Introduction

The pneumatic tube system (PTS) has become a commonly used method of transport in hospitals; it is inexpensive and efficient. PTS reduces delivery delays of patient samples to the central laboratory.The laboratory turnaround time (TAT) represents a quality indicator of the efficiency of the laboratory process. The TAT is dependent on a number of extra- and intra-laboratory factors, all of which should be considered in TAT improvement plans. TAT is defined as the period of time for blood draw, sample delivery, analysis, and results. Physicians and other clinical staff usually assess the quality of laboratory service by the period of elapsed time between analysis and test results, and they often assume faster is better. The TAT can be decreased by the use of modern and rapid automated systems. After analysis, the results can be observed within seconds through electronic data links. The delivery of the samples to the laboratory for analysis is the most time-consuming step of the process. The use of a rapid sample delivery system, such as PTS, will accelerate the laboratory TAT further. In addition, PTS represents a practical and efficient approach to sample distribution (1,2).

Although PTS significantly reduces the laboratory TAT, the samples do withstand forces of pressure during transport, such as changes in air pressure, movement or shaking of blood in the test tube, vibrations, and sudden accelerations and decelerations These pressures can potentially affect laboratory measurements during tests, such as blood gas analysis, routine haematology and coagulation tests, and spectrophotometric analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid. These forces also can induce cellular disruption (3). In the literature, various studies have been conducted on the effects of PTS on hemolysis. A study by Stair and colleagues reported no significant differences in the frequency of hemolysis between specimens delivered by hand or by PTS (4). The PTS significantly reduces laboratory TAT, and for this reason, the PTS has been used frequently for the transport of medical samples to the laboratory. During transport, the quality of thesample can be affected by exposure to extreme temperature and physical forces. During PTS transport, sample quality can be affected by the exposure to rapid acceleration, radial gravity forces, sudden decelerations, and other extreme temperature and physical forces. These violent forces may contribute to pre-analytical errors due to erythrocyte and lymphocyte rupture (5). A study by Weaver and colleagues compared the effects of PTS and manual transport on the results of 15 chemical tests and 6 hematologic procedures. The only difference they observed in PTS specimens was that the activity of lactate dehydrogenase exceeded the precision of the test. However, the remaining tests - serum sodium, potassium, chloride, carbon dioxide, total protein, albumin, calcium, glucose, creatinine, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate transaminase, acid phosphatase, uric acid, leukocyte count, erythrocyte count, haemoglobin, haematocrit, prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) - were not affected by PTS (6). Sodi et al. emphasized that each laboratory should investigate the effects of the specific PTS used by the laboratory on the samples (7). Published studies indicate various differences in PTS used by different laboratories. Therefore, the PTS should be evaluated for its effects on sample quality.

In our study, we investigated the PTS in our hospital for its potential influence on blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation, and coagulation tests (PT and aPTT).

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted this week-long, prospective cross-sectional study in May 2012 in the clinical biochemistry laboratory of the Evliya Celebi Training and Research Hospital in Dumlupinar University, Kütahya City, Turkey. The study involved 45 healthy blood donors (24 males and 21 females; mean age, 39 years; range, 35–45 years). We submitted this study to the Internal Review Board and received approval from the local Human Research Ethics Committee. All volunteers provided informed consent.

Collection of blood samples

Blood samples were collected from donors between 9 and 10 a.m. during a one-week period, after a 12-hour fast. All samples were drawn by the same expert phlebotomist according to the recommendations of the Clinical Laboratory Institute (CLSI) (8). For each donor, blood samples were collected into 3 pairs of tubes, giving a total of 6 tubes. For blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation analysis, the blood was collected into 2.0 mL dipotassium (K2)ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid(EDTA) vacuum tubes (BD Vacuteiner® BD-Plymouth, UK) (Ref.No.368841). For coagulation analysis, the blood was collected into 2.0-mL 9NC coagulation sodium citrate 3.2% vacuum tubes (Vacuette®, Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmunster, Austria [Ref.No.454322]).

Pneumatic tube system

The PTS used in our hospital (Pneumatic Tube Systems MP10000, Version 2.3.0; Sumetzberger GmbH, Vienna, Austria) has 3 subsystems, 31 stations and a constant speed of 6 m/s. Our PTS carriers are 160 mm in diameter and 440 mm in length. Two kinds of carrier inserts (sponge-rubber and plastic-bag) are used to protect the samples during PTS transportation. In this study, we used the PTS station on the hospital’s top floor (floor), which is furthest from the laboratory.

