Disclaimer

I‘d like to start this opinion piece with a disclaimer – I am going to do something not entirely common in a scientific journal, and NOT cite those articles I mention in this manuscript! That is, I will not disclose the titles nor cite the articles that have been retracted or are being investigated for possible fraud. I however, may mention the journals that published them or key name(s) from the byline in the text. The reason behind this endeavour (beside the fact that there are so many of these articles) is simple, albeit verbose – the retracted articles do not die, but rather receive citations years and decades after their retraction (1,2), often by the authors themselves (3), the web-pages where the articles are presented are accessible directly from the journals they were supposedly retracted from or indirectly from non-publisher sources (4). The extended life of citations happens in spite of the journal editors’ best efforts, or even maybe even because of them, if their efforts to explain the retraction are vague or inconsistent (5). So, in order to stop promoting possible citations of retracted or soon-to-be-retracted articles, allow me not to cite them.

Corrections and retractions in scientific journals

Corrections and retractions are an integral part of scientific publication because they constitute what can be described as the scientific method and ethical publishing – the burden of evidence dictates that what was thought to be right, or what was purported to be right has to yield to what is evidently right, and, hence, needs to be corrected in the public domain’s record keeping. Most of the burden of keeping the record straight eventually falls onto the journal editors’ backs (6), and, although the editors are not the scientific community’s policemen (7), they have responsibilities and roles, as well as tools at their disposal. These are best defined by the Council of Editors’ White paper on Publication ethics (8), which notes that editors can correct the public record by publishing either corrections (errata or corrigenda), which “identify a correction to a small, isolated portion of an otherwise reliable article” or retractions, that “refer to an article in its entirety that is the result of pervasive error, nonreproducible research, scientific misconduct, or duplicate publication”. Within an editor’s toolbox are, also, expressions of concern that draw the attention of the public to possible problems in a published article, without, actually, correcting or retracting it (8). Once published, these corrections, retractions, and expressions of concern become “notices”.

The total number of these notices in recent years (9), mostly as a result of increased rates of retraction (10), has made us acutely aware of the retraction epidemic. How many retractions? Some thirty plus years ago, there were very few retractions – on the order of 1 or 2 retractions per year. In the 1990ies, the number rose to approximately 1 or 2 a month (i.e. 10-20 per year). By the late 2000s it rose to 1 a day (around 300 per year), and in the last couple of years it has risen to approximately 2 retractions every 3 days or around 500 per year (9,11,12). While the frequency of corrections has been constant throughout the various scientific fields (11), the frequency of retracted publications has dramatically increased even after correcting for the increase in total scientific publication output (9), while at the same time the “time-to-retraction” has significantly decreased (13). A possible explanation of this trend may be an increased awareness of editors of these issues and their (increased) willingness to retract rather than (significantly) correct a manuscript. Whether the reasons for most retractions are fraudulent results begotten of research misconduct (9,14), or not (15), and whether there is an increase in plagiarism and duplicate publications (16) still needs to be ascertained, but the evidence-based understanding of the problem may be skewed by the journals’ retraction practices and the (ambiguous) wording of the retractions (5).

One can argue that most retractions happen because of the comments from interested readers (the scientific community), aptly called by Cokol et al. the “post-publication scrutiny” (17). Following their algorithms, it is obvious that journals with a higher impact factor (IF) have a bigger and more scrutinizing readership than the journals with a lower IF. It is appealing to call this post-publication scrutiny “self-correction” of biomedicine (16), but also somewhat misleading, as it is indeed biomedicine that is doing the corrections, and not necessarily the authors who transgressed.There are of course other, more sinister, explanations for the increase in retractions, such as the possibility that the number of authors ready to commit scientific misconduct or abuse publication ethics is on the rise. It just as well may be that the overall decay of the moral fabric of society in general is mirrored in the retractions. Those explanations are, however, difficult to confirm, as there is preciously little research on the topics, and the research that does exist is skewed by the existence of researchers with multiple retractions (15), and (under?)reported rates of misconduct (18,19). Unfortunately, the depressing take home message is, also, that it is safe to assume that the fraudulent research far outweighs the research that is retracted (18).

