Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) has become a global health concern over the past few decades, worldwide (1-3). General risk factors for developing MetS are abdominal obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia. In addition to these, the characteristics of MetS include proinflammatory and prothrombotic state, hyperuricemia and gout, microalbuminuria, and electrolyte disbalance (2,4-6).

Many genetic polymorphisms might be involved in the pathogenesis of MetS (7). The genes responsible for the metabolism and transport of lipids, regulation of arterial blood pressure, the transport, regulation and metabolism of glucose, hormonal regulation and other factors might contribute to the development of MetS (7-9).

The fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are members of the superfamily of small (14-15 kDa) intracellular lipid-binding proteins (LBPs) (10). LBPs play various important roles in signaling, regulation, membrane trafficking, immune response, lipid metabolism and transport (11). Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (I-FABP or FABP2) is one of nine different FABPs identified in mammals, besides liver, heart and muscle, adipocyte, epidermal, ileal, brain, myelin and testis FABP (10,12). The primary function of all FABPs is the regulation of fatty acid uptake (FA) and intracellular transport.

The genes that encode FABPs are dispersed throughout the genome and their structure is well conserved (13). Each gene consists of four exons separated by three introns of variable sizes (13). The FABP2 gene encodes for intestinal fatty acid-binding protein, which is involved in the uptake, intracellular metabolism, and/or transport of long chain fatty acids (13). The gene consists of 3382 nucleotides located in the chromosomal region 4q28-4q31, arranged in four exons containing ~700 bp and three introns containing ~2650 bp (14,15). I-FABP (FABP2) protein consists of 131 amino acid residues and has a high content of β-strand structure. The internal binding cavity is capable of binding one molecule of ligand, with affinity depending on fatty acid identity (14). I-FABP (FABP2) has two forms (alanine-containing (A54) or threonine-containing (T54) protein which display differences in binding and transporting fatty acids across cells (16). Polymorphism is due to the transition from G to A at codon 54 of the FABP2 gene and results in a substitution of alanine by threonine (Ala54Thr) in exon 2 (rs1799883). Threonine-containing protein has greater ability to transport long chain fatty acids than alanine-containing protein (16). The Ala54Thr polymorphism of the fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene can be commonly found in around 30% of the most populations and is associated with insulin resistance (17), dyslipidemia and obesity (18,19), which are all cardinal components of MetS. Three different meta-analyses evaluated the effects of the Ala54Thr polymorphism on body mass index (BMI) (20), insulin resistance (21) and fasting lipids (18) in different world populations. The first analysis showed that there is no association between Ala54Thr polymorphism and BMI (20). However, weak association appears to be present between this polymorphism and insulin resistance (21). Finally, strong association was found between the Thr54 allele and higher levels of triglycerides (TGs) and LDL-cholesterol, and lower levels of HDL-cholesterol (18).

As FABP2 is involved in the transport of fatty acids inside intestinal cells and therefore might affect the fatty acids composition of chylomicron triglycerides, we hypothesized that this polymorphism might be involved in the pathogenesis of MetS at least as its dyslipidemic component.

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between FABP2 Ala54Thr genetic polymorphism and metabolic syndrome and some biochemical and anthropological parameters in elderly subjects.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional and comparative study, the final step of a large longitudinal national multicenter epidemiological study of chronic diseases in Croatian population, conducted by the researchers and medical team from the Institute for Medical Research and Occupational Health and their collaborators. Study design was already described in details elsewhere (22,23). In short, the cohort was established in 1969, with 3 follow-ups. The last one dates from 2006/2007 when participants were over 70 years old. Only free-living participants, able to look after themselves and manage their everyday activities were included in the study. The study involved 345 elderly participants among whom the prevalence of MetS was investigated. Of these, 316 participants had enough blood sample volumes for all biochemical analyses, DNA isolation and genetic testing. With regard to the presence or absence of MetS according to the criteria of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (24), subjects were divided into two subgroups, MetS(+) and MetS(-). MetS(+) criteria was satisfied if waist circumference was ≥ 94 cm for men or ≥ 80 cm for women plus any of two following criteria: fasting glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L (or previously diagnosed adult diabetes mellitus and antidiabetic therapy), triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L, HDL-cholesterol < 1.03 mmol/L for men or < 1.29 mmol/L for women, and blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg.

