Introduction

The Directive 2010/32/EU “Prevention from sharp injuries in the hospital and healthcare sector”, which was issued to protect healthcare workers (HCW) from the risk of occupational exposure and infection with bloodborne pathogens, came in effect on May 11 2013 (1); by this date Member States should have incorporated into national legislation and implemented its requirements, hopefully leading to a complete and coherent program for the prevention of needlesticks and sharps injuries (NSI) and of their consequences throughout Europe.

As laboratories represent a high-risk setting both in the preanalytical and analytical phase, we reviewed exposures and preventative measures in this setting in the light of the new legislation, starting from the long-lasting, nationwide experiences of the study groups on occupational risk of exposure and infection with bloodborne pathogens established in Italy and France since the end of the 1980s, following the first reports of cases of infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus among HCW.

At-risk procedures: a review of occupational cases of bloodborne exposure and infection in the health care and laboratory settings

Laboratory workers are exposed to a wide range of hazards during each stage of their work; collection, transport, processing, and analysis of patient specimens all represent critical opportunities for contamination or NSI in laboratory workers. However, some procedures carry an increased risk of occupational bloodborne pathogen transmission, namely those involving hollow-bore needle placement in the source patient’s vein or artery such as phlebotomy, in which, if a NSI occurs, a larger volume of undiluted blood can be transferred thereby increasing the likelihood of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (2) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (3).

In Italy, within the ongoing active surveillance carried out in the network of hospitals participating in the Italian Study Group for Occupational Risk of HIV Infection (Studio Italiano Rischio Occupazionale da HIV, SIROH) program, of all occupational cases of HIV and HCV seroconversion following percutaneous exposures identified since 1986 and 1992, respectively, almost half - two out of four for HIV and 16 out of 33 for HCV - were related to phlebotomy (4); two of the HCV cases occurred in laboratory workers. Moreover, one case of simultaneous occupational infection with HIV and HCV was documented in a housekeeper working in a medical biochemistry laboratory, who sustained a blood splash in the eyes despite the facial screen when disposing of open tubes containing residual blood (5).

In France, where a national surveillance of HIV and HCV occupational infections is performed by the Institut de Veille Sanitaire, 11 of 13 documented cases of HIV and 22 of 63 of HCV following a percutaneous exposure were related to phlebotomy; additionally, 4 possible HIV cases, and 4 HCV cases, occurred in laboratory workers during specimens processing and analyzing (6).

Worldwide, out of 106 reported cases of documented and 238 possible occupational HIV infection identified in the literature as of December 2002, 128 (37.2%) occurred in nurses, 42 (12.2%) in doctors, and 39 (11.3%) in phlebotomists, classified as ‘clinical’ laboratory workers in the United States (all other cases involving phlebotomists have been classified under nurses); non-clinical laboratory workers account for seven cases, mostly related to an exposure to concentrated virus. Of 77 documented cases for whom the exposure has been reported in detail, 35 (45%) were related to phlebotomy: six doctors, 18 nurses/phlebotomists, 3 student nurses, 8 unspecified (7).

Phlebotomy-related exposures and risk of injury for laboratory workers

Phlebotomy in Europe is most commonly performed by nurses, as shown by the results of the European survey on phlebotomy practices (8), but also by laboratory technicians, junior doctors and specialized phlebotomists.

