Introduction

Numerous studies have been designed and conducted in the attempt to reduce the medical error rate; yet this issue still attracts public attention. It has been demonstrated that performance and outcome measures improve the quality of patient care. In particular, quality indicators (QIs) are valuable tools for quantifying the quality of selected aspects of care by comparing them against defined criteria. QIs can thus support accountability, be of help in making decisions and setting priorities, thereby enabling a comparison to be made between providers and the effectiveness of interventions (1). The recently released version of the International Standard for medical laboratories accreditation (ISO 15189: 2012) highlights the need to “establish quality indicators to monitor and evaluate performance throughout critical aspects of pre-examination, examination and post-examination processes” (2). In addition, the Standard ISO 15189:2012 stresses the point that “the process of monitoring quality indicators shall be planned, which includes establishing the objectives, methodology, interpretation, limits, action plan and duration of measurement”. Moreover, it underlines the need to periodically review indicators to ensure their continued appropriateness (2).

The identification and use of effective QIs in all phases of the total testing process (TTP) is therefore an essential requirement for laboratory accreditation, and for a valuable risk management strategy. Different QIs have been used in clinical laboratories in recent years in order to comply with the requirements of accreditation standards but, due to the different methods used for the identification and management of QIs, the results obtained by different laboratories cannot be compared.

The aim of the present paper is to describe and propose a new road map for the harmonization of QIs in the pre-analytical phase.

Laboratory-associated errors

Since the term ‘laboratory-associated error’ was coined a century ago (3), its meaning has completely changed. Originally the term referred to defects in the analytical performance of the test itself, in the so-called analytic phase. The first report on errors in laboratory testing, the seminal paper by Belk and Sunderman that paved the way to the development of external quality assessment programs (EQA), focused solely on analytical errors, and identified a high error rate in the measurement of “simple” clinical chemistry analytes (4). The new millennium has hailed a formidable improvement in the analytical phase with a ten-fold reduction in error rates, thanks to an improved standardization of analytic techniques and reagents, advances in instrumentation and information technologies, as well as to the availability of better qualified and trained staff. This achievement is also due to the development and introduction of reliable QIs and quality specifications for the effective management of analytical procedures (3). Internal quality control rules, as well as objective analytical quality specifications, and the availability of Proficiency Testing (PT)/EQA programs have enabled clinical laboratories to measure, monitor and improve their analytic performance over time.

Recently reported evidence indicates that most errors fall outside the analytical phase: the extra-analytical steps have been found to be more vulnerable to the risk of error (5-7). This calls for an evaluation of all the steps in TTP, whether or not they fall under the direct control of laboratory personnel, the ultimate goal being to improve, first and foremost, quality and safety for patients. However, the current lack of attention to extra-laboratory factors, and related QIs, is in stark contrast to the body of evidence pointing to the multitude of errors that continue to occur, particularly in the pre-analytical phase. Achieving consensus on a comprehensive definition of errors in laboratory testing (8) was a milestone in reducing errors and improving upon patient safety, and in promoting the use of QIs.

According to the Standard, the pre-analytical phase should be defined as “steps starting in chronological order, from the clinician’s request and including the examination requisition, preparation of the patient, collection of the primary sample, and transportation to and within the laboratory, and ending when the analytical examination procedure begins” (2). The same document defines the analytical phase as a “set of operations having the object of determining the value or characteristics of a property” and the post-analytical phase as “processes following the examination including review of results, retention and storage of clinical material, sample (and waste) disposal, and formatting, releasing, reporting and retention of examination results” (2).

The pre-analytical phase

In the definition of the pre-analytical phase made by the ISO 15189:2012, it is clearly recognized that there is a need to evaluate, monitor and improve all the procedures and processes in the initial phase of the TTP - the so-called “pre-pre-analytical phase”-, including test requesting, patient and sample identification, blood collection and sample handling and transportation. These procedures, which usually are neither performed in the clinical laboratory nor entirely fall under the control of laboratory personnel, are evaluated and monitored unsatisfactorily, often because the process owner is unidentified and the responsibility lies outside the boundary between the laboratories and clinical departments (3).

There is therefore a need for a patient-centered approach that encompasses not only the traditional on the procedures for sample acceptance/rejection and specimen preparation, but also all the activities necessary to make a sample suitable for analysis, such as centrifuging, aliquotting, pipetting, dilution and sorting (9). However, other fundamental procedures and processes (i.e. test requesting, patient and sample identification, sample handling and transportation to the laboratory), are error-prone, thus potentially putting patient safety at risk (10). Moreover, the increasing trend towards consolidation of laboratory facilities has created a need to transport numerous of specimens from peripheral collection sites to the core laboratories (11), thus incurring a dramatic increase in the risk of errors in this step.

