Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are among the most prevalent environmental pollutants known to be involved in carcinogenesis (1). These are aromatic hydrocarbons with 3 and more aromatic rings. The best known PAHs are naphthalene, benz(a)pyrene (b[A]P), phenantrene, and anthracite. PAHs mainly result from fossil fuel combustion, as byproducts of industrial processing, human activity, industrial emission, and natural emission (2,3). The main channels through which PAHs enter the environment are coal production and processing, crude oils, natural gases, production of heavy and light metals, and waste incineration.

There are over a hundred of various PAHs, but in practice, only six to sixteen are interesting for analyses and monitoring (4).

Environmental sources of PAH exposure and bioaccumulation

PAHs can be found as air pollutants associated with dust particles, in water, and in the soil and sediments. Air streaming can extend PAHs to large distances and subsequently return them to the soil through precipitation. In the soil, we find them bound to bigger particles, from where some evaporate in the air, while others penetrate into deeper layers contaminating underground water (5). The general population is exposed to PAHs from the environment through small-sized respirable particles, water and food, as well as from the occupational environment (6). The most widespread manner of PAH input is the inhalation of exhaust gases, tobacco smoke, and the usage of products and materials containing PAHs (7). Contrary to popular opinion, alimentary exposure causes a higher rate of human exposure to PAHs than air pollutants do (8). PAH bioaccumulation affects mostly adipose tissue, kidneys, and the liver (9). Smaller amounts may accumulate in the spleen, suprarenal glands, and ovaries. PAHs are excreted in urine or bile in the form of glucoconjugates, sulfoconjugates, and gluthatione-conjugates.