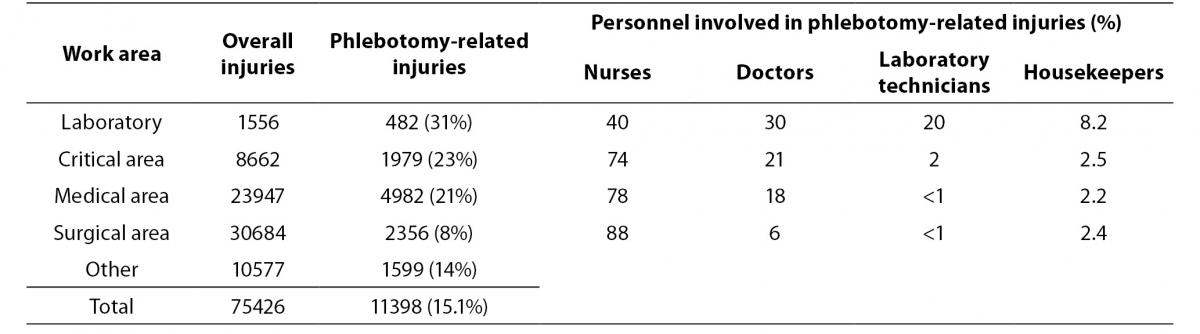

Whoever might be in charge of performing phlebotomy, the frequency of associated NSI is high: one in six of the 75,426 percutaneous exposures reported within the SIROH from January 1994 to June 2013 were related to blood drawing (venous and arterial sampling), with approximately one in five involving a bloodborne-infected source (Table 1). Phlebotomy-related NSI are more frequent in the laboratory setting than in other areas. These accidents involved mainly nurses in all areas except for the laboratory, where different categories perform phlebotomy and should consequently undergo specific training to prevent exposure. Moreover, a higher frequency of NSI with phlebotomy-related devices was observed in laboratory auxiliary personnel suggesting risks related to devices disposal.

Table 1. Needlesticks and sharps injuries related to phlebotomy. Studio Italiano Rischio Occupazionale da HIV (SIROH) nationwide surveillance program, January 1994-June 2013 (SIROH internal report, June 2013).

Of 24,009 mucocutaneous exposures reported within the SIROH in the same period, 4% (N = 960) took place in the laboratory: 65% occurred while transporting and manipulating biological samples, 6% while performing phlebotomy to the patient, 14% while cleaning and decontaminating the environment. This suggests a low compliance with personal protective equipment: indeed, in most cases, the worker was only wearing gloves and a coat; eyewear was missing in 85% of cases (and of the remaining 15%, more than half was represented by prescription glasses) and face protection to cover nose and mouth was present in 35% of cases (SIROH, internal report, June 2013).

In France, the incidence of accidental blood exposure per 100 full-time equivalent positions (FTE) in nurses followed a decreasing trend due to the introduction of preventive measures, from 32/100 FTE in 1990 to 7/100 FTE in 2000 (9); data from the RAISIN national surveillance on 810 hospitals found a further decrease, with nurses reporting 4.4 percutaneous exposures per 100 FTE in 2010. However, these data derive mainly from the public sector, while data from the private sector, where phlebotomy is frequently performed by laboratory technicians, are lacking. In a study carried out in 91 private laboratories in 2005 by the Study Group on the Risk of Exposure for Healthcare Workers (Groupe d’Etude sur le Risque d’Exposition des Soignants, GERES), phlebotomists working in private laboratories had a higher exposure rate during venous blood sampling (11 per 100 phlebotomists/year) than nurses working in hospitals (7 per 100 nurses/year). Observation of practices revealed that Standard Precautions were well known and observed except for wearing gloves (in only 5.5% of cases), while available, and that sharps containers were available in most laboratories (96%) and used in most cases consistently with good practices (though 12% of containers were out of arm’s reach, and 10% were overfilled); however, high-risk practices were observed after blood collection: blood transferring in 15% of cases, needle disassembly by hand in 10% of cases, and needle recapping in 1% of cases (10).

An integrated approach to prevention: the Directive 2010/32/EU

In the European Union (EU), legislation to improve the safety and health of workers has been in place since 1989 (11). In 2000 a specific directive on workers’ exposures to biological agents was issued, which included “design of work processes and engineering control(s)” among its protective measures (12). On May 10, 2010, the European Council adopted Directive 2010/32/EU on “Prevention from sharp injuries in the hospital and healthcare sector”, issued to specifically protect HCW from the risk of occupational NSI and subsequent infection with HIV and other bloodborne pathogens (1). The Directive came in effect on May 11 2013, by which date all Member States should have incorporated its requirements into their national legislation and implemented its intended preventive interventions as far as possible. This Directive is the result of the successful and fruitful dialogue between exposed workers and healthcare employers, represented by the European sectoral social partner organizations – the European Public Services Union (EPSU) and the European Hospital and Healthcare Employers’ Association (HOSPEEM) – in a unique experience illustrated also in a video realized by the European Commission (13). Experts from the SIROH provided data and expertise in support to the Social partners in the development of a framework agreement requiring an integrated approach to prevention: awareness-raising, education, training, elimination of unnecessary needles, safe procedures for using and disposing of sharps, banning of recapping, vaccination, use of personal protective equipment, provision of medical devices incorporating safety-engineered protection mechanisms, and appropriate surveillance, monitoring, response and follow-up of accidentally-exposed workers, are all necessary elements to create a safer working environment for HCW, the “bricks” building up a wall against occupational risks.