All participants signed the informed consent form and the study was approved by the Institute’s Ethics Committee.

Subjects

The study included 140 men and 176 women whose median age was 78 (range 71-93 years) and 77 (range 71-92 years), respectively. Blood sampling, medical examination and interviews were performed between 07.00 and 12.00 a.m. Height, weight and waist circumference were measured according to the International Biological Program Protocol (25). Waist circumference was taken on midway between the 10th rib and the top of the iliac crest (at the level of the umbilicus) using a flexible nonstretchable plastic tape and was approximated to the nearest 0.1 cm. Blood pressure was measured in the sitting position after 10-20 min rest using a mercury sphygmomanometer (Reister, Jungingen, Germany). Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated according to equation: MAP = [(2 x diastolic) + systolic] / 3 (26). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the formula: mass (kg) / body height (m)2. Smoking status was defined in line with the questionnaire data: smokers were defined as all ex-smokers and active smokers, whereas non-smokers were those that had never smoked.

Blood sampling

Blood samples were collected in the K2EDTA tubes and serum separator tubes (BD Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, Plymouth, UK) by puncture from an antecubital vein after an overnight fasting. Serum samples were stored at -20°C until analyses.

Methods

Serum concentration of glucose, total proteins and C-reactive protein (CRP) were determined by standardized methods on Beckman Coulter AU400 selective autoanalyzer (Beckman Coulter, Tokyo, Japan) using reagents from the same manufacturer (Beckman Coulter, Hamburg, Germany). Lipid parameters (total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides) were determined with enzymatic methods on the Roche COBAS MIRA autoanalyzer using reagents from Boehringer-Manheim Diagnostics and Hoffmann-La Roche (Roche diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). LDL-cholesterol was calculated according to the Friedwald formula (27).

DNA was extracted from whole blood by automatized salting out methodwith a Biosprint 15 DNA-Blood Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) on a KingFisher automatic system (Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). FABP2 genetic polymorphism (2445G®A) Ala54Thr was genotyped with PCR-RFPL method (28), using Hha I restriction endonuclease (Fermentas International Inc., Burlington, Canada). Polymerase chain reactions of exon 2 were performed with primers (Sigma-Aldrich Chimie GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany), whose sequence was previously described (28). The reactions were performed in Eppendorf Mastercycler 3350 (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) using 500 ng of genomic DNA, 7.5 x 10-3 of each primer, 15 mM MgCl2 in buffer, 10 nmol of each dNTP and 0.6 U of Fast start TaqDNA-polymerase (Roche, Manheim, Germany) in 25 ml of reaction mixture. Each of 30 cycles consisted of 30 seconds (s) at 94 °C, 45 s at 58 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C, followed by a 5-min extension at 72 °C. 6 ml of PCR-products were digested by 12 U of Hha I restriction endonuclease (Fermentas, Burlington, Canada) at 37 °C for 16 hours. 180-bp fragments were cleaved into 99-and 81-bp fragments (Ala54) or were undigested (Thr54). Fragments were visualized on 3%-agarose gel with ethidium bromide.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows 20.0 (Chicago IL USA). Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s c2-test. Distribution normality for continuous variables was performed by Levene’s test. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and those without normal distribution were expressed as median and 25thand 75th percentiles. Group comparison of continuous variables was performed by Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney test, according to distribution normality. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