The stigma of correction and retraction

Every correction and retraction is a source of embarrassment for all involved – the author(s), the journal, the editors and the reviewers. Ideally, a correction is minor and the journal is prompted to correct by the author(s) who published the original result (usually because the building upon those results was unsuccessful). Less ideally, the author(s) recognize there was a serious mix-up (unintentional, hopefully), and the results “really” do not add up. Then, however difficult and stressful it may be, all the authors should contact the editors and ask for a retraction disclosing everything that went wrong. Did I say disclosing everything? Yes. Total transparency is key to maintaining face and credibility. From this, “less ideal” scenario, there are many ways the situation can get worse. Worst case scenario? An external “force” (the post-publication scrutinizer) complains to the editors and the public about the veracity of the data published, the authors refuse to take responsibility, make all kinds of unsupported claims defying the overwhelming facts, fight the accusations by lashing blindly at everyone with all they’ve got. Nevertheless, the retraction still happens, and the authors are left marred by the experience for the remainder of their fizzling career.

Authors with multiple retractions

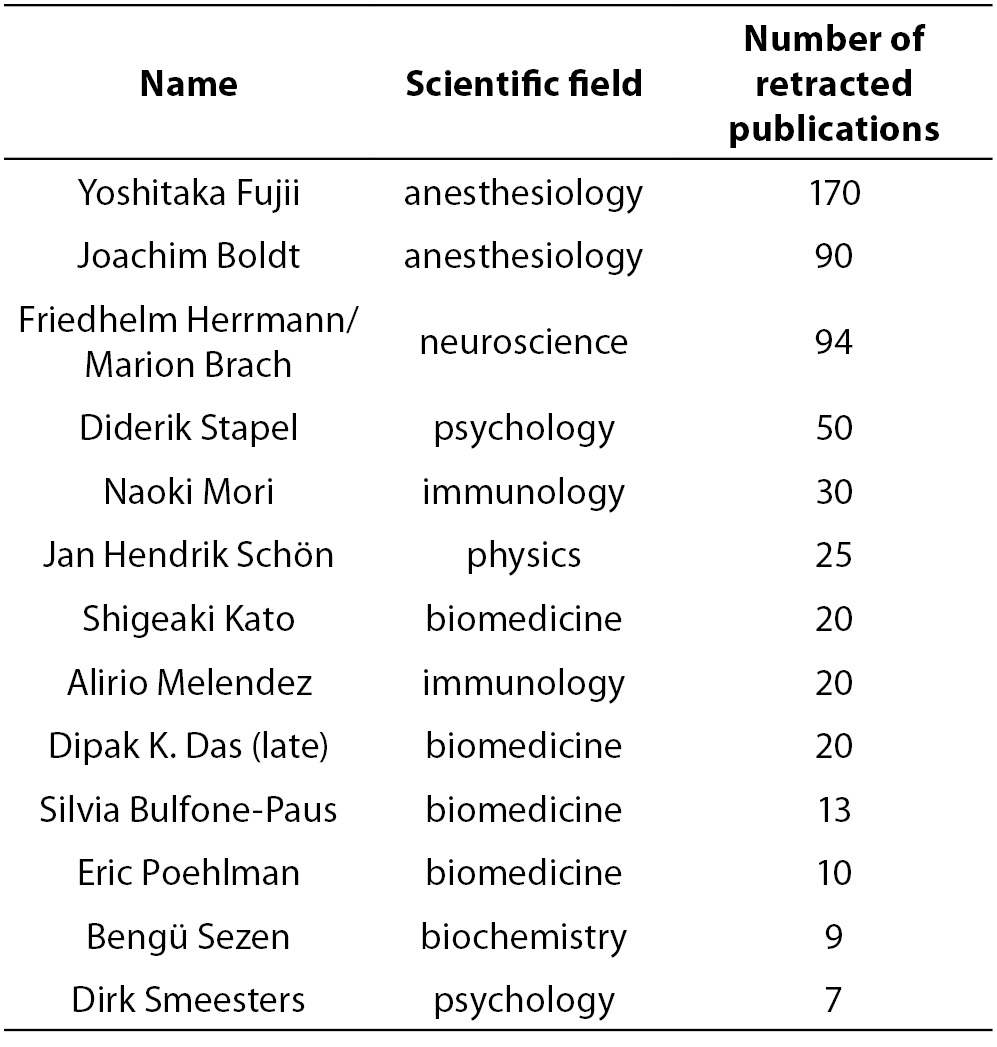

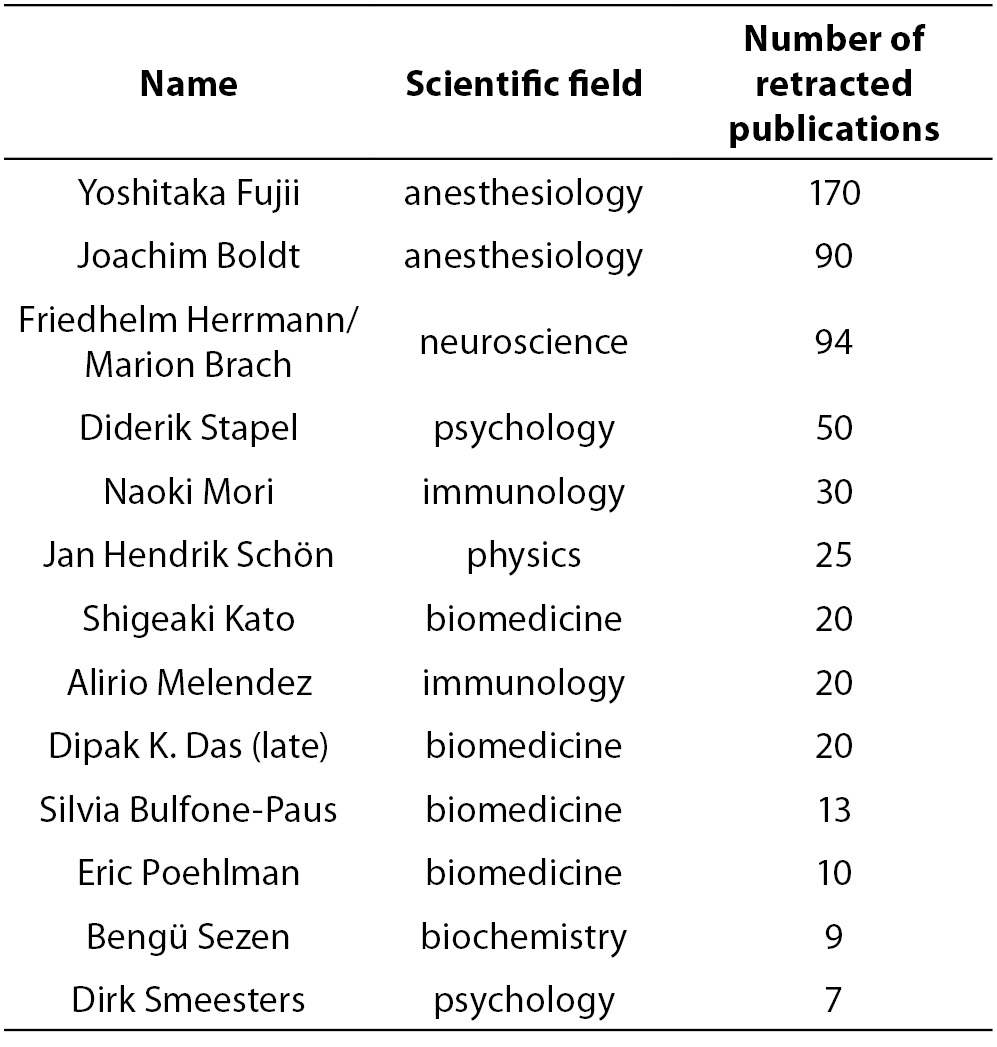

The surprising thing in the analyses of retracted publications is the number of researchers with multiple retracted publications and the number of retracted publications (or publications found to be fraudulent that are awaiting retraction) they published (15). Some of these “authors” are presented in Table 1. With a few exceptions, most of them refused to take responsibility for their actions and failed to acquiesce to what they had done. This list is, unfortunately, far from complete, and would have been quite difficult to assemble were it not for the efforts of the bloggers at Retraction Watch (12), an on-line community of researchers frustrated with the science’s (not the journal!) inability to timely, publicly, and efficiently self-correct.