The brick wall of safety

1. Awareness-raising

Raising awareness among HCW about the risks possibly deriving from their everyday activity is the first step to ensure they understand the reason for a strict adherence with preventive behaviours, which include safe procedures for using and disposing of sharps, and banning of recapping.

Within the healthcare setting, the laboratory is one of the areas at highest risk for the biological hazards present in clinical and research laboratories: more than 5000 cases of laboratory-associated infections, acquired through different routes (ingestion, inoculation, inhalation, contamination of skin and mucous membranes), have been reported in the literature over the last 100 years with a mortality rate of approximately 4% (14).

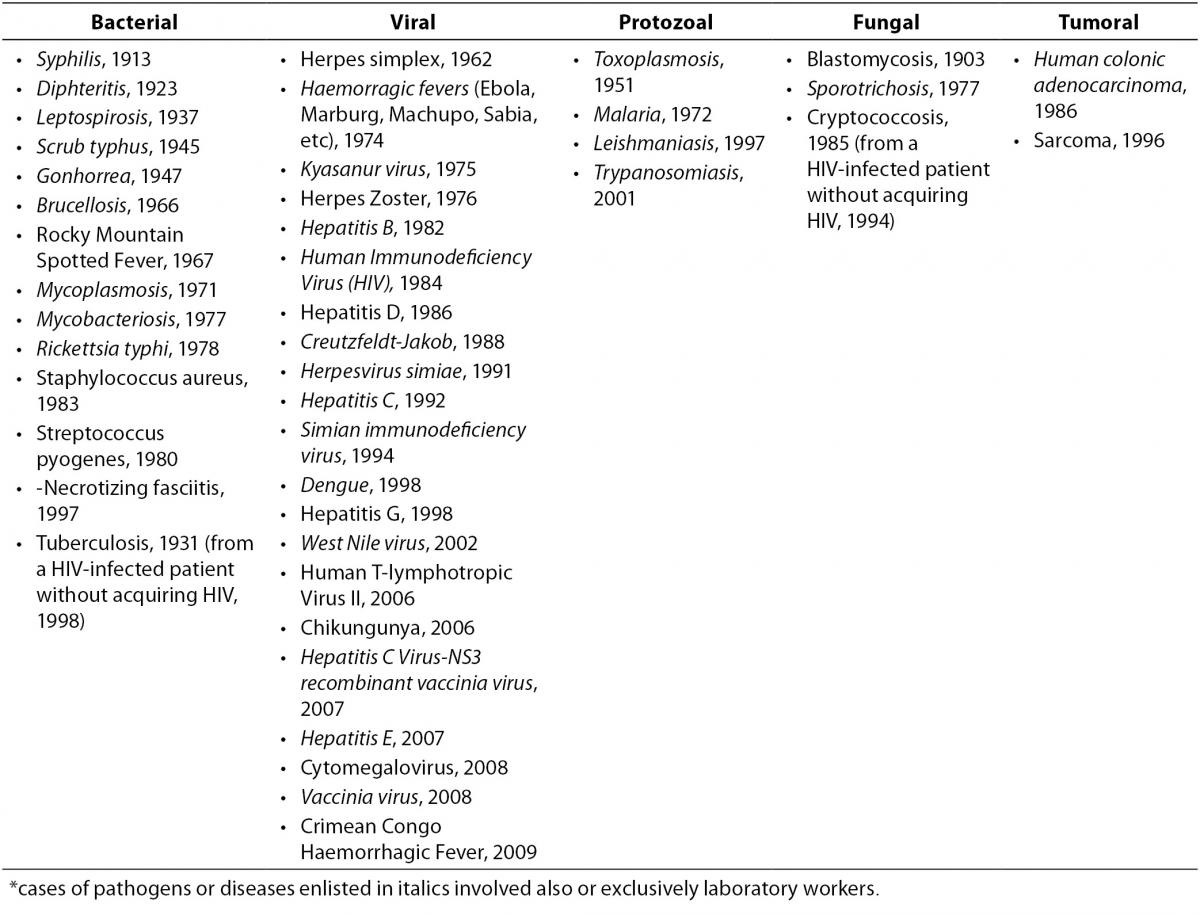

The first reports of occupational infection from serum hepatitis (later classified as most likely due to Hepatitis B Virus, HBV) emerged in the 1940s and involved blood bank workers, pathologists, and laboratory workers (15-17). These reports alerted investigators to the risk of occupational blood exposures, subsequently confirmed to be significant: laboratory workers, along with surgeons, were among the most exposed professionals, with hepatitis being the third most frequent agent(s) of 159 involved in laboratory-acquired infections (18). Of all the pathogens or diseases which determined an occupational illness following a NSI in a HCW, most involved also or exclusively the laboratory setting (Table 2) (19-22). However, it was the appearance of HIV which emphasized the urgent need for minimizing the risk of blood exposure during all phases of the laboratory process: HBV, HCV and HIV together account for the vast majority of cases of occupational infections in the healthcare and laboratory setting nowadays (19,23).

Table 2. Cases of occupational infections and diseases acquired through a needle or sharps injury in healthcare and laboratory settings, by year of first report in the literature* (19-22).

2. Safer use and disposal of needles