Biomolecular and patho-biochemical effects of PAH exposure in humans

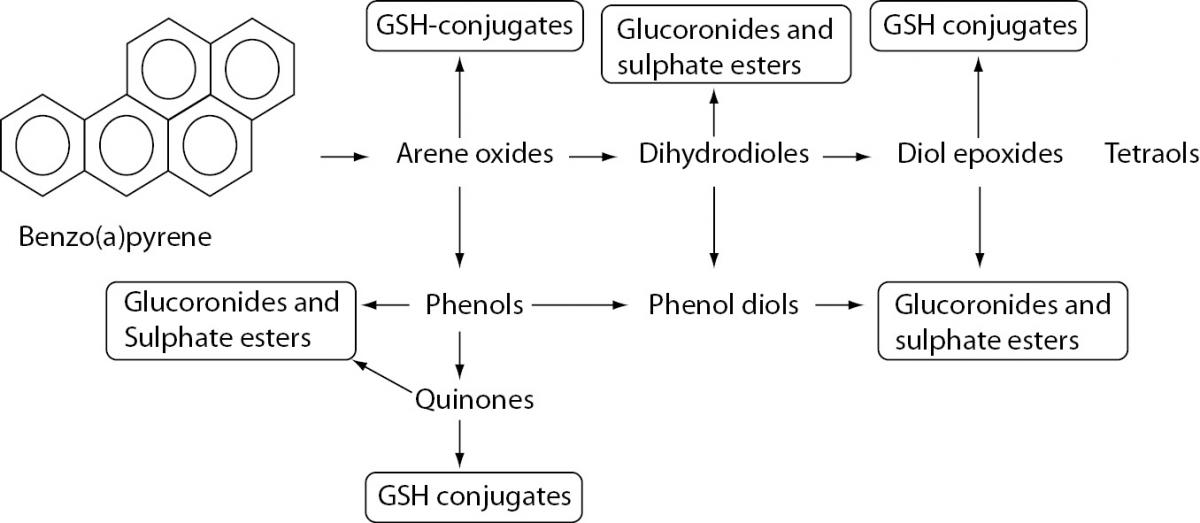

PAHs accumulation may have an effect on human health. These compounds have toxic, mutagenic, and teratogenic effects. The PAH metabolism in the first phase of xenobiotic biotransformation includes cytochrome P450 from the CYP1 family and microsomal epoxide hydrolase, which may lead to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Figure 1). Upon chemically binding to DNA, reactive oxygen species give rise to DNA adducts with very different structures and biological activities (10). Lipids and proteins can also be affected by PAH metabolites. Some subgroups of PAHs and halogenated aromatic hydrogen carbons may even pass the placental barrier (11), which can have a negative impact on fetal cognitive development and cause undesirable consequences to fetal health. PAH exposure also showed to have an important role in atherosclerotic ethiopathology, particularly through the PAH-induced activities of biotransformation enzymes. PAHs from particulate matter (bacterial contaminants, transition elements, salts, and carbonaceous material) may increase monocyte cell adhesion to human aortic endothelia as well as the attenuation of cytokines (12). The variation of genes that encode enzymes involved in PAH-biotransformation may ultimately alter enzyme activity and consequently be involved in the pathobiochemistry of different disorders.

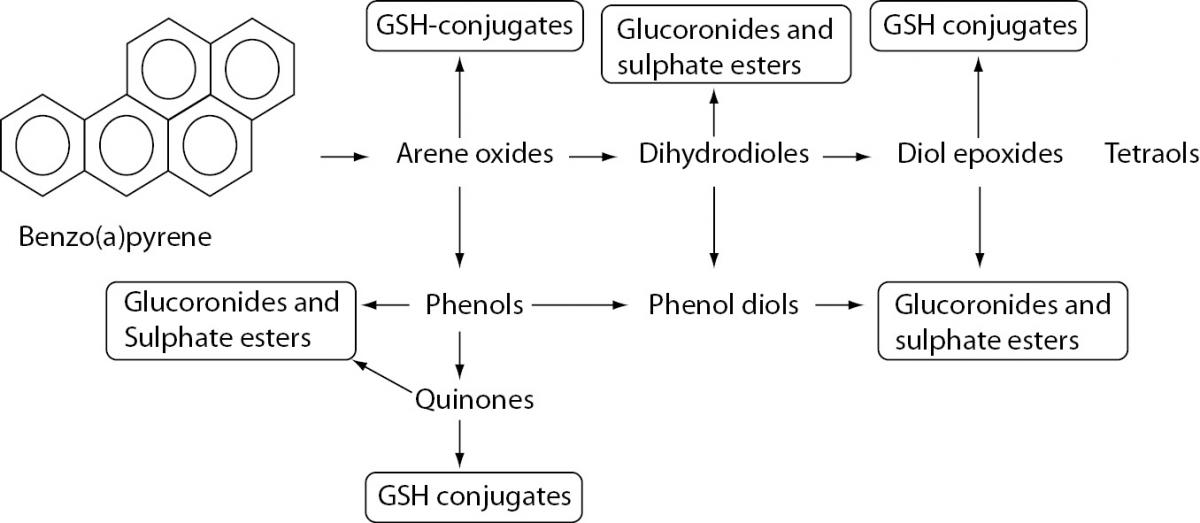

Figure 1. Biotransformation of benzo[A]PYRENE.

PAHs are metabolized in first phase of xenobiotic biotransformation to form several phenols (hydroxy derivatives), phenol diols, dihydrodiols, quinones, and reactive diol-epoxide’s enantiomers. The reactive species are then conjugated to GSH-conjugates glucuronides and sulphate esters to enable better excretion and detoxification of metabolized xenobiotics owing to increased hydrophilicity.

Atherogenesis and PAH exposure

Many sources from the literature have presented the relationships between genetic polymorphisms of gene-encoded enzymes involved in PAH biotransformation and carcinogenesis. The data on atherogenesis are not as abundant.

Atherosclerosis is a process that starts early in a person’s life, but in adults, it is enhanced by various factors. Besides the well-established risk factors involved in atherogenesis (age, sex, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, lack of physical activity and heredity) (13), many other environmental factors contribute to atherogenesis.

