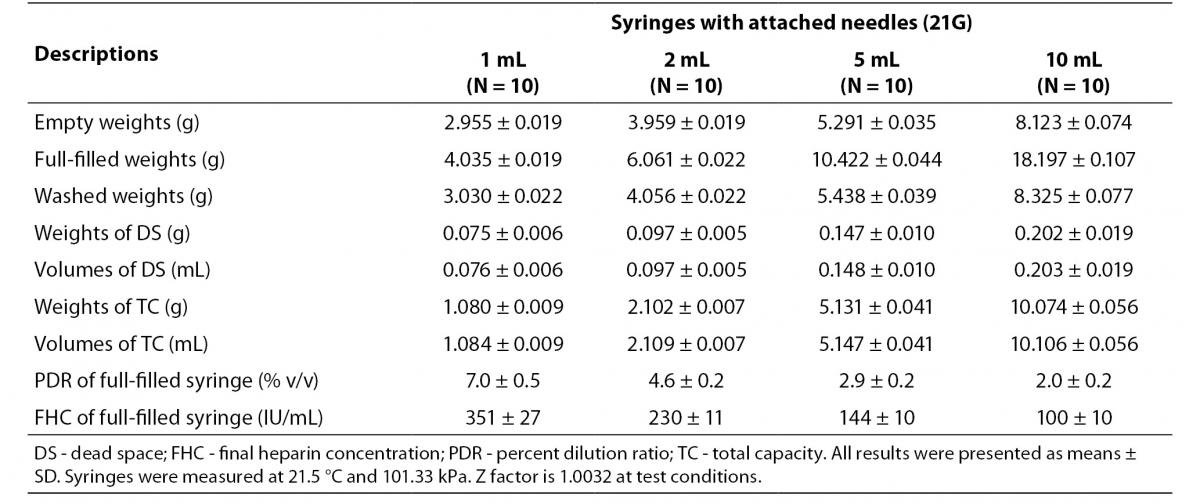

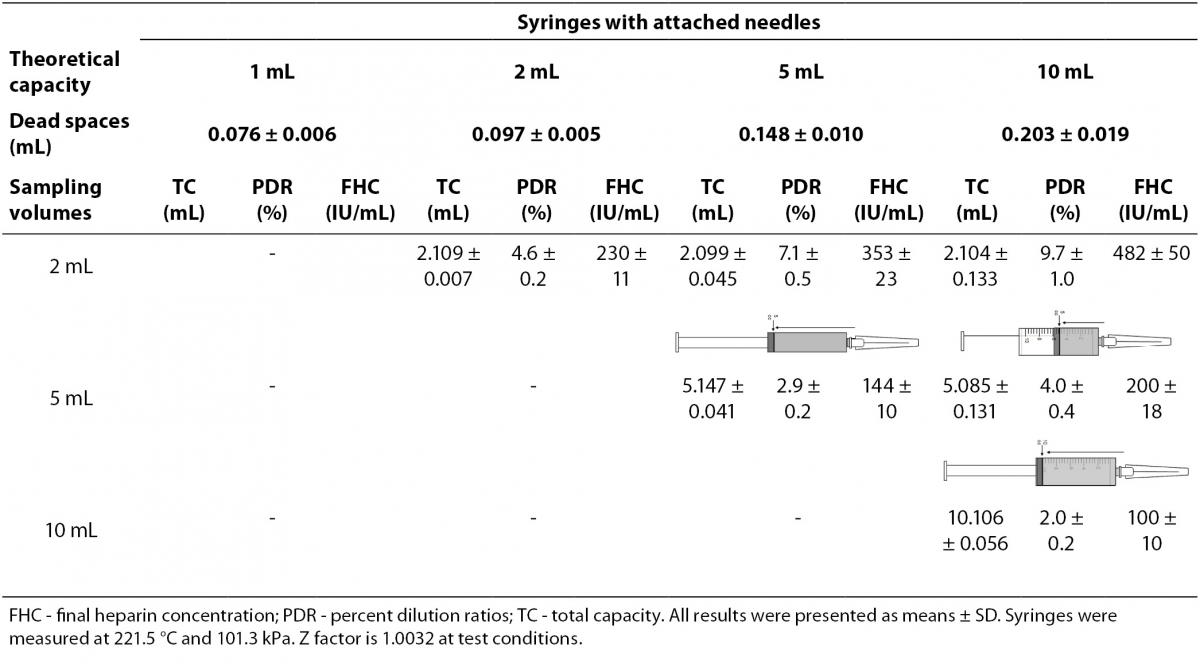

The dead spaces were determined as 0.203 mL in 10 mL-, 0.148 mL in 5 mL-, 0.097 mL in 2 mL-, 0.076 mL in 1 mL-syringes. We determined PDRs and FHCs of 1 mL, 2 mL, 5 mL, 10 mL volumes syringes were 7.0%, 4.6%, 2.9%, 2.0% and 351 IU/mL, 230 IU/mL, 144 IU/mL, 100 IU/mL, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. The percent dilution ratios and final heparin concentrations from different volumes syringes with attached needles.