Consequently, although traditional QIs address identification and sample problems, further aspects affecting quality and safety must be considered. In particular, the appropriateness of the test requesting and the completeness of the request forms are now recognized as key components in the provision of valid laboratory services, correct patient identification and sample collection being of fundamental importance in assuring total quality (12). Moreover, there is still an urgent need for appropriate sample transportation conditions and adequate QIs.

“Traditional” quality indicators for the pre-analytical phase

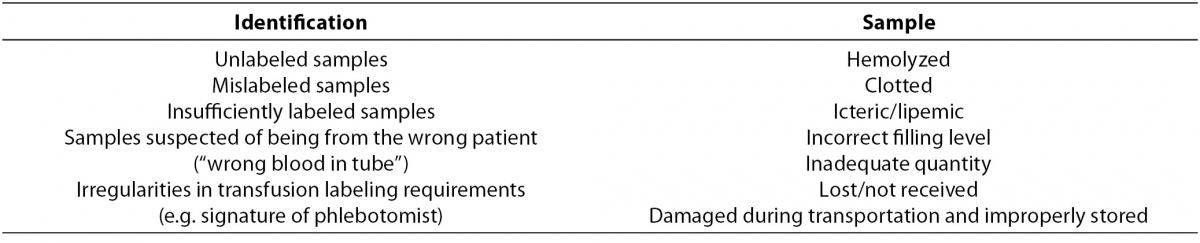

According to current literature, pre-analytical errors should be grouped in two categories, according to identification and sample problems, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Pre-analytical errors grouped in relation to identification and sample problems.

Data obtained following the development and use of QIs for the two main pre-analytical error categories several national and international programs are available in the literature (13,14).

For laboratory specimen misidentification, a rate of 1 in 1,000 opportunities has been reported, the most common categories of misidentification events being mislabeled (1%), mismatched (6.3%), and unlabeled specimens (4.6%), respectively (15). In general, misidentification occurs in 1 in 2,000 of specimens in transfusion medicine, while it occurs at a much higher rate (approximately 1 in 100) in clinical laboratory specimens. In fact, in transfusion medicine, technological improvements, improved education and training, and changes in policy and procedures have led to a significant reduction in, but not the elimination of, misidentification errors (16). In clinical laboratories, however, problems persist and greater efforts should be made to heighten laboratory professionals’ awareness of the pressing need to reduce this type of error. In fact, sample misidentification can have significant consequences for patients as it may result in unnecessary diagnostic procedures, delays in diagnosis or treatment, and physical harm (17).

The second category of traditional pre-analytical errors include sample problems. Hemolysis and samples in inadequate quantity are the primary cause of errors, the error rates for inpatients being significantly higher than those for out-patients (18). These observations are confirmed in a study reporting an error rate of 74.6% for inpatients and 25.4% for outpatients (19). In the last few decades, data have been accumulated to identify the rates of sample errors (6-7,20-21), to record the differences between rates for inpatients and those for outpatients, and to establish whether error rates are related to inadequate collection techniques and non-compliance with existing operational procedure guidelines (22). Differences in complying with operational procedures and problems related to inpatients’ disease severity (e.g. need for numerous needle sticks, presence of severe burns, fragile skin and veins) may explain why the sample error rate is lower in outpatients with care operators who are under direct laboratory control (20). Laboratory staff has appropriate training and education on practice guidelines for blood collection and sample handling, thus maximizing the safety of these procedures.

The use of pre-analytical workstations and tools such as serum indices in the laboratory has proven effective in decreasing most errors due to specimen preparation, centrifugation, aliquoting, pipetting and sorting (3,5,21), while no significant decrease in pre-pre-analytical mistakes (e.g. patient identification, unsuitable samples due to wrong collection procedures) has been achieved.

Now that intra-laboratory procedures have been made safer, greater attention should be paid to extra-laboratory procedures, harmonization of test request practices, guidelines for blood collection and sample transportation, the training and education of health care operators, and the use of serum indices to reduce pre-analytical errors (23).

Harmonization of pre-analytical quality indicators

The initial steps of TTP are not undertaken in the clinical laboratory; nor are they performed entirely under the control of laboratory personnel, and they are more error-prone than other steps (24,25). Recently reported data on errors in the pre-pre-analytical phase underline that failures to order appropriate diagnostic tests, including laboratory tests, accounted for 55% of observed breakdowns in missed and delayed diagnosis in the ambulatory setting (26-28), and 58% of errors in the Emergency department (29). In fact, most pre-pre-analytic laboratory errors involve some breakdown in the process, and both the laboratory and clinicians bear mutual responsibility for these errors and for developing safeguards that will prevent them. In particular, there is an emerging need to manage test demand to avoid unnecessary expenditure, reduce undue risk for patients and improve upon the use of laboratory services (30,31). The consensus achieved on the importance of advice for maximizing the appropriateness of test requesting led to the inclusion of a specific requirement (clause 5.4.2) in the ISO 15189 International Standard (2).