The study of interactions between genes and the environment will surely lead to a better understanding of numerous diseases. In this case, exposure to pollutants like PAHs induces specific gene expressions that lead to the biosynthesis of enzymes, which in turn may alter cellular metabolic processes. The diversity of environmental factors and the individual human sensitivity to exposure to these factors may be crucial in the mechanisms responsible for atherogenesis. The polymorphisms of genes that encode enzymes of PAH biotransformation may alter the final specific cellular respond. Thus far, two theories on the mechanisms through which PAHs are involved in atherosclerotic processes have been postulated: 1) formation of DNA-adducts, and 2) involvement of PAHs and its metabolites in the inflammatory processes of atherogenesis (14,15). These theories are mostly based on in vitro and animal model experiments.

A summary of the data obtained in the fields of biotransformation and atherosclerosis as well as of the data on gene polymorphisms involved in biotransformation may provide us with a clearer idea of the interactions between genes and the environment. The general aim of this review is to present the substantial data on PAH exposure as a factor in the development of atherosclerosis. The focus points of this paper include: 1) activation of PAH biotransformation, biotransformation mechanisms, production of specific metabolites that may increase the risk of atherosclerosis; 2) the most frequent genetic polymorphisms of genes involved in PAH biotransformations and atherosclerosis presented in biomedical literature; 3) the influence of certain common genetic variants of genes involved in xenobiotic biotransformations on the development of coronary artery disease (CAD); 4) an overview of different population studies related to the association of common genetic polymorphisms and atherosclerosis; and 5) gene–environment mechanisms involved in the process of atherosclerosis development.

PAH biotransformation

The function of the receptor aryl hydrocarbon (AhR)

PAHs such as (B(a)P) are known as potent ligands of AhR. These molecules are mediators for increasing intracellular calcium concentrations(16). AhR recognizes a large number of xenobiotics, such as PAHs and dioxins, and activates several metabolic and detoxification pathways (17). AhR acts as transcriptional factor and mediates intracellular response through regulating genetic expression. AhR induces cytochrome P450 (Cyp)1a1 expression, which corresponds well with the induction of apoptosis and mutagenesis (18).After entering into the cell, PAHs bind to the AhR and the complex PAH-AhR is translocated into the nucleus. The expression of the CYP1A1 gene is enhanced by the xenobiotic responsive element (XRE) from the promoter region of the CYP1A1 gene, the aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator (ARNT), the xenobiotic responsive element (XRE) and AhR (19,20).

PAHs are metabolized in enzymatic reactions catalyzed by several different enzymes, including cytochrome P450 (CYP), epoxyde hydrolase (EPH), glutathione transferase (GST), UDP-glucuronosyl transferase (UGT), and sulfotransferase (SULT) (21).

First phase of PAH metabolism

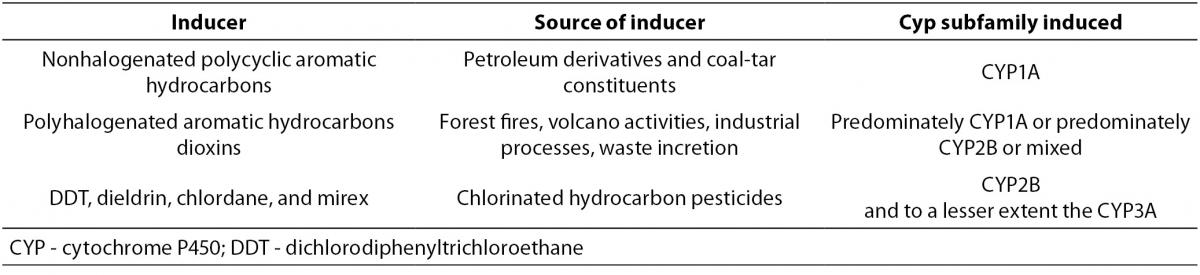

The most abundant isoforms of CYP induced by non-halogenated PAHs are those from the CYP1A subfamily (22). Specific CYP families may be induced by different chemicals as presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Different CYP families induced by different chemical inducers (19).