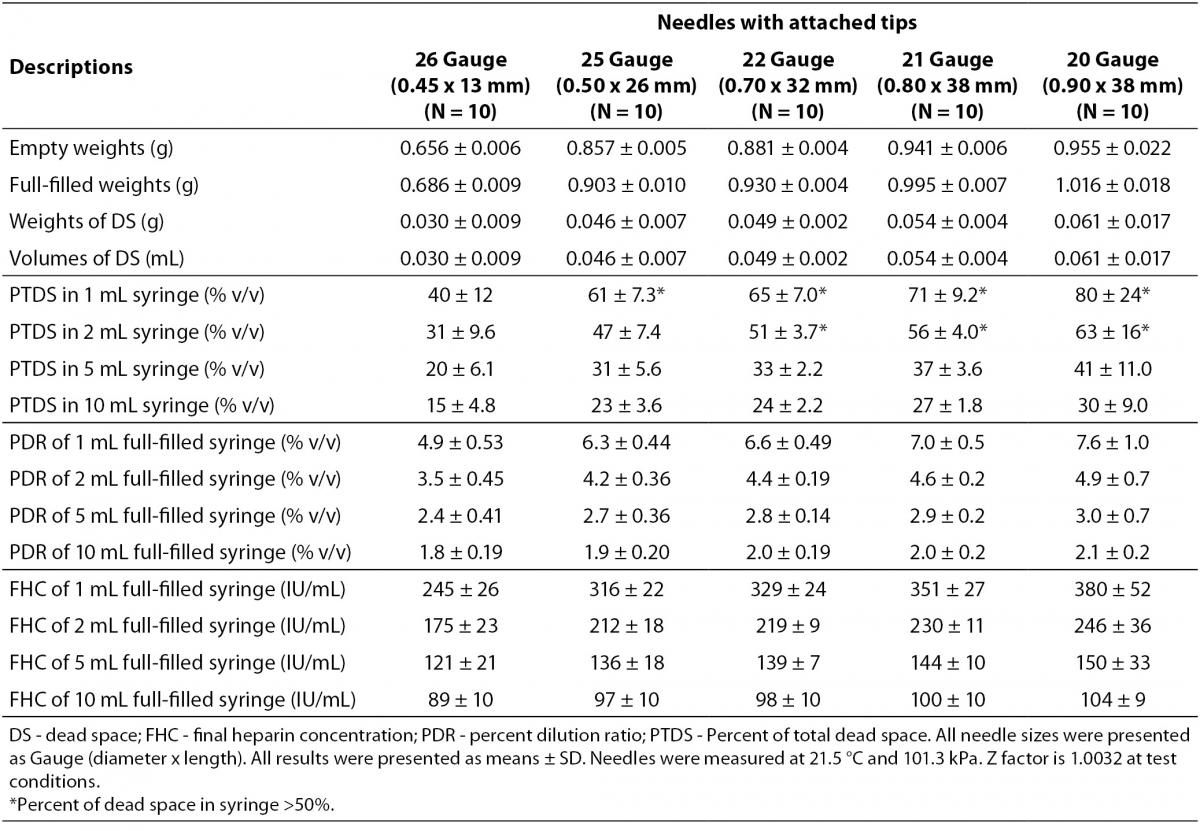

The dead spaces were determined as 0.061 mL in 20G-, 0.054 mL in 21G-, 0.049 mL in 22G-, 0.046 mL in 25G-, 0.026 mL in 26G-needles. The dead spaces of 20G-, 21G-, 22G-, 25G- needles for 1 mL-syringe and 20G-, 21G-, 22G-needles for 2 mL-syringe were determined to consist more than 50% of total dead volume. The PDRs and FHCs of different sizes needles with attached tips were shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The dead spaces, percent dilution ratios and final heparin concentrations in different sizes needles.