Table 1. Some authors with multiple retractions from the last decade.

Journals of “choice”

While the (high) number of retracted publications (both total and per “retractor” or maybe better “retractee”) may be shocking, it is interesting to note that many of the “authors” consistently make high impact, high visibility, (and high risk) career/publication choices. It may seem that the journals with a high IF attract a disproportionate number of research publications that end up retracted. The exact understanding as to why and the algorithmic predictive modelling differs between researchers (17,20). I surmise that, apparently, the fraudsters (having already performed misconduct in their research) go “all in”, and (try to) publish in journals most likely to afford them, however short-lived, international prestige and visibility [or as the fraudsters might erroneously think – fame, fortune, and love of (wo)men].

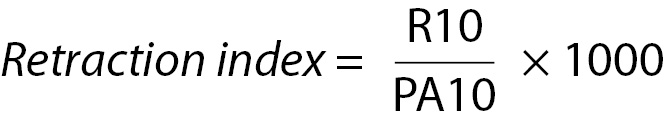

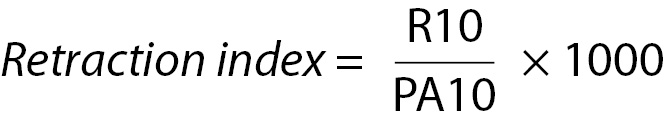

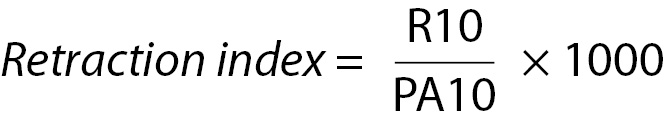

As is often the case, one learns best from one’s own experience, so it wasn’t until the “efforts” of Naoki Mori to publish his research articles in Infection and Immunity (6 of which were published and retracted in a single year), and the ensuing self-scrutiny of standard editorial operating procedures and beliefs, that the editors of Infection and Immunity and mBio coined the term “retraction index” (21). This index represents the number of retractions, multiplied by 1,000 divided by the number of published articles with abstracts in the same time-span of 10 years. To put a mathematical spin on the retraction index, it may be represented as:

where R10 is the number of retracted articles, and PA10 the number of articles with abstracts published in 10 years. What the “freshly-burned-by-a-scandal” introspective editors also found was a correlation between a journal’s IF and its retraction index, which stated that the higher the IF of a journal, the higher the probability of a retraction. This, again, takes us back to the high visibility of journals with high IFs and a scrutinizing readership. So it seems this circle is not so vicious, as the higher the IF of the journal that unknowingly published fraudulent research, the greater the post-publication scrutiny, and the greater the chance of retraction and self-correction! OK! We are done here and you may, now, stop reading this article and feel safe that all is well in the world of scientific publishing!?