After exposure, PAHs are metabolized to form several phenols (hydroxy derivatives), dihydrodiols, quinones, and reactive diol-epoxide enantiomers (Figure 1) that have the capacity to bind DNA and form PAH–DNA adducts (1,23).

Second phase of PAH metabolism

Covalent additions of sugars, amino acids and peptides, as endogenous ligands, are the major reactions involved in the second phase of xenobiotic transformation (24).

The enzymes from different superfamilies enable conjugation (e.g., with glutathione or glucuronic acid). Several polar compounds are produced and thereby the excretion of chemicals is facilitated by the formation of products with more polar groups. Enzyme superfamilies involved in conjugation reactions are different transferases like SULT, UGT, GST, and N-acetyltransferases (NAT) (25,26). Beside transferases, oxidoreductases NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO) and NAD(P)H: menadione reductase (NMO), hydrolases such as EPH are also involved in the second phase of the xenobiotic metabolism (25,26). The gene expression of drug metabolizing enzyme (DMEs) genes provides the various isoforms of the enzymes with different induction and leads to inhibition by xenobiotics, different substrate specificity, and different expression (27). Conjugation with DMEs in the second phase of xenobiotic metabolism enables better excretion and detoxification of metabolized xenobiotics owing to increased hydrophilicity (28). Sometimes, the second phase produces activated metabolites with increased toxicity (29). The expression of the second phase can be induced by numerous structurally unrelated chemicals.

Human GSTs in the second phase of the PAH metabolism

Human GSTs are divided into three main families: cytosolic, mitochondrial, and membrane-bound microsomal (30). The cytosolic GST (cGSTs) superfamily, which exists predominantly in the liver but is also widely distributed into various tissues, encompasses a number of isoenzymes. Glutathione is a cytosolic nucleophilic tripeptide that conjugates epoxides and other reactive intermediates via GSTs and is used in the prevention of oxidative stress (31). Oxidative stress is well-known to be the basis of atherosclerotic pathology.

cGSTs alpha (GSTA), mu (GSTM), pi (GSTP), sigma (GSTS), omega (GSTO), zeta (GSTZ) and theta (GSTT) are the most ubiquitous isoforms(32). Isoenzymes are grouped according to substrate specificity, amino acid sequence, and immunological cross-reactivity (30).

CYP1A1 and GSTs µ and θ as major factors in PAH-biotransformations and their influence on atherogenesis

CYP1A1 and atherogenesis

The enzyme CYP1A1, which is encoded by the CYP1A1 gene, is the most important in the monooxygenation of lipofilic substrates such as PAHs. The most common PAH, as a substrate for CYP1A1 in this subgroup, is B(a)P, a carcinogen compound found in tobacco smoke (33). As one of the main enzymes for detoxification, CYP1A1 is involved in the mechanisms of carcinogenesis and atherogenesis induced by PAHs from cigarette smoke (34).

There are at least two theories that explain the involvement of PAHs in atherogenesis. PAH-DNA adducts are known to cause DNA mutations involved in carcinogenesis. It is hypothesized that there is an interrelationship between PAH exposure and PAH-DNA adducts in aortae. Chemically induced arterial DNA damage may induce mutations that lead to cellular transformations into proliferative clones (14).

On the other hand, the inflammatory atherosclerotic plaque phenotype can be induced by PAHs independently of the formation of their DNA-adducts. A study performed on an animal model of apoE-KO mice clearly demonstrated this (15).