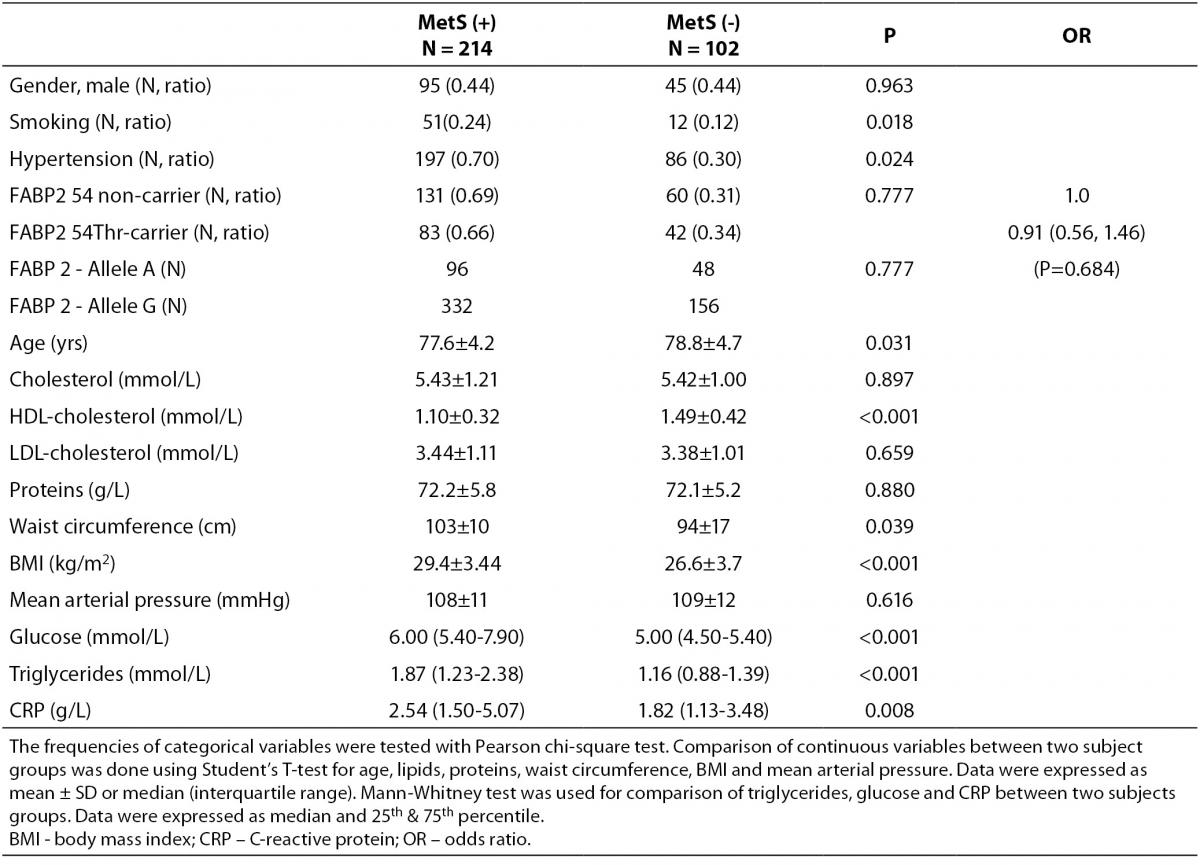

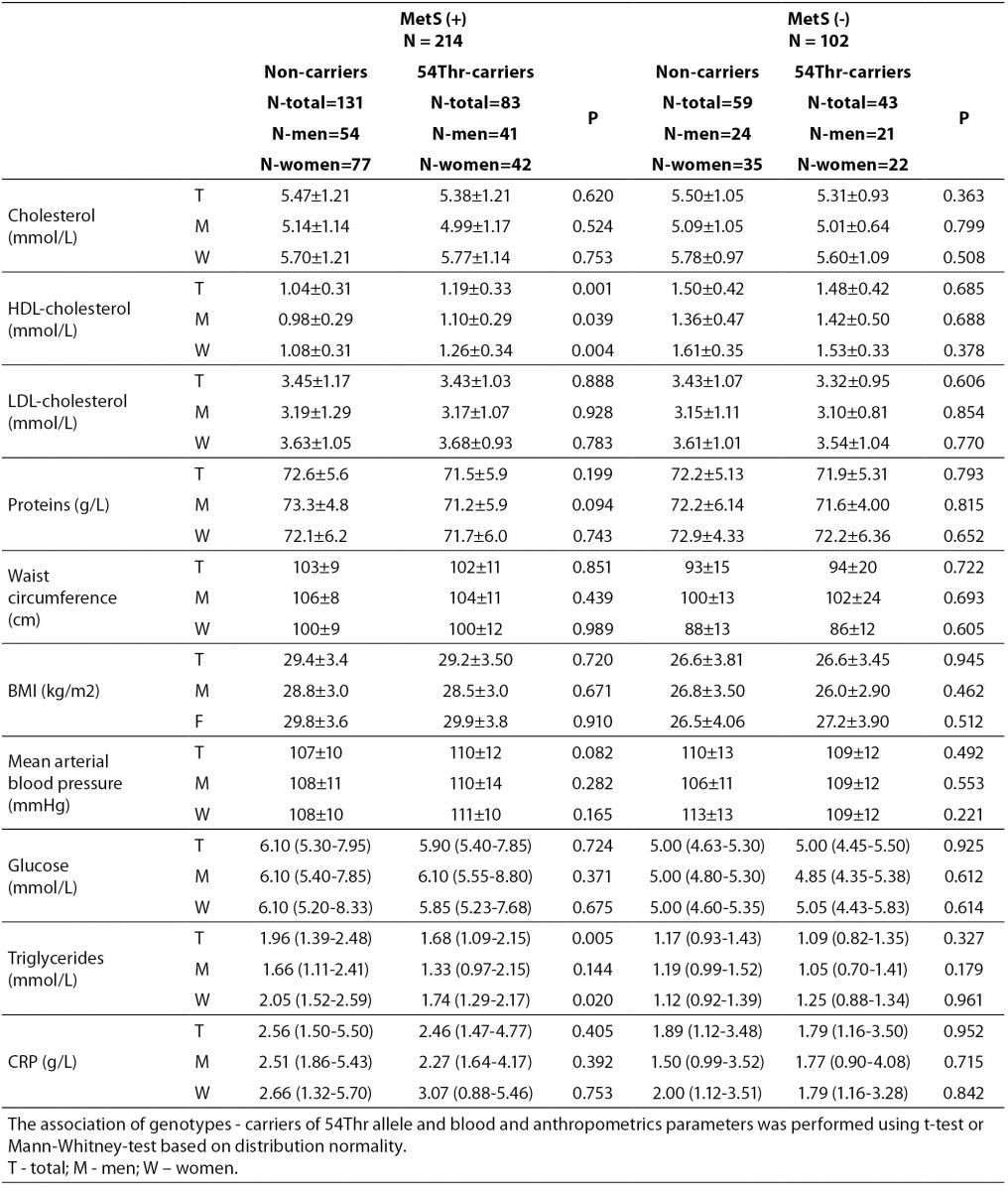

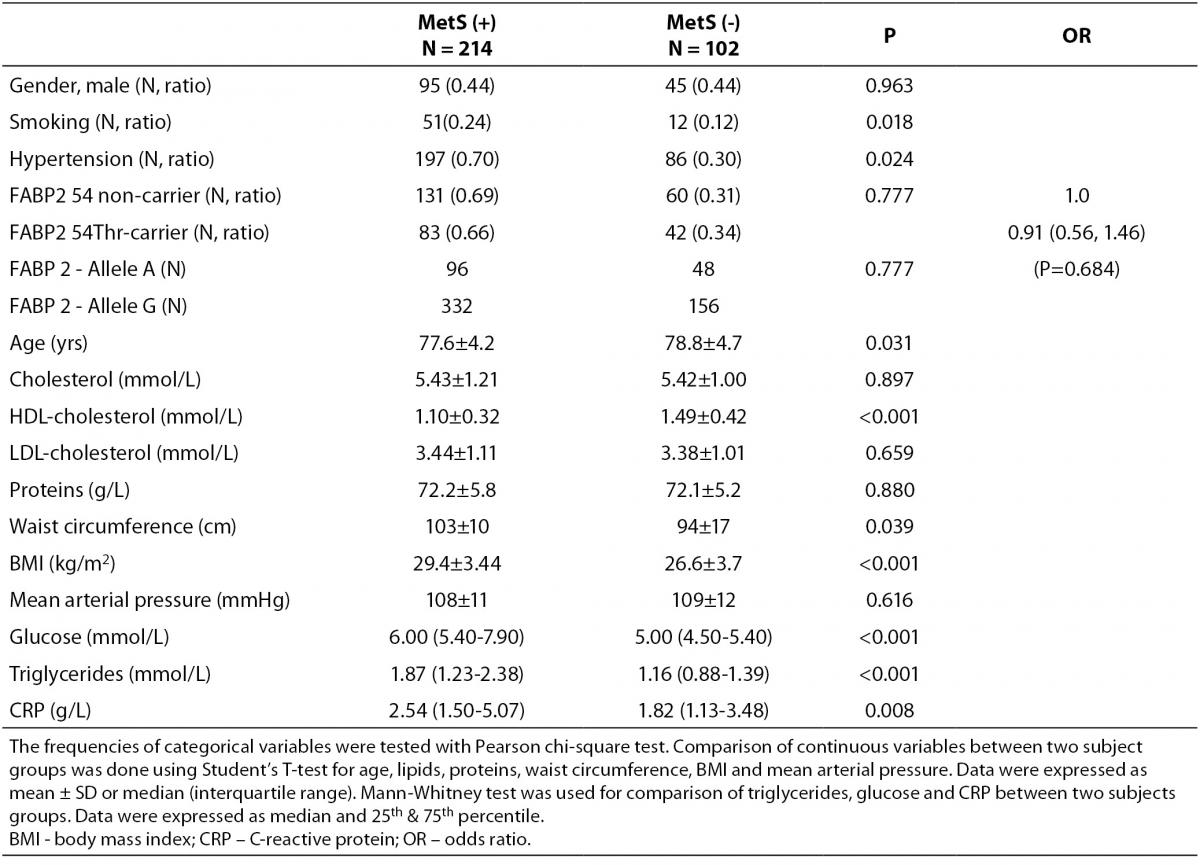

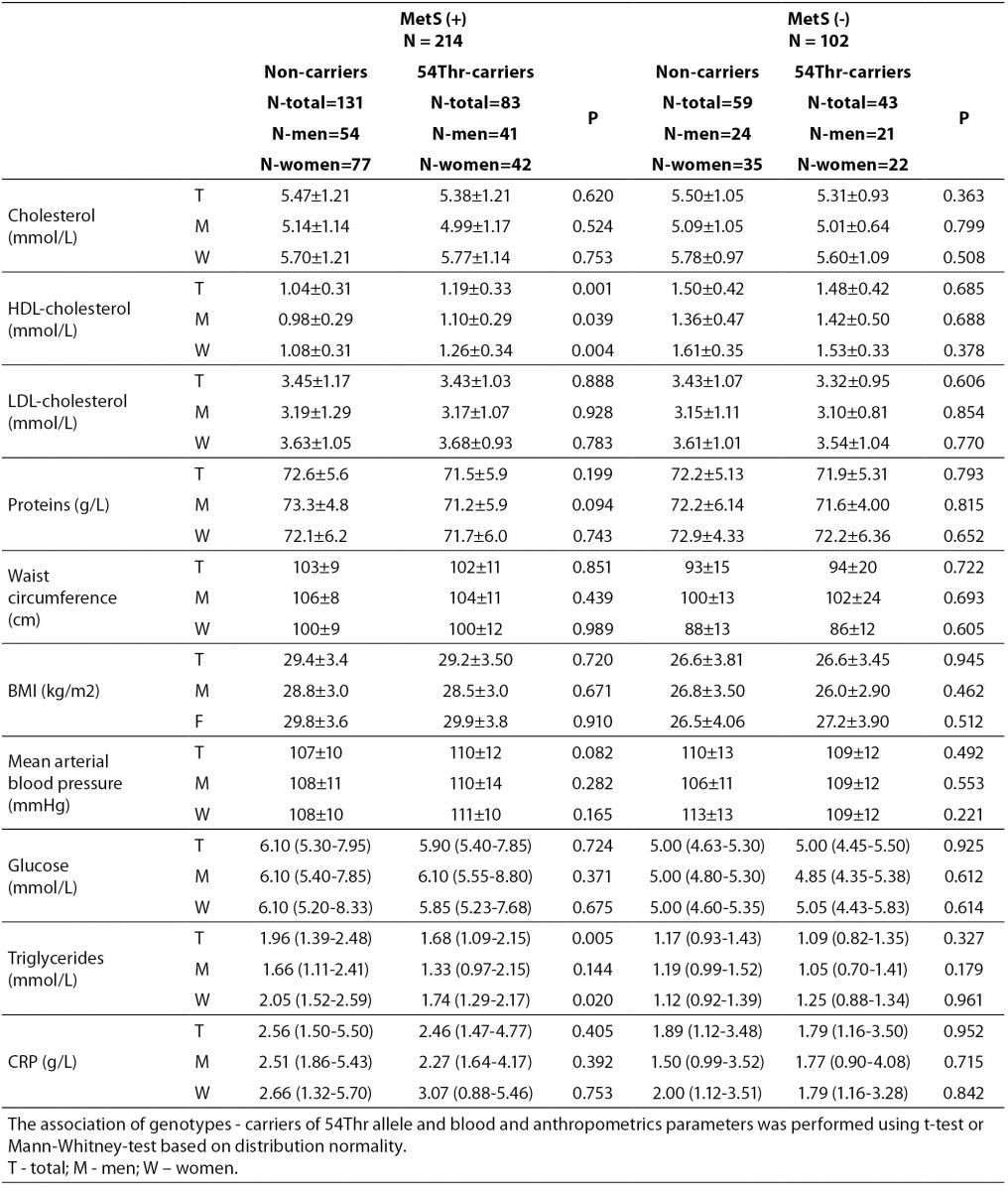

According to the IDF definition of MetS, 68% of a total of 316 subjects involved in the study (Table 1) were affected by MetS. As expected, there were significant differences in the concentrations of glucose and HDL-cholesterol, as well as in waist circumference values and the frequency of hypertension between MetS(-) and MetS(+) groups. Additionally, the frequency of smokers and the concentrations of CRP were significantly higher in MetS(+) subjects. There was no difference in the frequencies of FABP2 Ala54Thr genotypes between the studied groups. The genotype frequencies for Ala/Ala, Ala/Thr and Thr/Thr genotype were 60, 36 and 6 in MetS(-), and 131, 70 and 13 in MetS(+), respectively. Observed genotype frequencies of the FABP2 gene polymorphism were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in both subjects’ groups. Ala/Ala genotype was considered to be the subgroup of Thr54 non-carriers, while heterozygous Ala/Thr and homozygous Thr/Thr genotypes