Methods

Collected blood samples were divided into 2 groups without delay. Group 2 samples were immediately transported to the clinical laboratory by the laboratory staff. Group 1 samples were immediately transported to laboratory by the PTS. Upon reaching the laboratory, all blood samples were tested for coagulation analysis by centrifugation at 3500 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature followed by analysis of plasma samples for PT and aPTT (Thrombolyzer XRC; Behnk Elektronik GmbH & Co. KG, Norderstedt, Germany; Hyphen BioMed Reagent, Neuville-Sur-Oise, France [Ref.No.CK551M,CK515K]). The remaining blood samples were analyzed promptly for blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation. Blood cell counts were performed using Coulter Gen-Sautomated haematology instruments (Beckman Coulter LH 780 Gen-S System; Miami, FL, USA; original reagents [Ref.No.8448155]). Erythrocyte sedimentation analysis was performed using an Alifax sedimentation analyser (Alifax-SPA Test 1 HTL;Polverara, Italy).

Statistical analysis

The differences between samples in the 2 groups were assessed for significance by paired Student’s t-test after normality was checked by the D’Agostino-Pearson’s omnibus test; P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Non-normal distributions were not observed. Normally distributed results were grouped as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

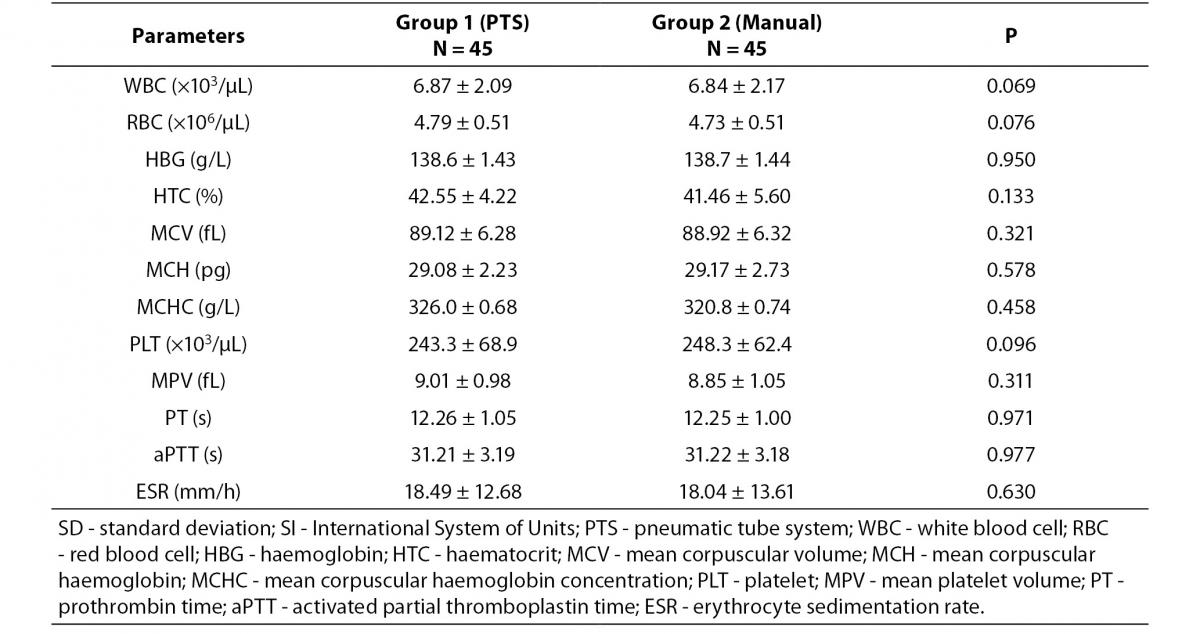

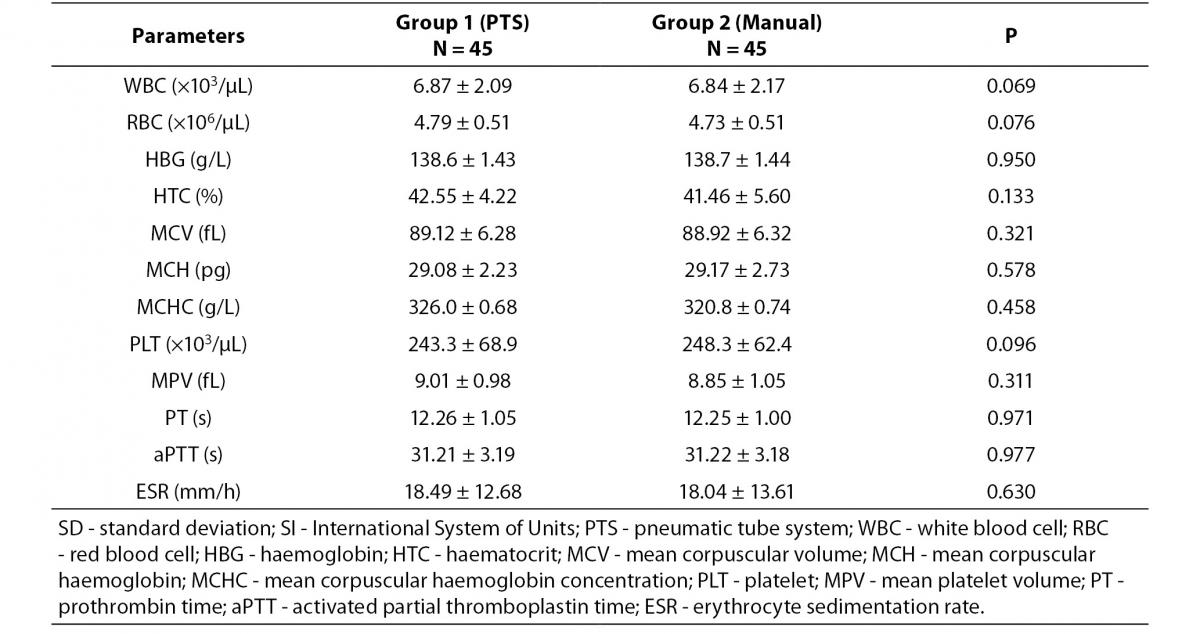

The comparison of results between blood samples delivered to laboratory by PTS and by laboratory staff is shown in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed (P values from 0.069 to 0.977).

Table 1. Blood analysis results (± SD) and statistical differences between blood samples delivered to laboratory by PTS and by laboratory staff.

Discussion

The PTS is becoming a common method for transporting samples in hospitals and is considered effective because of its speed and efficient use by employed staff. However, this type of transport method has been cited as potentially affecting certain laboratory measurements (9,10).

Published studies show that researchers have investigated the influence of PTS on different test parameters and have identified differences among different types of PTS. Collinson et al. reported significant changes in pO2 in samples that had been transported by PTS; however, pH and pCO2 were not affected by PTS. In a subsequent study, they transported the samples with PTS but used a pressure-proof container; the previously observed differences were absent (11). Keshgegian et al. reported that PTS transport of samples did not have significant effects on pO2, pCO2, pH, complete blood counts or standard chemical tests and reduced the TAT by 25% (12). Fernandes et al. also reported test result differences between blood samples transported manually or by PTS from the emergency department to the laboratory. They did not observe differences in haemoglobin and K+ between the 2 groups. They also observed a significantly reduced laboratory TAT with PTS (13).