In vitro examination showed that CYP1A1 activates PAHs. The suppression of LXR-mediated (liver X-receptor) signal transductions ensures PAHs direct involvement in atherosclerotic processes (35). LXR are ligand-gated transcriptional factors that belong to a superfamily of nuclear receptors. These receptors act as key regulators of lipid metabolism and inflammation (36). The regulation of the lipid metabolism by LXR is provided by the regulation of intestinal cholesterol absorption through the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) gene family (37). On the other hand, the regulation of inflammatory events is evident from an animal model experiment which showed that B[a]P induces monocyte chemo-attractant protein (MCP-1) gene expression in the aortic tissue of ApoE-/- mice (38). Monocytes travel to damaged areas (atherosclerotic lesions) facilitated by MCP-1. In addition, CYP1A1 is also involved in the production of the arachidonic acid-derived vasoactive substance which also may be involved in proinflammatory processes (39).

GSTM1 and GSTT1 convert electrophilic products of the first phase of PAH biotransformation

GSTM1 and GSTT1 are enzymes from the human cytosolic GSTs superfamily, which contains 8 distinct classes (40). These two enzymes are encoded by the GSTM and GSTT genes, respectively. The main role of GSTM1 lies in the detoxification of electrophilic xenobiotics such as benzopyrene diol-epoxide, the products of CYP1A1, as well as other xenobiotic and environmental pollutants (41). The main role of the GSTT1 isoform is the conjugation of oxidized lipids and halogenated compounds. The safe removal of toxins by conjugation with glutathione saves cells from oxidative damage and DNA mutation, potentially altering the rate of cellular sensibility. However, recent findings have shown that GSTs may act via non-enzymatic pathways and be involved in cell signaling through MAP kinase, which includes DNA damage signaling (42).

Mapping CYP1A1, GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes and their common genetic variants

CYP1A1 gene

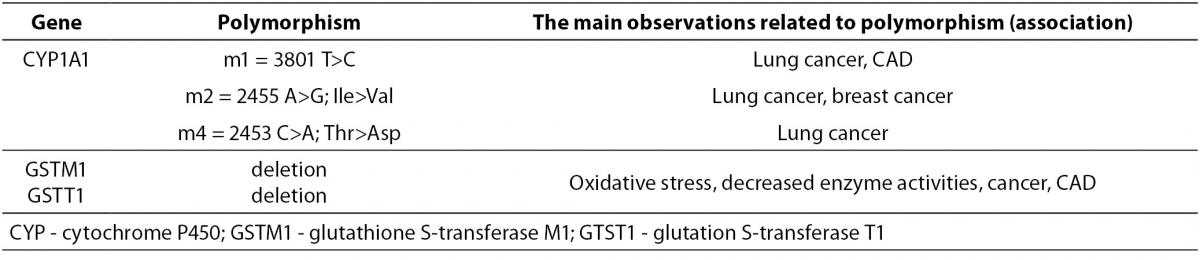

The human gene CYP1A1 locus has been mapped on chromosome 15q24.1, which is composed of 7 exons (43). Several common genetic polymorphisms of the CYP1A1 gene (Table 2) have been described in the literature and designated as m1, m2 m3 and m4. The polymorphism Cyp1A1-Msp I or m1 represents 3801 T>C substitution in the 3’ non-coding region of the CYP1A1 gene (rs4646903), which determines translation and mRNA stability (43,44). Nucleotide substitution 2455 A>G (m2) results in amino acid substitution, Ile462Val (rs1048943) (44). The m3 variant symbolizes nucleotide substitution 3205 T>C in intron 7 (rs4986883) (43,45), while nucleotide substitution 42453 C>A represents variant m4, which results in the amino acid substitution Thr>Asp, (rs1799814) (46). Investigations of CYP1A1 gene polymorphisms mostly indicated their causal role in carcinogenesis, while data on the association between polymorphisms and atherogenesis are lacking. The CYP1A1-Msp I genetic polymorphism is mostly presented in the literature as an enhancer of human predisposition to CAD.

Table 2. The most common CYP1A1, GSTM, and GSTT polymorphisms.

GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes

The GSTM1 and GSTT1 loci have been mapped on chromosome 1p13.3 and 22q11.2, respectively. μ (GSTM1) and θ (GSTT1), as members of the GST family, most commonly exhibit deletion polymorphisms (Table 2). The complete deletion of the gene (homozygotes) is a consequence of the absolute absence of both alleles (‘null’ alleles- GSTM1*0 or GSTT1*0), which results in a deficit of enzyme activity. Heterozygotes with only one ‘null’ allele usually have reduced enzyme activity (47-49).

As GSTT1 and GSTM1 play a role in the deactivation of reactive oxygen species, which are involved in cellular inflammation and degenerative disorders, it has been shown that polymorphic isoforms with reduced enzyme activity might contribute to these processes in the cell (50). Genetic polymorphisms can increase or decrease the sensibility of an organism to cancerogenesis and the inflammatory processes involved in the development of atherosclerosis (30).

The influence of CYP1A1, GSTM1 and GSTT1 genetic variants on the development of CAD

An overview of population studies

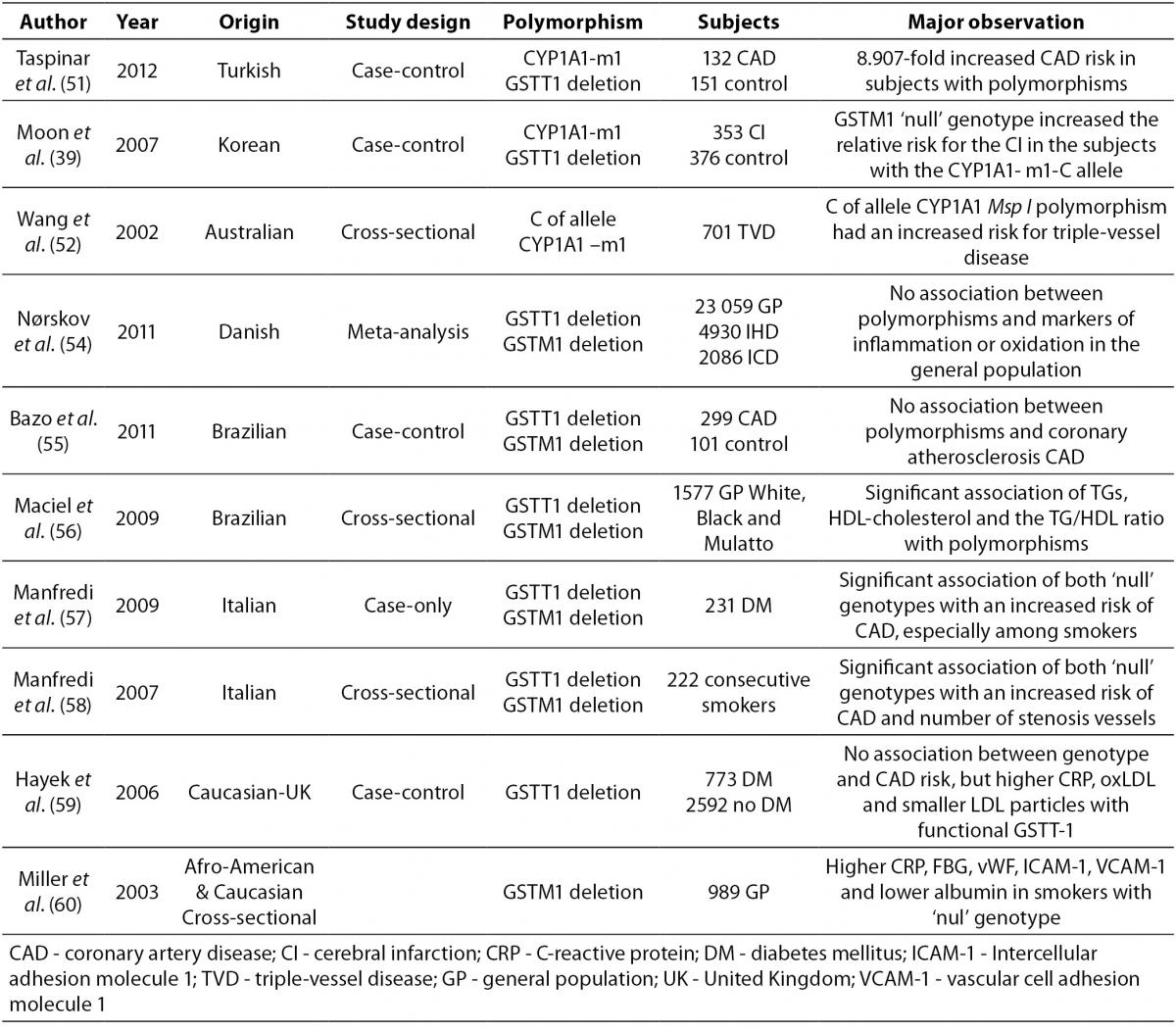

Data on the association of atherosclerosis and CYP1A1, GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms are lacking and controversial due to aspects such as study design, population, and number of subjects examined. Several case–control studies have observed the association between the genetic polymorphisms CYP1A1, GSTT1 and GSTM1 and CAD. An overview of these studies is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. An overview of different population studies related to association of common CYP1A1 and GST genetic polymorphisms with CAD.

A very high predisposition for CAD was observed in Turkish CAD patients in comparison to healthy controls with the CYP1A1-m1 variant and GSTT1‘null’ genotypes after adjustment for risk factors (51).

An association between the CYP1A1-m1 variant and cerebral infarction (CI) was found between case and control Korean subjects (with or without cerebral infarction). Increased relative risk for CI was observed in individuals with the CYP1A1-m1 variant and GSTM1‘null’ genotype. (39).