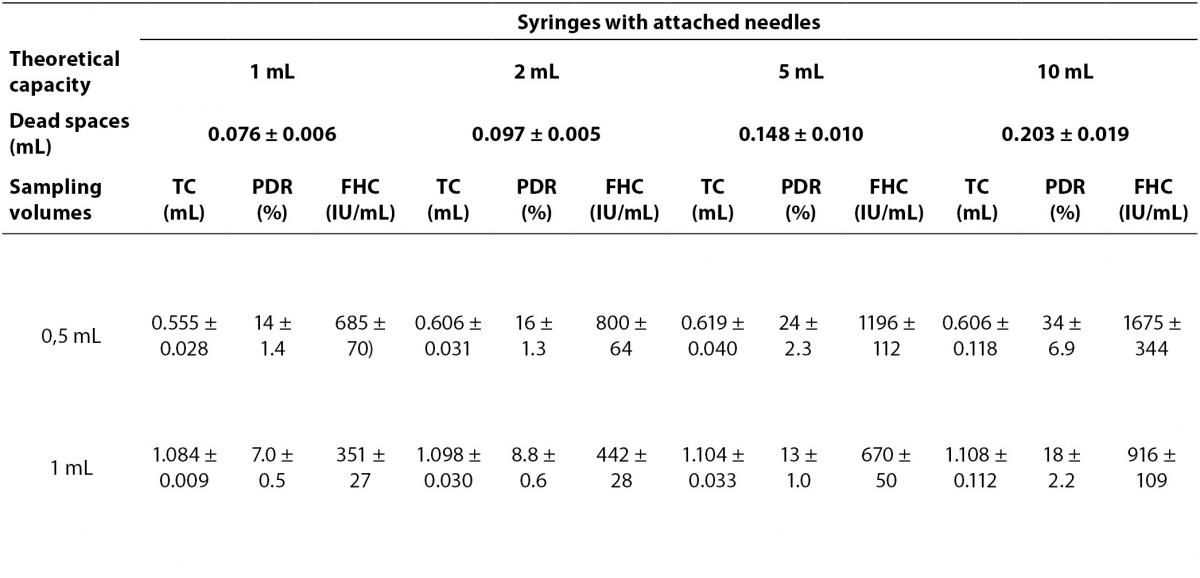

The effect of sample volume size on PDRs and FHCs

The PDRs and FHCs from different sample volume size are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. The percent dilution ratios and final heparin concentrations from different sample volume size in different syringes.

