Hepatitis during respiratory syncytial virus infection – a case report

Branka Kristić Kirin

[1]

Renata Zrinski Topić

[2]

Slavica Dodig

[*]

[2]

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is the most common cause of hospitalization for pneumonia and bronchiolitis in infants and small children (1). Epidemiological study concerning Zagreb County have shown that RSV-caused bronchiolitis has been registered in 52.7% of children who were hospitalized due to acute respiratory infection (2). The study confirmed biennial cycle of RSV outbreaks (3).

Mainly, bronchiolitis occurs in infants and small children up to two years of age. Bronchiolitis is seasonal illness (in the winter months), as RSV is widespread in the community. It is characterized by fever, nasal discharge, dry wheezy cough (the later because of small airway obstruction) (1). Infants and small children who are born prematurely (≤ 37 weeks) and children with cardiac disease are more susceptible to severe disease and have higher rates of hospitalization (4).

Recently, extrapulmonary manifestations (central nervous system, cardiovascular system, endocrine system and liver) of RSV-infection are described (5).

The aim of this paper was to present a 13-months-old male child with clinical signs and symptoms of airway infection and acute otitis media (AOM), and laboratory findings of liver disease during RSV-infection.

Material and methods

Case history

We present a case of a 13-month old boy, born at full term by Caesarean section, admitted to daily hospital department for the management of acute respiratory infection. The disease started ten days ago with productive cough. Febrility appeared four days before admission. On examination, the child was febrile (38.9 oC, axilary), had an impression of acute, moderately ill child. Mucosal secretion and nasal congestion were found by rhynoscopy. Pharyngeal mucosa was moderately hyperemic. Respiration rate was 40 breaths per minute. Bronchial breath sounds over the large airways and light wheezing were registered. Normal results on a pulse oximetry were registered (i.e. levels above 96% oxygenated haemoglobin). Signs and symptoms of pneumonia were not presented. Otoscopy has shown prominent and hyperemic right eardrum. Auscultatory, heart sounds were normal. Some angular lymph nodes were enlarged (diameter up to 5 mm), elastic and movable. Liver edge was palpable just below right costal margin. Finally, diagnoses of acute rhinopharingitis, acute rhinitis, obstructive bronchitis and right-side otitis media were confirmed. Serial determination of haematological and biochemical parameters were performed during hospitalization.

The patient was treated with salbutamol inhalations, decongestans and antipyretics. Salbutamol (0.15 mg/kg) was administered through nebulizer, according to the GINA guidelines (GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma) (7). Side effects of salbutamol therapy were not registered. In addition, respiratory physiotherapy and airway toilet were performed. After 11 days, the patient was discharged with normal clinical status for home care. Control physical examination and laboratory testing were performed on day 49 of the admission to daily hospital. The patient’s mother signed the informed consent form prior to admission to daily hospital. Diagnostic work-up was performed according to the standardized procedure, in line with ethical principles, Helsinki Declaration on Human Rights from 1975 and Seoul amendments from 2008.

Laboratory measurements

Determination of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate aminotranspherase (AST), alanine aminotranspherase (ALT), gamma glutamyltranspherase (GGT), lactate dehydrogenase (LD), bilirubin, C-reactive protein (CRP) and iron in serum were performed on Beckman Coulter AU 400 analyzer with original commercial reagents (Beckman Coulter, Munich, Germany) according to the recommended/harmonized methods (6). Erithrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was performed using the centrifugal laboratory analyzer Vesmatic 20 (DIESSE Diagnostics, S. Martino, Italija). Sysmex 1800i automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) was used for the determination of leukocyte count. Nasal wash kit has been used in the collection of nasal washing for RSV antigen isolation and detection (direct testing for RSV antigen).