The CYP1A1-m1 variant was also shown in Australian subjects as a significant factor for increasing the risk of triple-vessel disease (three major epicardial coronary arteries with 50% luminal obstruction) in light smokers. This relation was not present in heavy smokers probably due to excessive toxic exposure, which makes genetic effects irrelevant (52,53).

A meta-analysis in Denmark, which included subjects from general population studies and case-control studies with case subjects suffering from ischemic heart disease and ischemic cerebrovascular disease, did not show an association between the GSTT1 and GSTM1 genotypes and markers of inflammation or oxidation (54).

Two Brazilian studies investigated the association of GSTM1 GSTT1 polymorphisms, CAD, and plasma lipid parameters (55,56). There was no association with CAD in the first case-control study (55), while a significant association was observed for lipid parameters and genotype distribution of GSTM1 and GSTT1 deleted deletion polymorphisms in patients who underwent coronary angiography (56).

Two studies performed on Italian subjects who underwent coronary angiography showed an association between GST polymorphisms and CAD in smokers (57,58). Type 2 diabetes patients who smoked had a significantly higher risk of suffering from CAD if they were carriers of GSTM1 and GSTT1’null’ genotypes (59). Consecutive smokers with combined GSTM1’null’GSTT1’null’ genotypes also had a higher risk of CAD and significantly higher number of stenosis vessels, after adjustment for risk factors (58). A case control study that included Caucasian subjects with diabetes and non-diabetics showed no association between the GSTT 1 genotype and CAD risk (59).Indeed, diabetics with functional GSTT1 had higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and oxidated-LDL (Ox-LDL) as well as smaller LDL particles when compared to GSTT1’null’ individuals, while smokers with functional GSTT-1 had a higher CAD risk when compared to non-smokers (59).

The highest mean levels of CRP, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 as well as the lowest mean levels of albumin were observed in a cross-sectional study performed on a biracial cohort (African-American and Caucasian), in subjects with the GSTM1 ‘null’ genotype who smoked a pack of cigarettes per day for 20 years (60).

Limiting data aside, it is clear that GSTM1 and GSTT1 deletion polymorphisms alter the effect of smoking on endothelial function, as well as the processes of inflammation and hemostasis (60).