The effect of different PDRs and FHCs on blood gas and electrolyte parameters

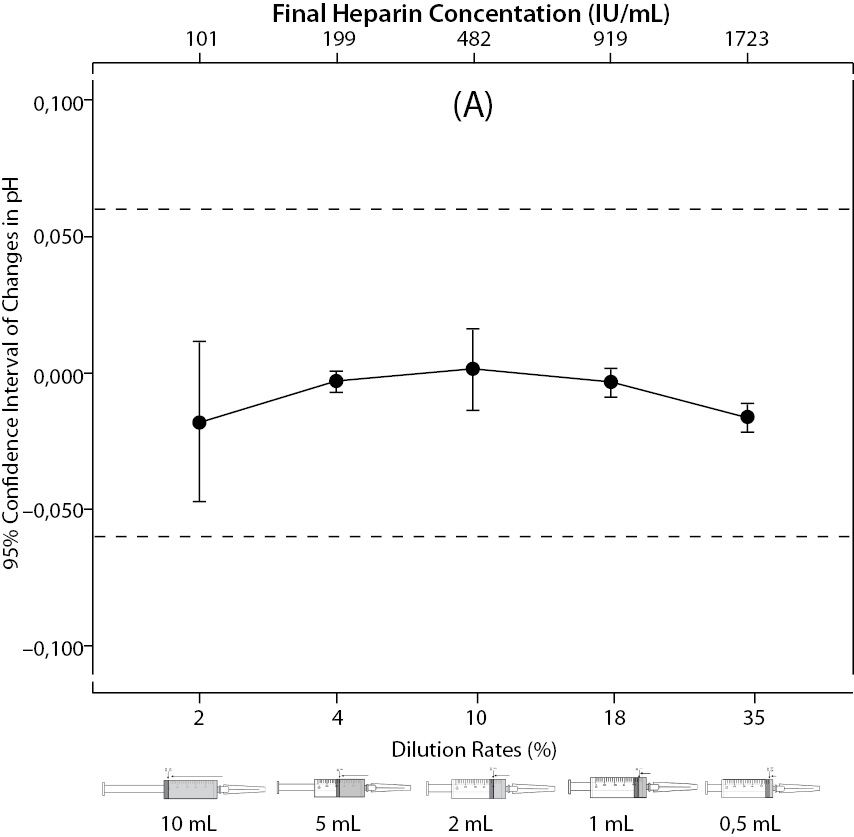

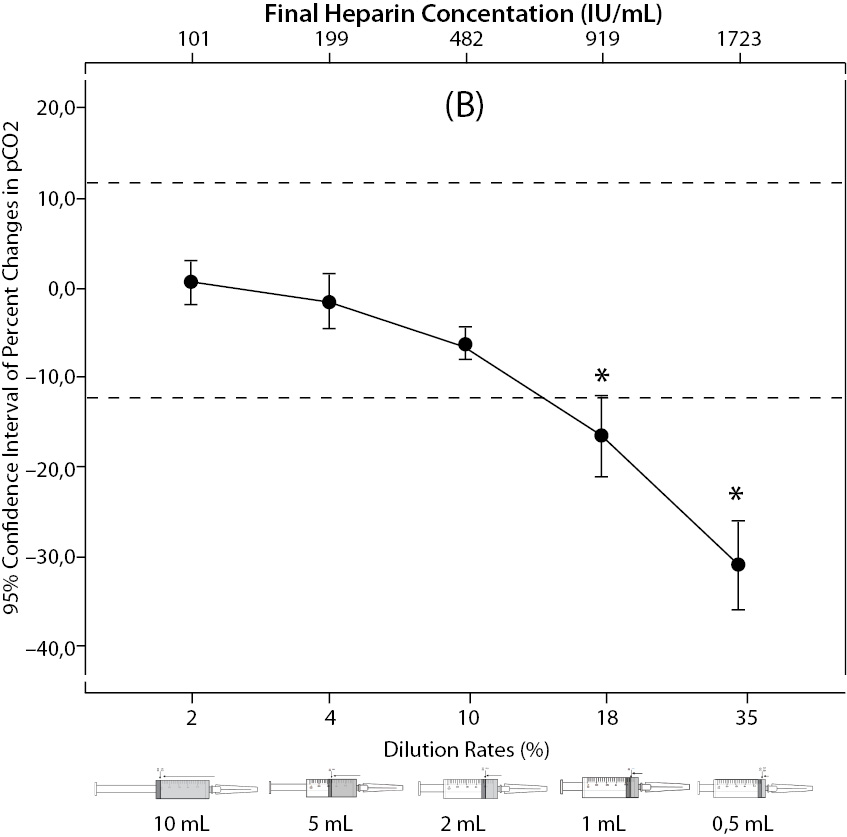

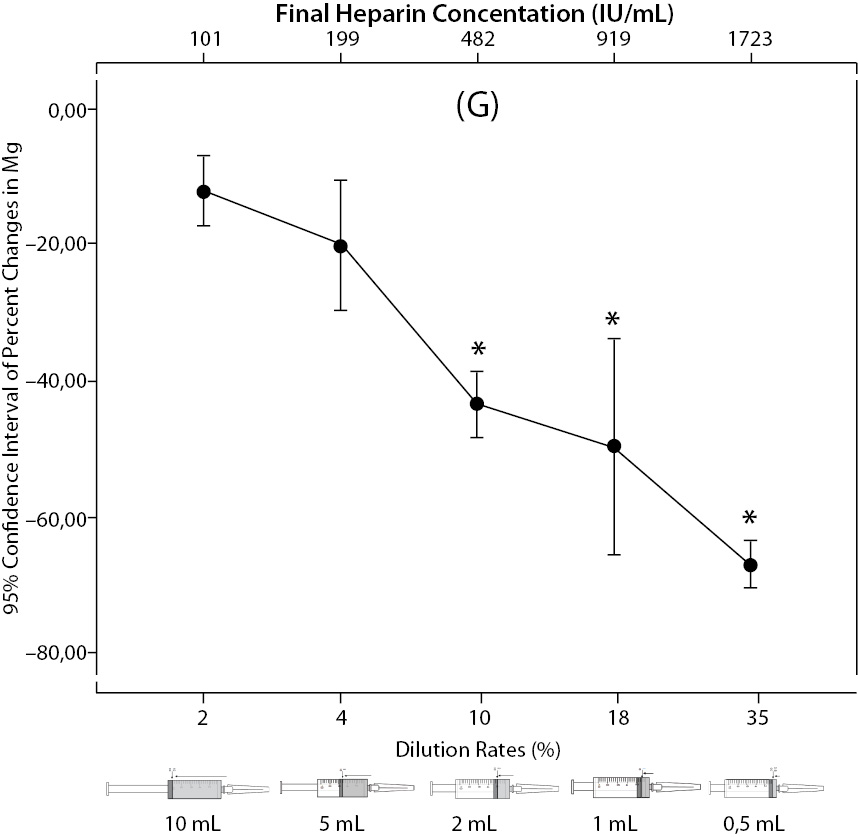

There was no statistical difference in changes of pH (P = 0.128); but the percent changes of pO2, pCO2, Na+, K+, iCa2+, iMg2+ were significantly different between all groups (P < 0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that samples in full-filled syringes were significantly different than 2 mL, 1 mL, 0.5 mL sample volume for all parameters (P < 0.019, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 for Na+;P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 for K+;P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 for iCa2+; P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 for iMg2+, respectively) except pCO2, pO2 which were significant in 1 and 0.5 mL sample volume (P < 0.001, P < 0.001 for pCO2, and P = 0.010, P < 0.001 for pO2, respectively).

