Low level of adherence to instructions for 24-hour urine collection among hospital outpatients

Marijana Miler

[*]

[1]

Ana-Maria Šimundić

[1]

Introduction

Excretion of certain analytes might vary during the day and for such analytes timed urine collection is required. Timed urine collection (e.g. 24-hour collection) is susceptible to many preanalytical errors, which have consequently influence on laboratory results and can lead to misdiagnosis and improper therapy. The most common error is failure to collect the entire urine volume during 24 hours or collecting the excess of sample. For example, creatinine clearance could be falsely decreased if 24-hour urine sample was not completely and properly collected (1). One of the preanalytical errors could also be a loss of specimen from poorly sealed container. Urine specimen should be stored in refrigerator during collection and allowed to come to room temperature before testing in order to reduce false results in enzymatic reactions, which depend on temperature. Preanalytical error in collecting 24-hour urine specimen is using container with preservatives. Improper storage at room temperature or collecting urine sample in container with preservatives could also lead to incorrect creatinine clearance results (2).

Timed 24-hour urine specimen collection should start at any time in the morning, after discarding first morning urine sample in the toilet. After that, entire volume of urine should be collected in the clean, unused container with 2-3 L volume (3). According to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (former National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, NCCLS) guidelines, laboratory staff should organize continuous education of clinicians and patients to ensure proper collection procedure and sample of high quality. Physicians and laboratory staff should inform patients about proper collection of 24-hour urine specimen according to available guidelines (2). Outpatients are usually poorly informed about adequate timed urine collection and are not aware of importance of proper urine sample collection.

In our outpatients ambulance leaflets with 24-hour urine collection guidelines are available. In addition, procedure with proper steps for collecting urine is easily accessible on the laboratory official webpage. Despite that, we assume that patients are not well enough informed about proper procedure for urine collection and its relevance in determination of biochemical analytes.

The aim of this study was to assess how well are outpatients informed about procedure of 24-hour urine specimen collection.

Materials and methods

We have done our survey in outpatient laboratory of University Department of Chemistry, Medical School University Hospital Sestre Milosrdnice, Zagreb, Croatia. The survey was done during 12-days period, at the end of November and at the beginning of December 2012. We have asked randomly chosen outpatients with collected 24-hour urine sample to answer the questionnaire with 10 questions. If they have consented to participate in the survey, they were included in the study. Patients who refuse to answer the questionnaire were not included or persuaded to participate in the survey. The questionnaire was anonymous and that was emphasized to patient before the survey.

Results

Total of 59 patients were included in the study, out of which 38 were females. Almost all participants were older than 40 years (N = 57), with half of them older than 65 years. Our patients were not using Internet as a source of information and only one has visited the official webpage of University Department of Chemistry, which holds crucial information about collection procedure.