The association between GST polymorphisms and alterations in lipid concentrations

Although peculiar, the association between GST polymorphisms and lipid concentrations can be explained. Maciel et al. (56) hypothesized that GTSs are responsible for hypertriglyceridemia and decrease of HDL-cholesterol plasma concentrations by inhibiting the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-y (PPARy). This is due to the role of GST activity in the formation of prostaglandin J 12 (PgJ12)-glutathione conjugate responsible for PgJ12 activation of PPAR-y dependent transcription (56). The formation of this conjugate is thereby involved in the sequestering of the ligands in the cytosol away from their nuclear target - PPARy. The conjugation of PgJ12 disables the PPAR-y regulation of fatty acid metabolism and therefore attenuates the favorable effects of PPAR-y on lipoprotein metabolism, adipocyte function, insulin sensitivity, and vascular structure (61).

Interaction of other atherosclerosis risk factors with genetic polymorphisms of enzymes involved in the biotransformation of PAH

In the environment, PAHs are biologically inert. In the human organism, they induce enzyme activities which convert them into reactive intermediates. Therefore environmental exposure to PAHs negatively impacts human health. As mentioned previously, it is evident that the literature data on the genetic polymorphisms of CYP1A1, GSTT1, and GSTM1 demonstrated a relationship between these polymorphisms and smoking and the development of malignant diseases and atherosclerosis. The main substrates for the biotransformation by enzymes mentioned earlier are PAHs from cigarette smoke and their metabolites (62). Cigarette smoking causes DNA alterations in the heart and blood vessels, which leads to the development of CAD. The individual variability of CAD development in cigarette smokers results from the genetic polymorphisms of enzymes involved in the xenobiotic metabolism (58). It has also been proven that several genetic variants interact with smoking to increase lipid peroxidation, thus providing an even stronger atherogenic effect (59).

Apart from cigarette smoke, PAHs can be found in crude oil, natural gases, during the production of heavy and light metals, waste incineration, etc. Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene (1-HP) was used as a biomarker of occupational and environmental PAH exposure in several studies. A review of studies conducted on Taiwanese and Chinese workers in the petrochemical industry showed the highest concentrations of urinary 1-HP in coke-oven workers (63).Exposure of city policemen to the city air in downtown Prague induced genetic damage and increased DNA adducts even in non-smokers (64). Some human studies showed that survival depends not only on traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis, but also on the molecular endpoint, genetic polymorphisms, and their combinations (65).

For example, subjects with double ‘null’ GSTM1/GSTT1 polymorphisms are more susceptible to the development of atherosclerosis, while smoking significantly increases the number of stenosis vessels in subjects with a positive genotype. On the contrary, the association of GSTM1 deletion and molecular damage in atherosclerosis depends on different factors and includes other polymorphisms (gene-gene interactions), life style habits, and the influence of the environment (58,66).

In general, the overview of population studies has shown that CYP 1A1-Msp I polymorphisms and the deletion polymorphisms of GSTT1 andGSTM1 may be involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disorders, especially when combined with other risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, environmental exposure factors, and habitual factors such as cigarette smoke.

It is well-known that genetic susceptibility contributes to the pathogenic pathways that lead to atherogenesis and other multifactorial disorders. The genetic polymorphisms of genes involved in PAH biotransformations evidently bring forth a risk of disease development. Thus, occupational exposure or conditions from one’s living environment and habits can contribute to the production of PAH metabolites with adverse effects on human health. Investigations aimed at the effect of the gene-smoking allow for a better understanding of gene-environment interactions. They should ultimately lead to the creation of a personalized medicine concept regarding cardiovascular diseases (58,66).

We may conclude that prevention and early intervention could be enhanced by data on genetically susceptible individuals. Also, the elucidation of genetic factors and their association with environmental influences might prove useful for treating high-risk patients with the aim to reduce their risks for atherosclerotic events.