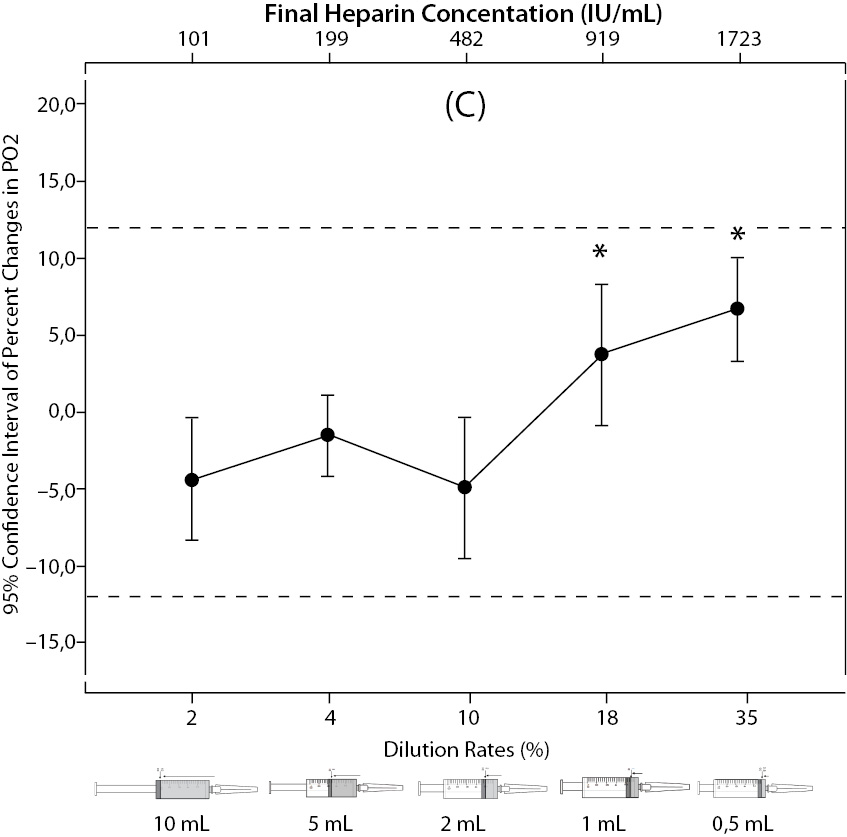

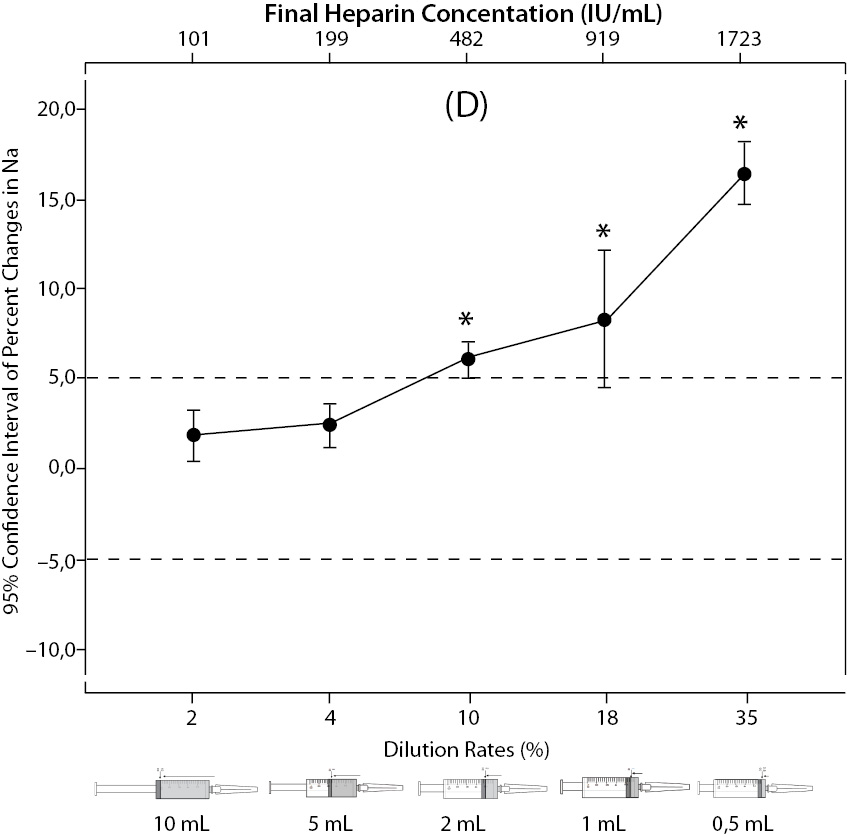

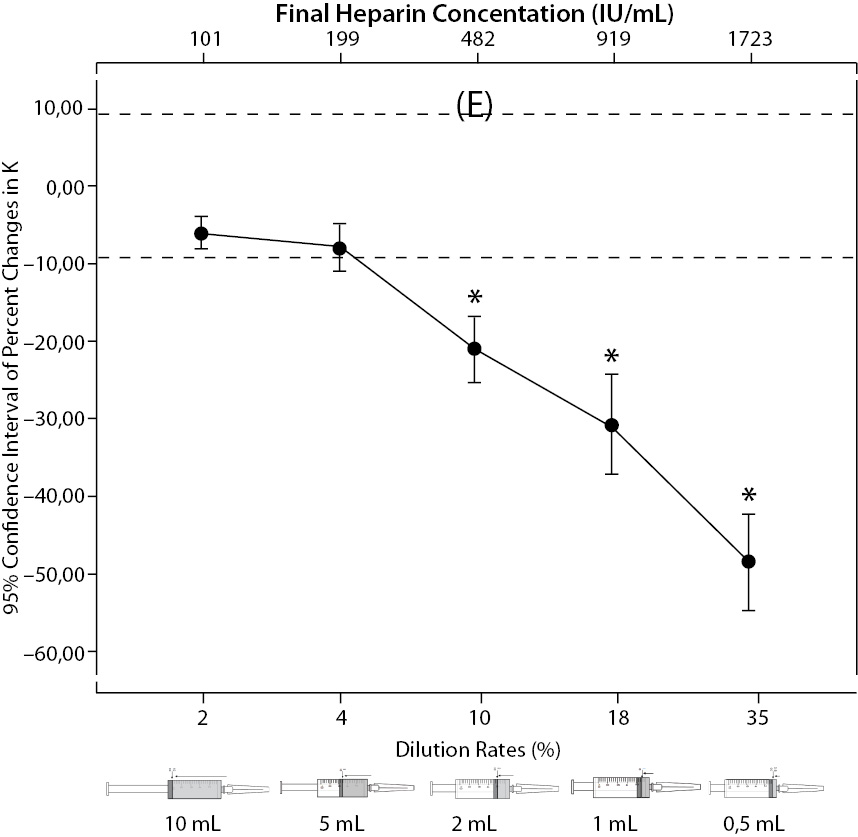

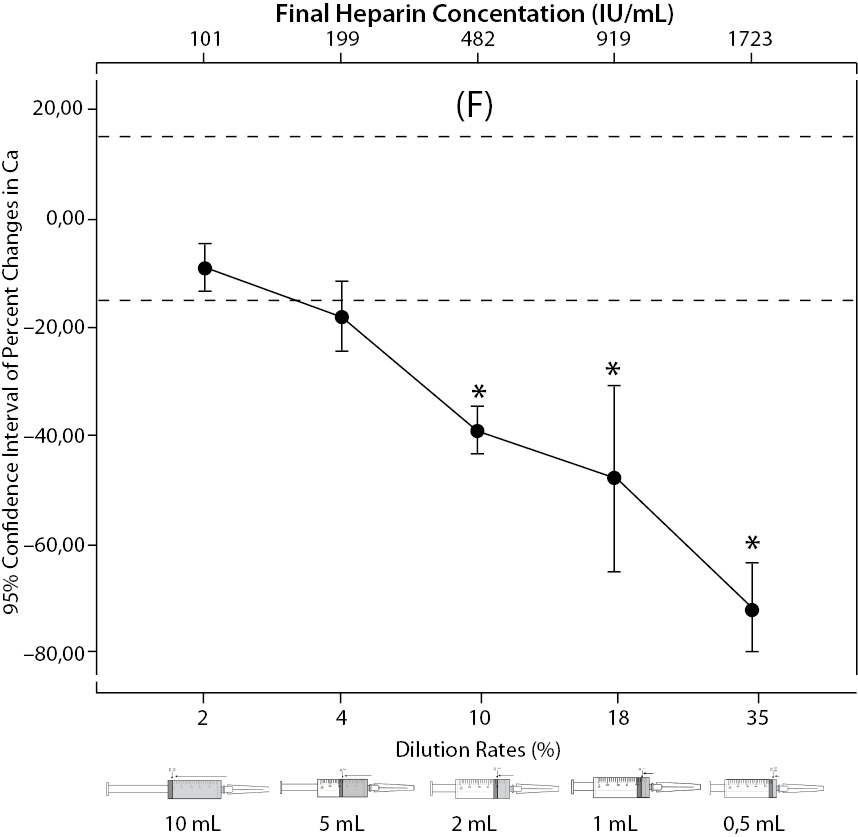

The changes and percent changes for each blood gas parameter with respect to PDRs and FHCs in comparison to acceptable limits for TEa are shown in Figure 2. The all changes in pH and percent changes in pO2 were acceptable; but the percent changes in PDRs and FHCs of 1 mL, 0.5 mL sample volume of pCO2; PDRs and FHCs of 2 mL, 1 mL, 0.5 mL sample volume of Na+; PDRs and FHCs of 2 mL, 1 mL, 0.5 mL sample volume of K+; PDRs and FHCs of 5 mL, 2 mL, 1 mL, 0.5 mL sample volume of iCa2+ were unacceptable according to TEa limits of RiliBAK (10).