were considered as subgroup of Thr54 carriers. Table 2 presents biochemical and anthropometric data for two genotype subgroups, separately for groups with and without MetS. Significant difference was observed for lipid concentrations between carriers and non carriers in MetS(+) subjects. The results of Mann-Whitney test showed that triglyceride concentration was significantly lower (P = 0.050) in whole group, while genderwise the difference was evident only in female subjects (P = 0.020). T-test showed that mean HDL cholesterol concentrations of Thr54-carriers were significantly higher in whole group (P = 0.001), and for both genders (men P = 0.039; women P = 0.004) as compared to Thr54 non-carriers. There is no any difference between carriers and non-carriers in subjects without MetS for neither of parameters tested.

Table 1. Characteristics of study subjects according to metabolic syndrome presence.

Table 2. Biochemical and anthropometric values in subjects with and without metabolic syndrome according to FABP 2 Ala54Thr polymorphism.

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that there is no significant difference in the frequency of FABP2 Ala54Thr polymorphism between the subjects with and without MetS according to the IDF criteria. As expected, there is a significant difference in lipid parameters between these subjects. Significantly lower TGs and higher HDL-cholesterol mean concentrations in carriers of 54Thr allele as compared to non-carriers indicate that the 54Thr allele might have a protective role in subjects with MetS after an overnight fast. Gender and age as covariates showed a statistically significant but clinically irrelevant effect of the Thr54 carriers on total and LDL-cholesterol concentrations, as well as on waist circumference and BMI levels.

There are many conflicting conclusions in investigations of Ala54Thr polymorphism and lipid profile. The reduction in plasma triglyceride level in the carriers of Thr allele was found in sixteen healthy postmenopausal women in a cross-over designed feeding trial in which these women were undergoing a high-fat diet (29). The lowest values for triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) cholesterol and TRL phospholipids were found in women homozygous for the Thr54-encoding allele, whereas the highest values were found in men homozygous for the Thr54-encoding allele (30). This study was designed as a clinical trial involving subjects who were subject to a low-fat American Heart Association–type diet. A Spanish cross-sectional study did not find any difference in anthropometric and lipid parameters between genotypes in subjects with or without MetS (19). The results of our study also showed the lack of association between the Thr54/Ala54 and Thr54/Thr54 FABP2 genotypes and MS.

The meta-analysis that included investigations published before June 2009 showed the opposite results for lipid parameters in the fasting state (18). This meta-analysis involved adults of at least 18 years of age, from different populations, and with different health disorders. Several studies with obese subjects reported that 54Thr allele was not associated with higher TGs or lower HDL-cholesterol fasting concentrations. However, the general conclusion was that 54Thr allele was associated with higher concentrations of TGs and lower concentrations of HDL-cholesterol, which is contradictory to our results.