Considering the different phases of needle manipulation, of the 11,398 phlebotomy-related exposures reported in the SIROH, 6% occurred while recapping, 5% while disassembling the used device by hand, and 22% after use but before disposal: in summary, 33% of these exposures (more than 3,700 injuries) could have been prevented by adopting a correct behavior in the manipulation and disposal of used devices. As shown by the GERES study in private laboratories, these incorrect behaviours were observed among phlebotomists, probably accounting for at least a quote of their higher injury rate per 100 FTE in comparison to nurses. Used needles should be immediately disposed of, following the completion of the procedure: disposing of used devices in a sharps container all or most of the times was found to decrease the odds of sustaining a NSI of 82% (24). However, 24% of NSI in the laboratory reported in the SIROH occurred while disposing of the used device in the sharps container (18% of NSI in other areas), and 12% occurred with a device protruding from an overfilled container (3.3% of NSI in all other areas). These data as a whole might reflect problems in the management of sharps containers, supported by the observation of a 10% of overfilled containers in the GERES study (10), but the frequent injuries at disposal also reflect the use of winged-steel needles for phlebotomy, very common in Italy but not in Europe: these devices account for 43% of injuries at disposal in the laboratory setting, because of their long tubing coiling in the so-called “cobra effect” (25).

Including also NSI with devices disposed of into inappropriate containers (1% on average), almost 54% of overall phlebotomy-related exposures reported in the SIROH, and 70% of those reported in the laboratory setting, occurred after the procedure had been completed, when the needle device had to be eliminated. The Directive states “Where the results of the risk assessment reveal a risk of injuries with a sharp and/or infection, workers’ exposure must be eliminated by […] eliminating the unnecessary use of sharps by implementing changes in practice and on the basis of the results of the risk assessment, providing medical devices incorporating safety-engineered protection mechanisms” (1).

3. Elimination of unnecessary needles

Blood transfer from syringes into tubes represent an example of an unnecessary use of needles in the laboratory setting which could be eliminated: this practice was observed post-phlebotomy in 15% of cases in the GERES study (10), and was the mechanism of 4% of phlebotomy-related NSI in the SIROH.