(Ir)reproducibility of published research

Out of all the reasons for retractions (9), irreproducibility of results inhabits its own troubling niche. Reproducibility or replicability of experiments is the core tenet of the scientific method. It is the reason why scientists obsessively write (and read) the Materials & Methods (M&M) sections of research articles. M&M need to be clear enough, and strike the right balance between length, detail, and brevity to allow repetition and validation of the study (22). Providing adequate citing is used, the verbatim transcription and reuse of portions of already published portions of M&M has its own shady grove out of the piercing view of the all-seeing glare of the plagiarism detecting software, and need not, necessarily, be considered plagiarism (23). A true mouthful, just to be able to justify re-usage of highly technical and formulaic portions of text which may lose consistency and validity when paraphrased (24). Still, sometimes, in spite of making the exact specifications and circumstances of one’s experiment public, other researchers fail to reproduce or replicate the published results. To test/confirm published results a group of researchers tried to replicate the results from 53 published “landmark” studies in biomedicine, and managed to confirm only 11% (25). Maybe I should put this differently. This group of researchers failed to confirm the results of 89% of 53 “landmark” studies published in biomedicine! This study, and others like it have led some researchers to doubt the veracity (of most) of the published research (26,27), and to organize into a “Reproducibility Initiative” (28), so they could, as it says on their web site, “identify and reward high quality reproducible research”. The idea is, also, backed by scientific journals (29) that wish to reinforce the trust in their work as well as educate the (scientific) public that just because something was published, does not make it final or true (30).

The impact of retractions – public (dis)trust?

Now that I have said all this, some questions remain – How important is any of this? Does it matter what happens to published articles and whether they are corrected or retracted? Who cares? Does it have real-life implications other than the embarrassment for the perpetrators? To answer the questions – yes; yes; the public/the funding agencies; and oh yes! (Now comes the part that I put the disclaimer at the beginning for).

The scientific endeavour, as I have tried to show, is far from perfect. Even when done with a clear head and of pure heart, the interpretation of data is often flawed and influenced by controllable as well as uncontrollable biases and confounding factors. The presentation of those data through the publication process adds another layer of possible bias. One need only to think of conflicting publications and interpretations of those publications about such topics as high blood pressure, effects of cholesterol in the diet on our health (eggs – is it OK to eat them now, or isn’t it?), GMOs, and climate change!? Or vaccination? A topic which touches upon most of the world (developed and developing) – with rising numbers of (very vocal) opponents to vaccination. Some of the groups that harboured distrust towards mainstream medicine and vaccination landed a victory when Andrew Wakefield (and 12 co-authors) published their “study” linking autism and MMR vaccination in The Lancet in 1998. That study, with the help of its author gained purchase and managed to push the vaccination scare to unprecedented levels (and the extent of unvaccinated children to highs not seen in the modern world since the introduction of vaccination). In the 12 years it had taken the journal to (fully) retract (31) this article (if was partially retracted in 2004), the study had been cited over 750 times, and (ab)used to further various, in hindsight, nefarious plots. Although the scientific record has “self-corrected”, untold hours and funds have been spent in useless endeavours to either confirm or debunk these claims.

Cases like this abound. To illustrate, please allow me to use one last example. Just this year, on January 30, 2014 the scientific journal Naturepublished 2 papers by Haruko Obokata et al. detailing reprogramming of somatic into stem cells by an acidic bath. The journal’s article metrics allow for some understanding of the impact these articles have attracted so far, before their inevitable retraction (at the time of writing this opinion piece, both papers are under investigation for fraud). Within approximately 50 days of publication, these two articles (taken together) have been tweeted about over 3300 times, appeared on more than 100 Facebook pages, picked up by 130 news outlets, cited a total of 30 times (which puts them above the 90th percentile of tracked articles of similar age across journals or in Nature), blogged about on at least 50 scientific blogs, and their web pages at the source through the nature.com journal platform have been viewed (HTML views and PDF downloads) more than 1,300.000 times total! I think these pieces of information allow us to qualify this as impact.

The solution?

Most of the cases of discovered fraud beg questions like – Why hasn’t this been discovered sooner? How did such drivel pass rigorous peer-review? Is science broken? Is the publication process broken? Whom do we trust?

Although, overall, the problem of retractions and fraudulent research represents a fraction of a fraction of all published research, subjectively it seems like the elephant in the room that may not be ignored. The challenge of maintaining (or regaining) trust of the public is real, and the authors, the editors, the publishers of scientific journals, and the interested public (including the funding agencies) with a vested interest should have a better understanding of the possible problems and possible solutions (32). To achieve that, we need data. To get the data we need research. To continue having the privilege to perform and publish research we need to be responsible and accountable.