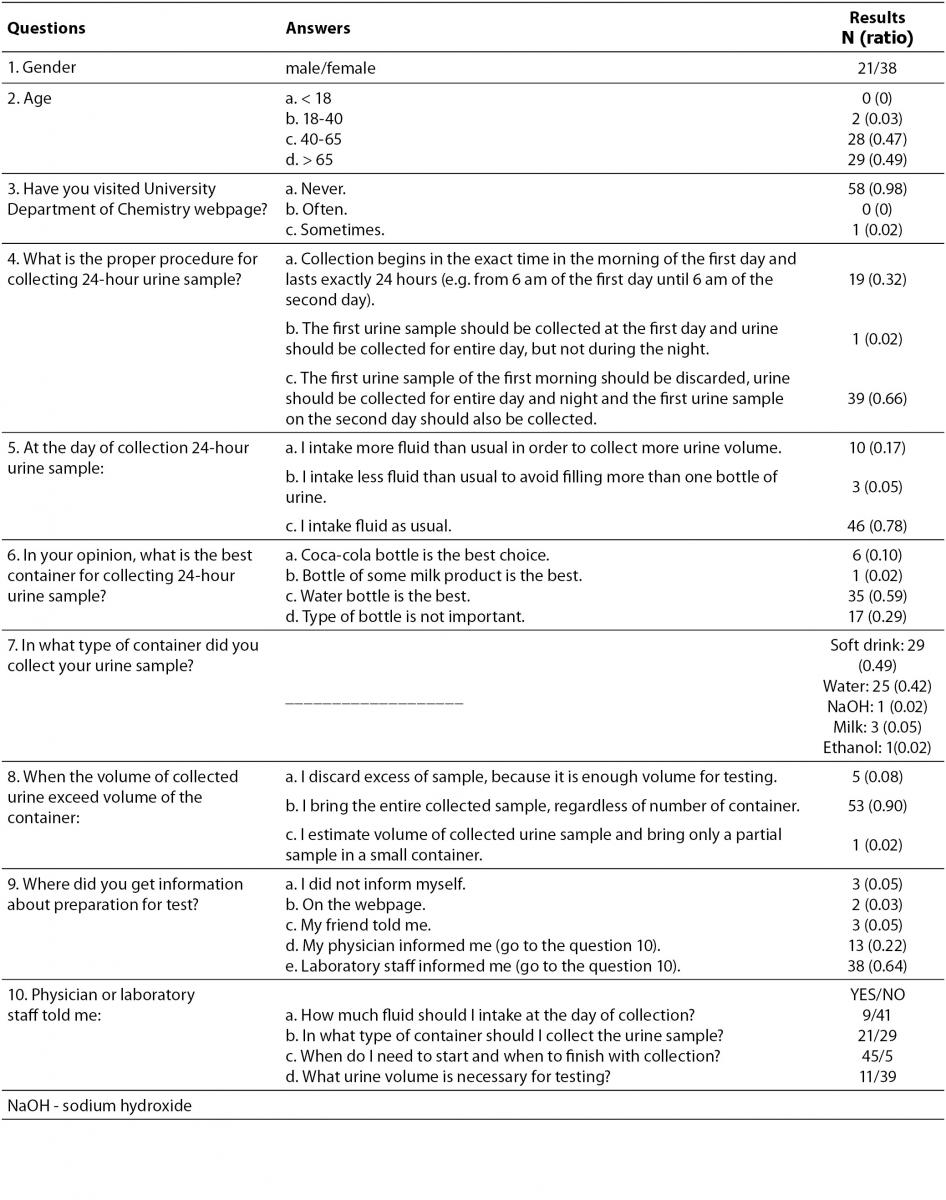

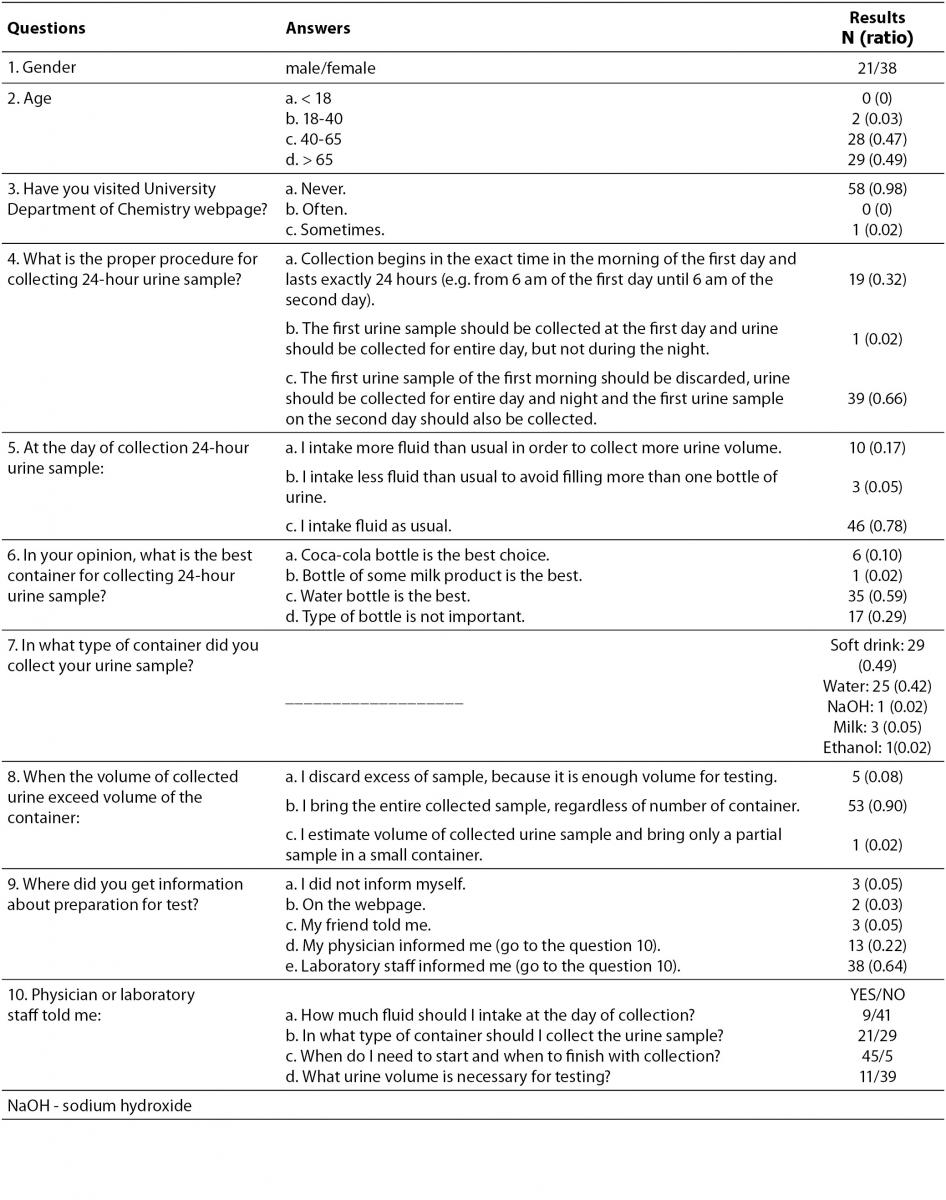

One fifth of patients have purposely increased fluid intake on the day of urine collection in order to collect more urine volume. Most of the patients were aware that the water bottle is the best choice for the urine container. Despite that, half of the patients collected their sample in the plastic bottle that previously contained soft drink (e.g. Coca-cola bottle). Three patients even collected their urine sample in the plastic bottle of milk. Surprisingly, two patients collected their samples in bottles that have previously contained ethanol and sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Even one in ten patients brought only a portion of collected sample and not entire volume. The majority of patients stated that they were informed about proper 24-hour urine sample collection procedure by the laboratory staff and physicians. Nevertheless, most of the patients answered that laboratory staff and physicians have not informed them about amount of fluid they should intake on the day of collection, nor in what type of the container they should collect urine sample, nor what urine volume is necessary for testing. All results and ratios are shown in the table 1.

Table 1. Survey questions with offered answers and results.

Discussion

Participants of our survey with collected 24-hour urine specimen are mostly older patients which are in general poorly informed about proper 24-hour urine collection. Even when they were informed by their physicians or laboratory staff, patients were not collecting their samples according to guidelines.

Although majority of patients (0.85) were informed about correct collection procedure by laboratory staff or physicians and written guidelines were available to all outpatients in laboratory ambulance, more than half of the outpatients did not collect their 24-hour urine sample properly. They used an improper container, discarded some of their sample or did not follow instructions for collection timing. Patients did not take much care about the importance of proper urine collection.

Our laboratory has official webpage with all relevant information for patients, including preparing for blood and urine testing (4). Only one patient has visited the webpage to inform herself about specific procedure of 24-hour urine collection. The reason for such a low rate of webpage visit could be the age of patients which are mostly older than 65 years. Since most of the patients suffer from some chronic disease (osteoporosis, chronic kidney failure, diabetes mellitus type 2) they assume that they know everything there is to know about their disease and believe they do not need any more information.