Results

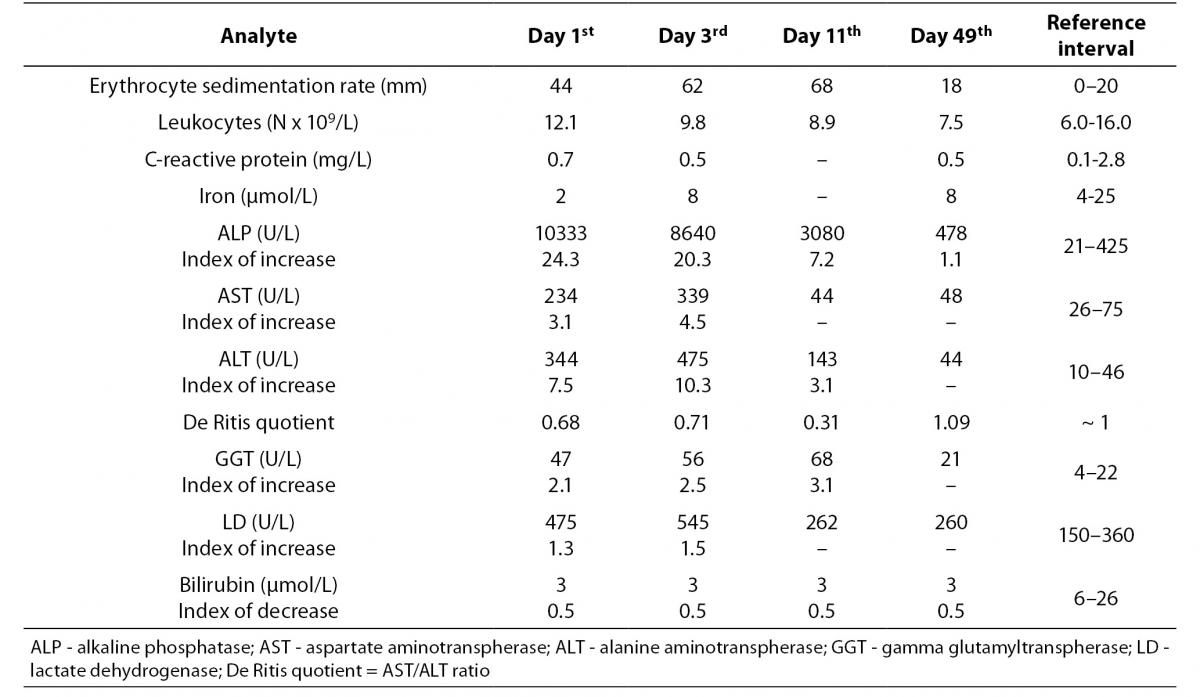

Dynamic changes of laboratory findings occurred during serial monitoring (Table 1). At admission, catalytic activity of ALP was markedly elevated (10333 U/L, i.e. 24.3-fold elevation in comparison with the upper reference value of 425 U/L). Thereafter, it decreased to 8640 U/L (at day 3; 84% of initial value), to 3080 U/L (at day 11; 30% of initial value), and finally to 478 U/L (at day 49; 5% of initial value). The highest increased in AST (339 U/L, 4.5-fold), ALT (475 U/L, 10.3-fold) and LD (545 U/L, 1.5-fold) were registered on the 3rd day, and the highest increase in GGT (68 U/L, 3.1-fold) occurred on the 11th day. Seven weeks after discharge AST, ALT, GGT and LD decreased into reference range, and ALP remained mildly increased (478 U/L, 1.1-fold increase). During acute illness De Ritis quotient remained < 1, and at control testing it increased at normal value, i.e. 1.09. All the time concentrations of bilirubin remain decreased (bellow lower reference value for age, i.e. < 6 μmol/L). During hospitalization, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ESR, remained increased. Leukocyte count, as well as the concentration of C-reactive protein, was into reference range. In addition, initial values of IgG (9.3 g/L) and IgA (0.47 g/L) were less than upper limit of the reference range for age, and IgM (1.48 g/L) was moderately increased (upper limit = 1.43 g/L). RSV was confirmed in nasal lavage fluid.

Table 1. Results of laboratory analyses during hospital treatment (day 1, 3 and 11) and after home treatment (day 49).

Discussion

Transient increase in catalytic activities of ALP, AST, ALT, GGT and LD revealed that the acute hepatitis may appear during the RSV-infection. According to our knowledge this is the first overview of markedly (24-fold) increased ALP during RSV-infection in children.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is medium-sized enveloped RNA paramyxovirus (8). In community, it spreads by direct contact, and replicates in nasopharingeal epithelium. In the next few days it spreads to respiratory epithelial cells of lower respiratory system. The transit of RSV to distant organs takes place haematogenously (9). The most studies on RSV-infections are related to pulmonary diseases. During RSV-infection, children up to two years of age have a high risk of concomitant acute AOM as a complication (10). In a systemic review, Eisenhut had point out to extrapulmonary manifestations of RSV-infections, especially in patients with severe clinical presentation (5). However, our patient was moderately ill, and extrapulmonary manifestations of viral infection were not expected.