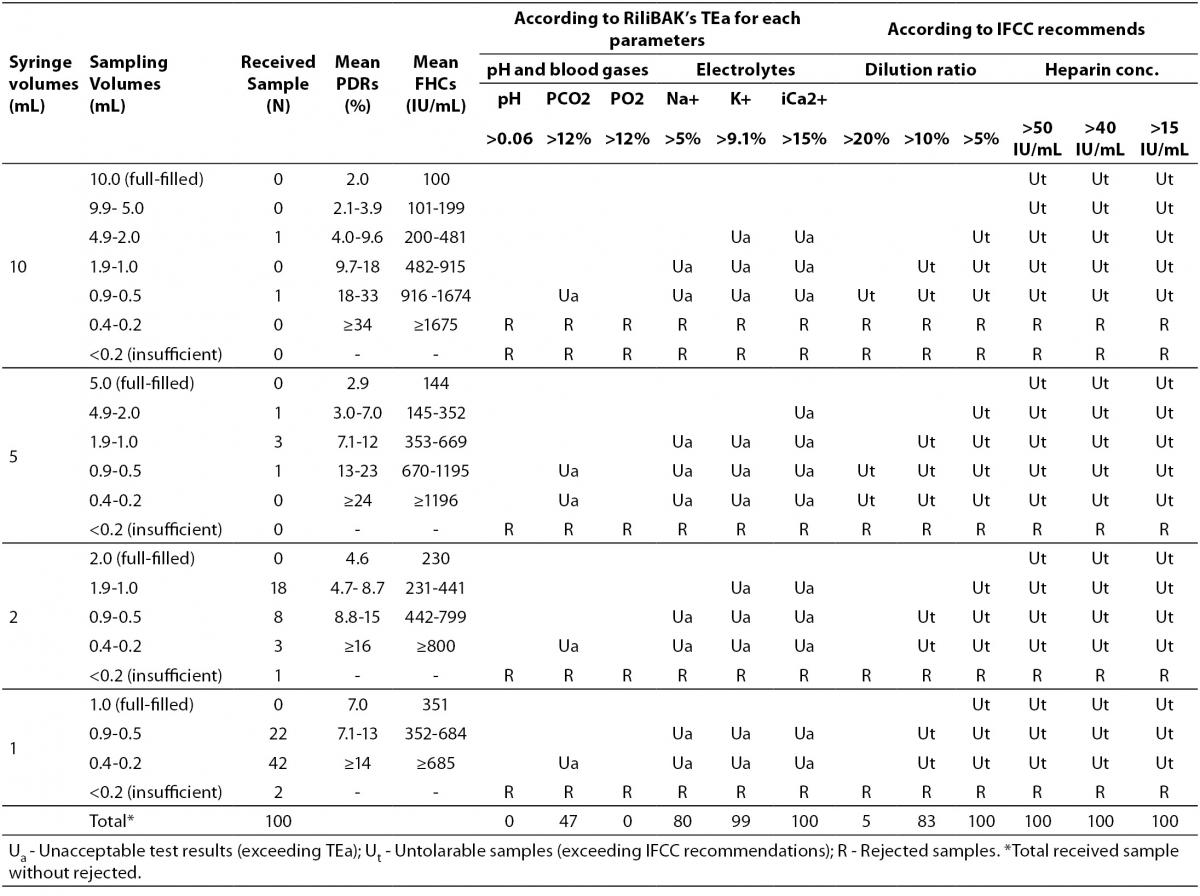

Table 4. The erroneous results due to nonstandardized sampling according to RiliBAK’s TEa.

Figure 2. The changes in pH (A) and the percent changes in pCO2 (B).

Figure 2. The changes in pO2 (C), Na+ (D), K+ (E), iCa+2 (F), iMg+2 (G) at different percent dilution ratios and final heparin concentrations according to experiments with 10 mL syringes. They were compared binary with PDRs and FHCs of full-filled syringes The horizontale dotted line indicates the acceptable limits for TEa according to RiliBAK except iMg. *P < 0.05 in post hoccomparisons with full sampling in syringes.

The erroneous results due to the nonstandardized sampling size in random clinical samples according to RiliBAK’s TEa

In our laboratory,the 39% of blood gas samples were received from emergency department, 25% from pediatrics, 17% from chest disease departments, 16% from internal medicine and 3% from surgical departments. The 73% samples were arterial blood and, 27% were venous blood which is preferred for evaluating only acid base status in clinics. It was observed that small volume syringes for blood gas sampling were used more frequently in our hospital (64% with 1 mL-syringes, 29% with 2 mL-syringes, 5% with 5 mL-syringes and 2% with 10 mL-syringes), and the syringes were not full-filled up to their capacity. Three insufficient samples were rejected. It is indicated in Table 4 that nonstandardized sampling caused error above TEa limits of RiliBAK in 47% of pCO2 results, 80% of Na+ results, 99% of K+ results and 100% of iCa2+ results (10).

Discussion

Most errors affecting laboratory test results occur in the preanalytical phase, primarily because of the difficulty in achieving standardized procedures for sample collection. The blood gas collection with liquid heparin in point of care or laboratory testing is one of the sources of preanalytical errors (13-15).

Using liquid heparin as anticoagulant in blood gas collection is caused combined effect by dilution sourced from liquid form (dilutional effect), direct binding of cations by heparin (chemical effect) and contamination with type of heparin salt (we named as compositional effect) were notified by guidelines (7,8). In this study, we used two markers for determining two major effects of liquid heparin: percent dilution ratio is abbreviated PDR for dilutional effect and final heparin concentration is abbreviated FHC for chemical effect. These markers are depended directly on the amount of heparin solution retained in dead space of syringes and needles.

Dead space of syringes is defined as the volume of liquid retained in the hub and needle when the syringe is completely emptied (16). Hansen et al., Hamilton et al. and Bloom et al. measured dead spaces of syringes as 0.09 mL in 1 mL-, 0.20 mL in 5 mL-, 0.25 mL in 10 mL-syringes (3); 0.21 mL in 5 mL-syringes (4); 0.19 mL in 5 mL-, 0.24 mL in 10 mL-syringes (17), respectively. However, in our research we have obtained smaller dead spaces. This difference may be related to the kind of the material the syringes are made of, glass or plastic; as well as the production technique, raw materials, quality of production which all may affect the dead spaces in the syringes. But, the accuracy of measurement system, temperature and other environmental conditions are more important. So, we used a precision balance for measurements (we expressed weights and volumes with three decimals) and Z factor which is a correction factor in the volumetric calculations to compensate for the density of the water at the test conditions.

The dead spaces of syringes were found to increase while the PDRs were found to decrease from small volume syringes to large volume syringes. Usage of small volume syringes can give rise to increased PDRs. Also, FHCs increase if small volume syringes are used. Consequently, the FHCs increase as PDRs increase in syringes.

The dead spaces of needles consist of an important part of total dead space of syringes, especially in 1 mL- and 2 mL- syringes. Nonstandardized application, for example changing syringe needles, also contributes to increased PDRs. The PDRs and FHCs increase, ranging from 4.9% and 245 IU/mL in smallest size (26 G) to 7.6% and 380 IU/mL in largest size (20 G) needles combined with 1 mL-syringe. In daily practice, this nonstandardized application is not a problem because usually the needles in the syringe packages are used or smallest size needles are preferred to cause less pain and technically easier to use.