Of course, the elimination of unnecessary blood tests could have a more significant impact in decreasing phlebotomies and the consequent need to analyze the collected samples, thereby reducing the chances for NSI and mucocutaneous exposures to occur. There are differences in the frequency of requested blood tests between different institutions, with one study demonstrating that teaching hospitals collect more samples (a wider follow-up of the patients or a greater number of requests by inexperienced doctors?), but also detecting geographic differences which can only be explained by a different organizational culture (26). Establishing a good relationship between the clinicians and the laboratorians would result in a more appropriate request for blood tests, increasing their diagnostic power, and avoiding unnecessary repetitions (27).

This relationship with the clinicians is one of the factors which should be considered in the standardization of the preanalytical process, which in turn could help in maintaining safer phlebotomy. Indeed, the preanalytical phase includes a set of processes that are difficult to define because they take place in different places and at different times. While quality control systems designed to ensure the quality of the analytical phase are highly developed and in use at most clinical laboratories, this is not the case for the preanalytical phase. Prescription from many different clinicians, as well as outsourcing of the sampling process, could be some of the causes In the analytical phase, processes take place within the laboratory and involve few people; consequently, the variables that need to be monitored are limited and well defined. The preanalytical phase, in contrast, involves many processes, most of them external to the laboratory; in addition, these processes are quite varied and involve many different people (patients, clinicians, phlebotomists, shippers, administrative personnel, and laboratory staff); as a result, these multiple variables, some difficult to define, must be monitored and managed by each laboratory.

Specifically regarding phlebotomy, the ISO 15189 standard (28) indicates that the specific instructions for extracting and handling samples should be documented and implemented by laboratory management and readily available to the sampling supervisors. The manual for primary sample collection must be part of the quality control documentation. This manual must contain instructions for, among others, procedures for collecting primary samples, and safe disposal of the materials used to obtain the samples (29); in these procedures, indications could be provided regarding the appropriate choice of the device.

4. Provision of safety-engineered devices

The choice of the device to be used for phlebotomy is of importance both for the safety of the patient- e.g. the use of catheters or small gauge needles may result in hemolytic specimens that might lead to an incorrect result - and that of the healthcare worker.

Provision of medical devices incorporating safety-engineered protection mechanisms (safety-engineered devices, SED) would significantly impact on all the exposures occurring after use: in a multicenter prospective survey performed in 32 French hospitals, use of SED during phlebotomy procedures was associated with a 74% lower risk of NSI, with the decrease in the NSI rate strongly correlating with increases in the frequency of SED use (9), in agreement with what has also been observed in the SIROH (30); a second survey in 66 French hospitals demonstrated also a correlation with the design of the device, in particular with the need for user activation (31). Indeed, in the latter study almost 25% of NSI occurred between the end of the procedure and device disposal, owing to user failure to activate the safety feature; additionally, one-third of NSI took place during activation of the safety feature, resulting from incorrect user activation of the safety mechanism rather than from failure of the device itself. This may be due to inadequate information and training of HCW. In a recent German study at the Heidelberg University Hospital, having a baseline injury rate of 69.0 per 1,000 FTE, training was performed in all departments by the Occupational Health Service and was obligatory for all healthcare personnel when the new safety devices were introduced: a significant decrease in injury rates was observed one year after introduction (52.4 per 1,000 FTE): overall NSI dropped by 22%, with a -46% for phlebotomy-related injuries adopting an user-activated device (32). At the University Hospital Birmingham National Health Service Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom, in 2003, when only standard training was provided, the number of NSI was 20/100,000 devices. However, the subsequent introduction of three safety needle devices, including phlebotomy needles, with concomitant training resulted in a significant reduction in the number of reported NSI to 6/100,000 devices in 2004 (33). In a Spanish general hospital, a program was implemented for the use of engineered devices to prevent percutaneous injury in the emergency department and half of the hospital wards during several at-risk procedures, including vacuum phlebotomy and blood-gas sampling; the program included a course on occupationally acquired bloodborne infections, and “hands-on” training session with the devices. A 93% reduction was obtained in the relative risk of percutaneous injuries in areas where safety devices were used (14 vs. 1 percutaneous injury), demonstrating that proper use of engineered devices is a highly effective measure to prevent NSI among HCW, however, education and training are the keys to achieving the greatest preventative effect (34).