The fact that RSV-infection has shown the biennial cycle (3) enables the prospective planning of measures to control infection. In 2009, the American

Association of Pediatrics (APP) has published a modified recommendations for the prevention of RSV-infection, using a humanized monoclonal antibody (directed against an epitope of RSV), Palivizumab (11). It is approved for the prevention of RSV disease in children up to 24 months, who are at high-risk because of prematurity and prematurity-associated lung diseases or congenital heart diseases.

Catalytic activites of enzymes and De Ritis quotient in our patient were typical for acute hepatitis (12). So, the present case report presents at least two issues for discussion: 1) concomitant infection with hapatotrophic viruses, eg. Epstein-Barr virus-infection, citomegalovirus (CMV)-infection, or influenca-virus, and 2) drug-side-effect, respectively. Hepatitis is common characteristics of viral infections, eg. Epstein-Barr virus-infection (13), CMV (14), or influenca-virus (15). So, it may be presumed that a similar pathomechanism of “collateral damage” of the hepatocytes could cause RSV-associated hepatitis. As the child has been febrile four days before admission, and was treated with antipyretics, transitory increase in catalytic activities of enzymes may be explained as side-effect of antipyretic medication. In children, acetaminophen (paracetamol) is often used for antipyresis, and it may cause transitory acute liver impairment (16). Eisenhut et al. have shown aminotranspherases to be increased in children with RSV-infection (17). Moreover, elevation of aminotranspherases (with peak value between two and four days after admission) due to hepatitis in these children was in correlation with the severity of respiratory disease (18), and increased ALT of nearly 3000 U/L was associated with severe hepatitis (5). The peak values of aminotranspherases and LD in the present study were registered at the 3rd day after admission to daily hospital. The half-life of ALP is referred to be between 5 and 25 days (12).

Benign transient hyperphosphatasemia (BTH) may appear during the season of viral infections (19-21). Our previous investigation revealed that both, bacterial and viral infections may be a direct cause of BTH (22). In that study, children with bacterial respiratory infection had higher ALP values than children with viral infections. However, in children with BTH there is no evidence of metabolic bone or liver disease. Increased catalytic activity of ALP is isolated and transient laboratory finding (23), and it returns into reference interval within four months (19). In patients with BTH, ALP may have 10-fold increase. In our previous study, values of ALP were in the range 528-5622 U/L (22), and Dori et al. have shown ALP values to be in the range 805-8619 U/L (24). Values of ALP over 10000 U/L are very rare in BTH – one case with 11900 U/L has been registered by Eyman et al. (25). Markedly increase of ALP at the admission in the child with hepatitis in the present paper has shown significant decrease at the 3rd day. It means that RSV-infection may cause short-time increase of ALP at the very beginning of hepatitis.

As liver biopsy is too aggressive and not ethically justified, determination of cytoxine and chemokine may be useful in assessment of the severity of RSV infection. Cepika A-M et al. have shown that low expression of chemokine receptor CX3 CR1 and perforin in peripheral blood had been linked to a more severe RSV-disease presentation in infants (26). In addition, cytokine polymorphisms have been associated with severity of rhinovirus or RSV infection as well as the frequency of AOM as a complication (27).

Oxidative stress contributes to the pathogenesis of lung inflammatory diseases (28). During infection-associated oxidative stress, human cells are exposed to high concentration of reactive oxygen species, ROS (29). In vitro and in vivo investigations have shown that RSV infection induces production of ROS (30). Moderately increased concentrations of serum bilirubin may improve outcome of disease. Since circulating bilirubin is considered to be an endogenous anti-oxidant (31), low serum bilirubin in our patient may reveal that oxidant - antioxidant balance has been impaired.

Signs and symptoms of respiratory manifestations and symptoms of AOM due to RSV infections disappear in about two weeks. However, the recovery phase of hepatitis during RSV-infection may last for weeks. Therefore catalytic activities of liver enzymes should be monitored until they return into reference range.

The main limitation of this case study is that ALP isoenzymes have not been identified. Therefore it is not clear whether markedly increased ALP is the consequence of the mechanism of transient hyperphosphatasemia or the mechanism of RSV-induced hepatitis. Additional serious limitation to this work is lack of proof that the liver function impairment was caused by RSV.

Laboratory results in patients with RSV infection needs to be interpreted in the light of both, respiratory and extrapulmonary manifestations of the infection, respectively.

Notes

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, Dherani M, Madhi SA, Singleton RJ, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1545-55.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1.

2. Mlinarić-Galinović G, Vilibić-Čavlek T, Ljubin-Sternak S, Draženović V, Galinović I, Tomić V et al. Eleven consecutive years of respiratory syncytial virus outbreaks in Croatia, Pediatr Int 2009;51:237-40.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02723.x.