Peter et al. observed clinically significant O2 exchange between blood and ambient air during PTS transport, and they discontinued using PTS on samples submitted for blood gas analysis; they installed a blood gas analyser in the intensive care unit (14). Sarı et al. examined the effects of PTS on complete blood count results in blood samples obtained from healthy donors. They observed no effects by PTS on complete blood count parameters. In our study, we also observed no PTS affects on blood cell count parameters, and we observed no differences between manual and PTS modes of transport (15). Liebscher et al. examined the effects of PTS on fresh frozen plasma and erythrocyte concentrates and stated that blood transfusion samples can be transported reliably by PTS (16).

Kratz et al. investigated the effects of PTS and manual transportation on routine haematology and coagulation results and did not observe any differences; however, they observed clinically insignificant but statistically significant results on the mean platelet component and they suggested additional studies to investigate these results. We did not observe any effects on the mean platelet component (17). Wallin et al. investigated the effects of PTS and manual transportation on routine haematology, coagulation, and platelet function with PFA-100, and they did not observe any differences in the results. By thromboelastographic analysis, they observed a shorter duration of clot formation time in blood samples transported by PTS than in those transported manually. They suggested manual transport for blood samples submitted for thromboelastographic analysis (18).

These studies highlight the different results and observations regarding the effects of PTS on medical samples. To the best of our knowledge, no published studies have reported the effects of PTS on blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation, PT, and aPTT in the same study. Thus, we examined the effects of PTS on blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation and several coagulation tests (PT and aPTT). We collected blood samples and transported some by PTS and others manually. We compared results from the tests listed above between the 2 groups. We found no differences in the test results between the 2 groups. In our study, we determined that the PTS used in our hospital imparts no clinically or statistically meaningful effects on routine blood cell counts, PT, aPTT, and erythrocyte sedimentation results. Because every hospital’s PTS will yield potentially unique results depending on the physical conditions of the hospital and the technical properties of the PTS, we concluded that each hospital should evaluate its PTS.

The main limitation in our study was the small number of subjects. Another limitation was related to the absence of TAT measurements in this study. Therefore, future studies should include both a large number of subjects and TAT measurements.

Conclusion

In this study, we have observed that the PTS used in our hospital imparted no significant effects on blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation, PT, or aPTT results. Thus, the PTS in our hospital can be used reliably to transport blood samples without affecting blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation, or several types of coagulation tests. We recommend that all laboratories investigate the effects of their PTS on relevant test results.