5. Education and training

Education and specific training are of utmost importance in decreasing occupational risks of percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposure to blood and body fluids (35). Education played an important role in decreasing NSI rates in the past, when SED were not available, as it decreased recapping, unnecessary needle manipulation and improper disposal of used devices (36,37). More recently, when educational programmes were implemented alongside a SED, lower rates of sharps injuries were sustained for longer, but the benefit attributable to education alone could not be isolated from the impact of the introduction of the safer device (38). Nonetheless, any change, to obtain significant results, should be accompanied by an educational intervention, illustrating the rationale and consequences of the change. This intervention should then be repeated over time and accompanied by a monitoring of adherence to the change, to ensure that the objectives were achieved and maintained (39). Among laboratory personnel, periodic renewal of biosafety training may be important in reinforcing institutional safety expectations and providing an opportunity to review new safety measures, such as the adoption of new devices incorporating a protection mechanism, as well as reminding about “old” safety measures, such as wearing personal protective equipment appropriate for the activity to be carried out. This is even more important because the whole workforce, in healthcare and in laboratories, is ageing. The Fourth European Working Conditions Survey highlights specific problems encountered by ageing workers in the workplace. Particularly, the survey shows that workers aged 45–55 report higher exposure to risks during their working activity and that older workers receive less training and have more limited access to new technologies than younger workers. On the basis of these findings, access to training especially for older workers, need to be further ensured and encouraged (40).

This is crucial to increase adherence with infection control precautions - including a consistent use of personal protective equipment - of great importance in every healthcare activity but particularly in the laboratory setting. Indeed, the concern for the prevention of injuries and occupational infections in U.S. laboratories prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue specific guidelines for the diagnostic laboratories in human (and animal) medicine, in which quality laboratory science is reinforced by a common-sense approach to biosafety in day-to-day activities (41), supplementing the reference manual “Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories” (BMBL-5).

6. Vaccination against Hepatitis B

Among the many issues regarding all the activities carrying a risk, from sample collection to the use of technology and the exposure to physical and chemical agents, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines repeatedly address the need for hepatitis B vaccination of exposed workers, and for maintaining a record of vaccination, also required in the ISO 15189 (28).

A survey conducted in laboratories across Canada found that 15% of respondents reported incomplete hepatitis B vaccination (42). Before widespread HBV vaccination was in use, pathologists, blood bank personnel and laboratory technicians had the highest cumulative prevalence of all HBV serologic markers among all occupational categories in hospitals (≥ 25%) (43,44), confirming that laboratory staff should be encouraged to start or complete a standard HBV vaccination cycle early during education or at least at employment. According to the Directive requirements, vaccination must be offered free of charge to all workers and students, and workers must be informed of the benefits and drawbacks of both vaccination and non-vaccination. This latter aspect is particularly important, because incorrect or incomplete information may hinder acceptance or completion of vaccination (45).

7. Reporting and recording

Notwithstanding all preventive interventions, accidents still may occur. Clearly, a surveillance of occupational exposures should be activated in every healthcare setting to monitor injuries and contaminations and identify the need for corrective interventions: a “no blame culture”, as stated in the Directive, should be in place to encourage reporting.

Indeed, incidents, for the Swiss cheese theory, are always the final result of a series of “holes” - structural, administrative, technological and behavioural, which align, allowing for the injury to occur: the final responsibility should not lie on the exposed worker only. As reminded in the Directive, “Incident reporting procedure should focus on systemic factors rather than individual mistakes” (1).

According to the Directive, reporting mechanisms should include local, national and European-wide systems: in Italy and France, local merging into national systems are in place, in Spain there are regional systems, in the UK systems involve Trusts; there are several good systems which can be taken as examples or adopted, for those facilities wishing to implement a local reporting system to collect data to be used for preventive, administrative and educational purposes (46).