Hamilton et al. and Ordog et al. recommended standardized blood collection into syringes washed with liquid heparin, since the FHC in syringes washed with liquid heparin is considered to be sufficient (4,5); IFCC recommends that FHC should be equal to 4-6 IU/mL liquid heparin in plastic syringes (6). We determined that even with standardized washing procedure FHCs in full-filled syringes were 100-351 IU/mL for all different volumes; this amount is more than enough for anticoagulation. But, we determined that changes of blood gas results in pH, pCO2, pO2, Na+, K+, iCa2+ were acceptable according to TEa limits of RiliBAK, if samples collect full-filled in syringes (10).

Correct heparin concentrations in blood gas samples are important for anticoagulation. Due to insufficient coagulation blood clots occur and cause incorrect test results or analyzer failure via obstruction of tubings. In clinics, in order to avoid insufficient coagulation they add more heparin to the syringes. We determined that PDRs increased 3-53% and FHCs increased 151-2669 IU/mL when adding heparin to dead spaces of full-filled syringes (data were not shown). It is evident that added liquid heparin will increase the dilutional and chemical error.

Hamilton et al. reported that inexperienced resident staff sampled large volume heparin and small volume blood, then technicians accepted to analyze small volume samples if the volume was greater than the minimum amount required for the analyzer (4). Hutchison et al. reported heparin solution is added to a syringe before sampling because of economical reasons (18); the syringe washed with liquid heparin for blood gas analysis is also still preferred in our hospital because of blood gas syringes cost 2-5 times from routine syringes without additives. Also, nonstandardized sampling size that is less than the standard volume from total capacity of syringe is used for patient’s comfort and for easier application, which is frequently preferred.

But, we determined that nonstandardized sampling size into the syringes changed PDRs and FHCs. In the course of this study, we observed that small volume syringes were used mostly in our hospital and the syringes were not full-filled up to their capacity. The PDRs were found to increase from full volume sampling to smaller volume sampling of syringes. This condition caused a change in diluent-sample (liquid heparin-whole blood) ratio. Nonstandardized sampling size that is less than the total capacity of syringes contributes to PDRs of 2.0-34%. FHCs in nonstandardized sampling size with liquid heparin were higher than IFCC recommendations. FHCs were found increase 1.9 times in 1 mL-, 3.5 times in 2 mL-, 8.3 times in 5 mL-, 17.1 times in 10 mL- syringes in 0.5 mL sampling compared to full volume sampling. As less sample volumes are drawn into the syringes, the PDR and FHCs increase. Also, usually, heparin solutions bought commercially have high concentrations. In our hospital, 5000 IU/mL heparin used for anticoagulation treatment is also frequently used in blood gas sampling. This condition may increase the chemical effects of heparin compared to 1000 IU/mL heparin solutions.

The pCO2 results are lower than acceptable limits for TEa as the sample volume is lower and heparin concentration is bigger; the reason for this is dilutional effect of heparin solution. Also, pO2 results are getting higher (although within allowable range according to RiliBAK) as the concentration of liquid heparin is higher because of two possible reasons: heparin solution itself has pO2 of approximately 20 kPa and in this study we kept samples cooled until analysis which can cause falsely higher values of pO2. Problem with Na+ values is connected with usage of liquid Na+ salt of heparin as anticoagulant (compositional effect) - as the percent of heparin is higher, Na+ value is more falsely elevated. Because of ability of heparin molecule to bind electrolytes (chemical effect), values of iCa2+, K+ and iMg2+ are more (falsely) lower as the concentration (percentage) of liquid heparin is higher.

In our hospital, blood gas sampling is done most frequently with small volume syringes while sampling size is nonstandardized and less than the full volume capacity of the syringe. A dramatic result of this nonstandardized technique is that 47% of pCO2 results, 80% of Na+ results and nearly 100% of K+ and iCa2+ results are found to contain error above the TEa according to RiliBAK (10).

The calculated percent changes of pCO2 and electrolyte results due to nonstandardized sampling in patient samples were found to exceed the acceptable error rates in PDR considered untolerable by IFCC. IFCC declares that the effects up to 10% dilution on blood gases results and up to 5% on electrolytes results are tolerable for most practical purposes (6). Also, IFCC declares that ionized calcium and magnesium measurements are affected by FHCs of samples which should not be higher than 15 IU/mL in tubes, 40 IU/mL in syringes and 50 IU/mL in capillary tubes (19,20). Considering IFCC recommendations about the PDRs and FHCs, it was observed that 83% of blood gas results and 100% of blood electrolytes results were affected from high PDR and 100% of blood electrolytes results were affected from high heparin concentrations.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the nonconformities in sampling for blood gas analysis are causing unacceptable test results for pCO2 and electrolytes. The danger from nonstandardized blood collection into the syringe washed with liquid heparin should be careful assessed. For preventing serious medical errors due to nonstandardized blood gas sampling, electrolyte balanced dry heparin may be recommended. If not possible, standardized techniques which the dead space of the syringes only fills with heparin and samples collect to total capacity of syringe should be used. Also, medical errors due to incorrect test results should always be followed by clinical laboratory management for laboratory testing and point of care comittee for point of care testing. Standardized procedures should be prepared and applied along with education of staff about blood gas samples.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Erol Medikal (Istanbul, Turkey) which is the sales office of Nova Instruments in Turkey for blood gas reagents and technical supports in blood gas analysis.