FABP2 Ala54Thr polymorphism may affect lipid levels depending on the composition of dietary intake. Chamberlain et al. (17) concluded that limiting dietary saturated fat intake may be particularly important among the carriers of the A allele of FABP2 among young adults. They did not find any difference in lipid profiles in the fasting state. A large Japanese case-control study showed that Thr54 represented a risk factor for myocardial infarction in subjects with MetS, although it was related to reduced fasting glucose and total cholesterol concentrations (31).

In vitro studies showed that FABP2 is responsible for postprandial transport and partitioning of long-chain free fatty acids (FFA) toward TG synthesis (32). Overexpression of FABP2 in HIEC-6 cells also showed aminor effect on monounsaturated fatty acid oxidation. THr54 isoform of FABP2 has higher binding affinity of substrate oleate and arachidonate than Ala 54 isoform (33).

It can be expected that polymorphisms of FABP2 will not affect fasting lipid values because they are responsible for postprandial fatty acid transport. General conclusion might be that literature data are inconsistent and depend on study designs, number of subjects, age, ethnicity, clinical trials etc.

There are several limitations to this investigation. The study included subjects over 70 years of age and the frequency of MetS is higher in older than in younger subjects. Furthermore, previous follow-ups lack data and this might explain dyslipidemia induced by Ala54Thr polymorphism. Determination of free fatty acids (FFA) and composition of FFA also might be useful in explaining the above mentioned polymorphism association with MetS because of different substrate affinity of genetic variants (14). The lack of data on lipid concentrations in postprandial state and on subjects who received statin therapy represents an additional weakness of this study. However, an added value of this study is the fact that this is the first such study on the effects of FABP2 Ala54Thr polymorphism in Croatian subjects. Results of this study might contribute to the understanding of pathophisiology of dyslipidemia and MetS, as well as of other related multifactorial disorders.

In conclusion, there is evidence that FABP2 genetic variations alter triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol concentrations in elderly subjects with MetS. These genetic variations might be useful markers for understanding dyslipidemia in MetS.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the University of Applied Health Studies-Zagreb, Croatia and the Scientific Project Grant 022-0222411-2407 of the Croatian Ministry o of Science, Education and Sport. We want to thank to Jasna Jurasovic, PhD for her engagement in collecting blood samples and helpful suggestions for writing the manuscript.

Notes

Potential conflict of interest

Not declared.

References

1. Tanner RM, Brown TM, Muntner P. Epidemiology of Obesity, the Metabolic Syndrome, and Chronic Kidney Disease. Curr Hypertens Rep 2012;14:152-9.

2. Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008;28:629-36.

3. Thiruvagounder M, Khan S, Sultan Sheriff D. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in a local population in India. Biochem Med 2010;20:249-52.

4. Pašalić D, Marinković N, Feher-Turković L. Uric acid as one of the important factors in multifactorial disorders – facts and controversies. Biochem Med 2012;22:63–75.

5. Blaton VH, Korita I, Bulo A. How is metabolic syndrome related to dyslipidemia? Biochem Med 2008;18:14-24.

6. Farhangi MA, Ostadrahimi A, Mahboob S. Serum calcium, magnesium, phosphorous and lipid profile in healthy Iranian premenopausal women. Biochem Med 2011;21:312-20.

7. Povel CM, Boer JM, Reiling E, Feskens EJ. Genetic variants and the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2011;12:952-67.

8. Garaulet M, Madrid JA. Chronobiology, genetics and metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Lipidol 2009;20:127-34.

9. Dujic T, Bego T, Mlinar B, Semiz S, Malenica M, Prnjavorac B, et al. Association between 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 gene polymorphisms and metabolic syndrome. Biochem Med 2012;22:76-85.

10. Sacchettini JC, Gordon JI, Banaszak LJ. The Structure of Crystalline Escherichia coli-derived Rat Intestinal Fatty Acid-binding protein at 2.5-Å Resolution. J Biol Chem 1988;263:5815-9.

11. Lin HH, Han LY, Zhang HL, Zheng CJ, Xie B, Chen YZ. Prediction of the functional class of lipid binding proteins from sequence-derived properties irrespective of sequence similarity. J Lipid Res 2006;47:824-31.