3. Mlinarić-Galinović G, Welliver RC, Vilibić-Čavlek T, Ljubin-Sternak S, Draženović V, Galinović I, Tomić V. The biennial cycle of respiratory syncytial virus outbreaks in Croatia. Virology J 2008;5:18.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-5-18.

4. Deshpande SA, Northern V. The clinical and health economic burden of respiratory syncytial virus disease among children under 2 years of age in a defined geographical area. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:1065-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.88.12.1065.

5. Eisenhut M. Extrapulmonary manifestations of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection – a systematic review. Crit Care 2006;10:R107.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc4984.

6. Stavljenić Rukavina A, Čvorišćec D, eds. Harmonization of laboratory results in the field of general medical biochemistry: Croatian chember of medical biochemistry. Medicinska naklada, Zagreb 2004. (in Croatian)

7. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma in Children 5 years and Younger, Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2009. Available at:

www.ginasthma.org. Accessed May 18, 2011.

9. Thorburn K, Hart CA. Think outside the box: extrapulmonary manifestations of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection. Crit Care 2006;10:159.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc5012.

10. Tomochika K, Ichiyama T, Shimogori H, Sugahara K, Yamashita H, Furukawa S. Clinical characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus infection-associated acute otitis media. Pediatr Int 2009;51:484-7.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02768.x.

11. American Academy of Pediatrics. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, Kimberlin D, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Gove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:560–9.

12. Čvorišćec D, Čepelak I, eds. Štraus medical biochemistry: Medicinska naklada, Zagreb 2009. (in Croatian)

13. Pagidipati N, Obstein KL, Rucker-Schmidt R, Odze RD, Thompson CC. Acute hepatitis due to Eppstein-Barr virus infection in an immunocompetent patient. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:1182-5.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10620-009-0835-z.

14. Tezer H, Secmeer G, Kara A, Ceyhan M, Cengiz AB, Devrim I, et al. Cytomegalovirus hepatitis and ganciclovir treatment in immunocompetent children. Turk J Pediatr 2008;50:228-34.

15. Polakos NK, Cornejo JC, Murray DA, Wright KO, Treanor JJ, Crispe IN, et al. Kupffer cell-dependent hepatitis occurs during influenza infection. Am J Pathol 2006;168:1169–78.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2353/ajpath.2006.050875.

19. Behúlová D, Bzdúch V, Holešová D, Vasilenková A, Ponec J. Transient hyperphosphatasemia of infancy and early childhood: study of 194 cases. Clin Chem 2000;46:1868-69.

20. Dodig S, Demirović J, Jelčić Ž, Richter D, Čepelak I, Zrinski Topić R, Petrinović R. Transient hyperphosphatasemia in an infant with bronchiolitis and pneumonia. Eur J Med Res 2008;13:536-8.

21. Zrinski Topić R, Raos M, Demirović J, Živčić J, Čepelak I, Petrinović R, Dodig S. A new case of transient hyperphosphatasemia in a 21-month-old child with recurrent wheezing – case report. Biochem Med 2008;18:224-9.

22. Dodig S, Demirović J, Jelčić Ž, Richter D, Čepelak I, Raos M, et al. Alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes in children with respiratory disease. Biochem Med 2007;1:102-8.

23. Kutilek S, Bayer M. Transient hyperphosphatasemia - where we stand? Turk J Pediatr 1999;41:151-60.

25. Eymann A, Cacchiarelli N, Alonso G, Llera J. Benign transient hyperphosphatasemia of infancy. A common benign scenario, a big concern for a pediatrician. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2010;23:927-30.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/jpem.2010.148.

26. Cepika A-M, Gagro A, Baće A, Tješić-Drinković Do, Kelečić J, Voskresensky-Baričić T, et al. Expression of chemokine receptor CX3CR1 in infants with respiratory synsytial virus bronchiolitis. Pediatr Allery Immnol 2008;19:148-56.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00611.x.

30. Hosakote YM, Liu T, Castro SM, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Induces Oxidative Stress by Modulating Antioxidant Enzymes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;41:348–57.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2008-0330OC.

31. Wiedemann M, Kontush A, Finckh B, Hellwege HH, Kohlschütter A. Neonatal blood plasma is less susceptible to oxidation than adult plasma owing to its higher content of bilirubin and lower content of oxidizable Fatty acids. Pediatr Res 2003;53:843-49.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1203/01.PDR.0000057983.95219.0B.