In the Directive, it is stated that monitoring (i.e. close observation of the evolving risks, changes in procedures, in behaviours, new technologies) is a responsibility of the health employer, as well as encouraging and facilitating HCW participation in educational courses, and providing personal protective equipment and safety devices as appropriate and whenever available; HCW, in turn, must attend these courses and comply with prevention requirements.

8. Response and follow-up: post-exposure management

Monitoring also indicates the need and duty of the employer to fully record every accident and provide a follow up of the injured worker after the exposure, for which event a response (policies and procedures for the post-exposure management, immediate steps for the care of the injured worker, availability of post-exposure prophylaxis) must be in place and well known by the HCW. In case of exposure, a risk assessment should be rapidly performed by another appropriate health professional to decide if a significant exposure has occurred and if there were factors increasing the risk of transmission of bloodborne viruses infection; to investigate the serostatus of the source, if known, or if the source is unknown or refuses testing, to assess the risk based on the characteristics of the exposure and any available information; to ascertain the HBV immunisation status of the exposed HCW and finally to decide immediate post-exposure actions like Hepatitis B and HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (47).

The risk assessment should first consider the likelihood of HIV, HBV and HCV transmission, but if the source is infected with other agents, these should be taken into account in the post-exposure evaluation and follow up.

Blood is the body fluid most frequently involved in occupational cases of infection, but other fluids containing the agent(s) (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid) could also represent a risk. Percutaneous exposures carry a higher risk than mucous contaminations; however, the conjunctiva is also a frequent portal of entry for pathogens.

The average risk of HIV infection following a NSI with an HIV-infected, untreated source is < 0.5% (48); a deep injury, with a hollow-bore, blood-filled needle may however carry a 10-fold higher risk, further enhanced according to the source viral load (2). Antiretroviral post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) may protect the HCW against HIV. PEP should be started as soon as possible, ideally within one hour from exposure, and the risks re-evaluated after the results of HIV testing of source patient, performed with informed consent, are available; expert consultation should be available within 48-72 hours in any case (49,50).

If the HCW is susceptible for HBV or the specific response to previous vaccination is unknown, and the exposure involves a HBsAg positive or unknown patient, a dose of HBV vaccine should be provided as soon as possible, within 1-7 days, and then the situation re-evaluated by an expert with the serostatus of the source and the exposed worker; specific immune globulins may be indicated, one dose as soon as possible repeated after one month, for unvaccinated and not immune or non-responder HCW (51). In the absence of any post-exposure intervention, the risk of acute hepatitis B following a NSI with an HBsAg positive patient is estimated to average 5%, and that of seroconversion could reach 30%; these probabilities are higher if the source is also HBeAg positive (52).

The average risk of HCV transmission after a NSI is < 1% (53); the same factors identified to increase the possibility of HIV transmission (depth of the injury, presence of visible blood on the device, source viral load) significantly heighten this rate (3). So far, neither primary nor secondary prophylaxis are available; however, in case of infection, early treatment (during the acute or early chronic phase) has been observed to clear the infection in > 90% of cases (54,55); therefore, early identification of cases is desirable, and the follow up should be performed accordingly (56).

In any case, regardless of related risks, the psychological impact of an occupational exposure can be significant; the emotional distress for the exposed worker and relatives should be addressed in the post-exposure management, and further consequences prevented with appropriate counseling and support (57).

Conclusions

The safety of patients being paramount, and always bearing in mind that the primary goal of healthcare and laboratory procedures is the optimal care and well-being of the patient, the HCW should nonetheless be second in line. Transitioning to safer working practices may represent a great effort at the beginning, but entail significant results in the end. In this effort, the management commitment to safety is crucial to ensure the necessary support to these changes, including resources for education and training, the provision of safer materials, and adequate monitoring; at the same time, the HCW must perceive, and believe in, the management commitment to safety. If the organization is determined to pursue the adherence of workers to safe work practices, its workers are more likely to meet the standards: this virtuous cycle leads to a strong institutional safety climate, entailing a significant decrease of risks for HCW.

Acknowledgements

The SIROH program is supported by the Italian Ministry of Health - Ricerca Corrente IRCCS, and RF-2009-1530527 “Health technology assessment of needlestick-prevention devices to enhance safety of health care workers”.