12. Hanhoff T, Lücke C, Spener F. Insights into binding of fatty acids by fatty acid binding proteins. Mol Cell Biochem 2002;239:45-54.

13. Chmurzynska A. The multigene family of fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs): Function, structure and polymorphism. J Appl Genet 2006;47:39-48.

14. Weiss EP, Brown MD, Shuldiner AR, Hagberg JM. Fatty acid binding protein-2 gene variants and insulin resistance: gene and gene-environment interaction effects Physiol Genomics 2002;10:145-57.

15. Sweetser DA, Birkenmeier EH, Klisak IJ, Zollman S, Sparkes RS, Mohandas T, et al. The Human and Rodent Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein Genes. J Biol Chem 1987;262:16060-71.

16. Zhang F, Lücke C, Baier LJ, Sacchettini JC, Hamilton JA. Solution structure of human intestinal fatty acid binding protein with a naturally-occurring single amino acid substitution (A54T) that is associated with altered lipid metabolism. Biochemistry 2003;42:7339-47.

17. Chamberlain AM, Schreiner PJ, Fornage M, Loria CM, Siscovick D, Boerwinkle E. Ala54Thr polymorphism of the fatty acid binding protein 2 gene and saturated fat intake in relation to lipid levels and insulin resistance: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Metabolism 2009;58:1222-8.

18. Zhao T, Nzekebaloudou M, lv J. Ala54Thr polymorphism of fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene and fasting blood lipids: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2010;210:461-7.

19. de Luis DA, Gonzalez Sagrado M, Aller R, Izaola O, Conde R. Metabolic syndrome and ALA54THR polymorphism of fatty acid-binding protein 2 in obese patients. Metabolism 2011;60:664-8.

20. Zhao T, Zhao J, Lv J, Nzekebaloudou M. Meta-analysis on the effect of the Ala54Thr polymorphism of the fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene on body mass index. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011;21:823-9.

21. Zhao T, Zhao J, Yang W. Association of the fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene Ala54Thr polymorphism with insulin resistance and blood glucose: a meta-analysis in 13451 subjects. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2010;26:357-64.

22. Pašalić D, Dodig S, Corović N, Pizent A, Jurasović J, Pavlović M. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an elderly Croatian population - a multicentre study. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:1650-7.

23. Pizent A, Pavlovic M, Jurasovic J, Dodig S, Pasalic D, Mujagic R. Antioxidants, trace elements and metabolic syndrome in elderly subjects. J Nutr Health Aging 2010;14:866-71.

24. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009;120:1640-5.

25. Weiner JS, Lourie JA. Practical Human Biology. Academic Press., London, England (1981).

27. Friedewald WT. Levy RI, Fredricson DS. Estimation of the concentrations of low density lipoprotein-cholesterol in plasma, without use the preparative centrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499-502.

28. Baier LJ, Sacchettini JC, Knowler WC, Eads J, Paolisso G, Tataranni PA, et al. An amino acid substitution in the human intestinal fatty acid binding protein is associated with increased fatty acid binding, increased fat oxidation, and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 1995;95:1281-7.

29. cColley SP, Georgopoulos A, Young LR, Kurzer MS, Redmon JB, Raatz SK. A high-fat diet and the threonine-encoding allele (Thr54) polymorphism of fatty acid-binding protein 2 reduce plasma triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Nutr Res 2011;31:503-8.

30. Gastaldi M, Dizière S, Defoort C, Portugal H, Lairon D, Darmon M, Planells R. Sex-specific association of fatty acid binding protein 2 and microsomal triacylglycerol transfer protein variants with response to dietary lipid changes in the 3-mo Medi-RIVAGE primary intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1633-41.

31. Oguri M, Kato K, Yokoi K, Itoh T, Yoshida T, Watanabe S, et al. Association of genetic variants with myocardial infarction in Japanese individuals with metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis 2009;206:486-93.

32. Storch J, Thumser AE. Tissue-specific functions in the fatty acid-binding protein family. J Biol Chem 2010;285:32679-83.

33. Pratley RE, Baier L, Pan DA, Salbe AD, Storlien L, Ravussin E, Bogardus C. nEffects of an Ala54Thr polymorphism in the intestinal fatty acid-binding protein on responses to dietary fat in humans. J Lipid Res 2000;41:2002-8.