According to CLSI guidelines, collection of 24-hour urine specimen should begin in the morning, at a specific time by discarding the first urine in the toilet. After that, entire collected urine volume should be placed in the proper collection container. Container should be original, clean, plastic, not reused and at least 3 L in volume. In the guidelines is even stated that nurse or patient should be instructed to collect all voided urine and simple description of procedure should be written and available to patients (2).

In addition, in the moment of specimen reception, laboratory staff should ask every patient about collection procedure. If the collection was not according to the guidelines, the sample should be rejected and patient should repeat the collection. In our experience (by watching laboratory staff during patients admission), only a small number of laboratory technicians asked patients how the specimen was collected.

The reasons for testing and instructions for proper collection should be provided to all patients. Collection procedure should be described in oral and paper form for better understanding of the process (5). Patients are generally not well informed and feel powerless in controlling of their health. This happens because physicians do not have enough time for explaining all medical treatment, especially to chronically ill patients and they think that patients are not interested in details about all tests and procedures (6). It is interesting that all patients who have discarded some volume of collected urine sample claimed that they were informed by their physicians.

On the official webpage of University Department of Chemistry and on the official leaflet available in the ambulance, it is stated that 24-hour urine specimen should be collected in a clean plastic bottle of still mineral water. In our survey, half of the patients have collected urine specimen in some kind of soft drink bottle and only every third patient in the water bottle. Three patients even collected their urine samples in the milk bottles. Interestingly, 2 out of those 3 patients were tested for calcium concentration in urine.

The usage of improper container could be reduced if the laboratory would provide a proper collection bottle for each patient. However, at this moment it would cost a substantial amount of money and would demand restructuring of the current health system.

Limitation of this survey is small number of patients. Also, question 4 could be misleading due to overlapping answers a) and c).

Despite the fact that only 59 participants were surveyed, we can notice that patients are not well enough informed. Laboratory staff should also be more active in promoting preanalytical procedures in order to reduce errors in analytical phase. Tormo et al. have proven that after education and training of physicians and other health care staff, the percentage of preanalytical errors in timed urine collection was reduced (7).

Communication between laboratory and general practitioners should be improved. Leaflets and other information should be available already in physician’s ambulance. When patients come to laboratory, it is often too late to correct previous collection procedure. Laboratory staff is usually not aware of patients improper urine collection. In the laboratory ambulance, staff should also be educated in asking right questions and to reject improper collected specimens, in order to avoid result errors.

Conclusion

Patients are usually not aware of the importance of proper preanalytical procedure for collecting urine specimen and how improper collection could affect test results. Education of outpatients, general practitioners and laboratory staff is needed in order to improve sample quality and trueness of results.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Ministry of Science, Education and Sports, Republic of Croatia, project number: 134-1340227-0200.

Notes

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Nankivell BJ. Creatinine clearance and the assessment of renal function. Aust Prescr 2001;24:15-7.

2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Urinalysis and Collection, Transportation, and Preservation of Urine Specimens; Approved Guideline-Second Edition. NCCLS GP-16A2, Volume 21, No. 19. NCCLS, Wayne, Pennsylvania, USA, 2001.

3. Kouri T, Gant V, Fogazzi G, Hofmann W, Hallander H, Guder WG, Eds. European Confederation of Laboratory Medicine (ECLM). European urinalysis guidelines. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2000;60(Suppl 231):1–96.

6. Eurobarometer Qualitative Study. Patient involvement, Aggregate Report. May 2012.

7. Tormo C, Lumbreras B, Santos A, Romero L, Conca M. Strategies for improving the collection of 24-hour urine for analysis in the clinical laboratory: redesigned instructions, opinion surveys, and application of reference change value to micturition. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009;133:1954-60.