The steps undertaken to maximize appropriateness in test requesting must always be evaluated using indicators and long-term monitoring, which the laboratory should achieve by ensuring close interaction with the requesting physicians and obtaining recognition from the appropriate stakeholders. Another key issue related to test requesting, is the completeness of the request forms, a pre-requisite for the ultimate quality of laboratory results, as specified by the ISO 15189 International Standard (clause 5.4.3) (2).

QIs should be used to measure and monitor all the critical activities in the pre-pre- (outside the laboratory) and pre-analytical (within the laboratory) phases. In particular, they should be considered useful tools for identifying, documenting and monitoring the following:

- quality of request forms, whatever their format (e.g. electronic or paper) and the manner in which requests are communicated to the laboratory;

- patient identification at the point of care, which is still an issue of fundamental importance as it is related to a high risk of errors with an impact on patient care although the specimen identification errors involving secondary tubes should be reduced by introducing pre-analytical workstations;

- quality of biological specimens, particularly during and after transportation from collecting sites to the laboratory.

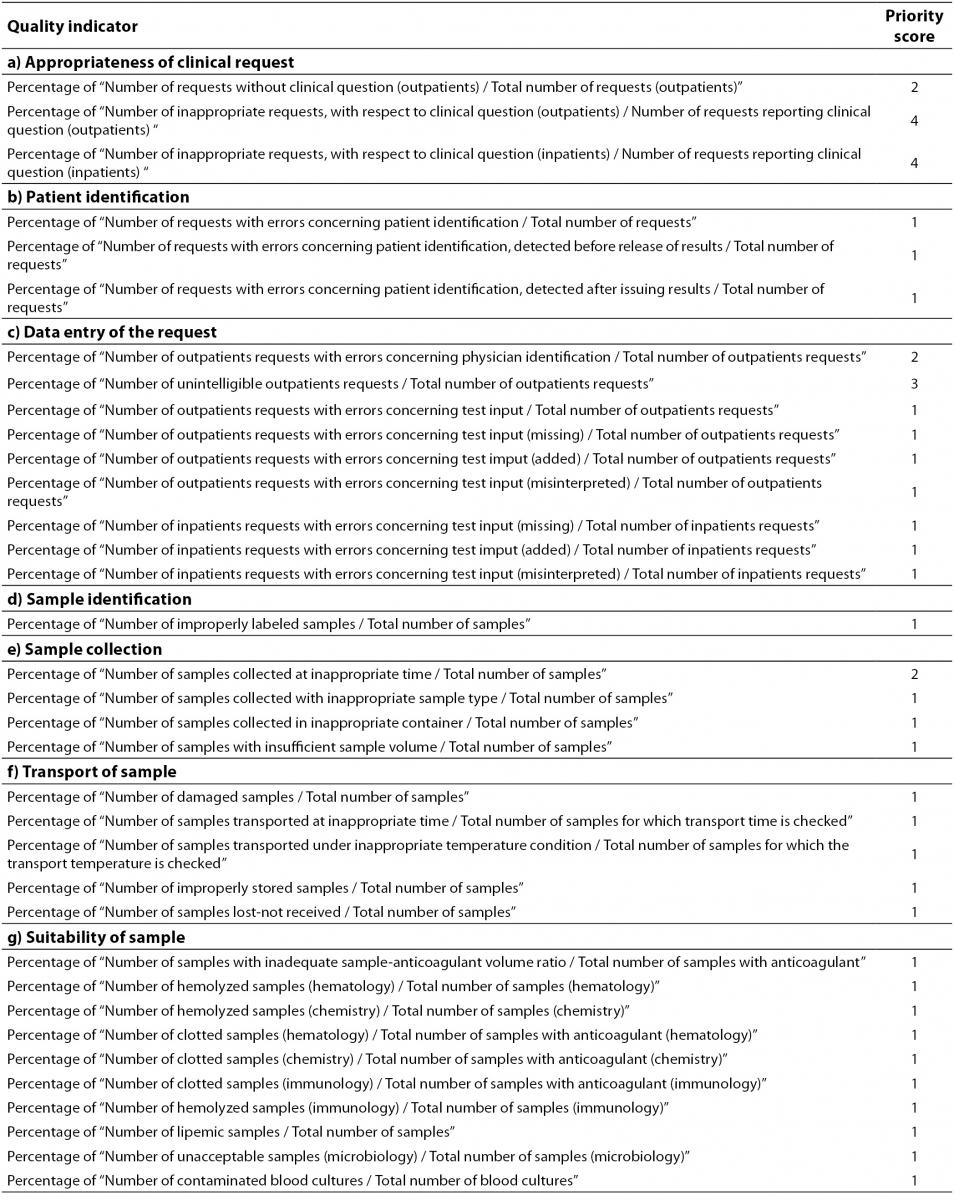

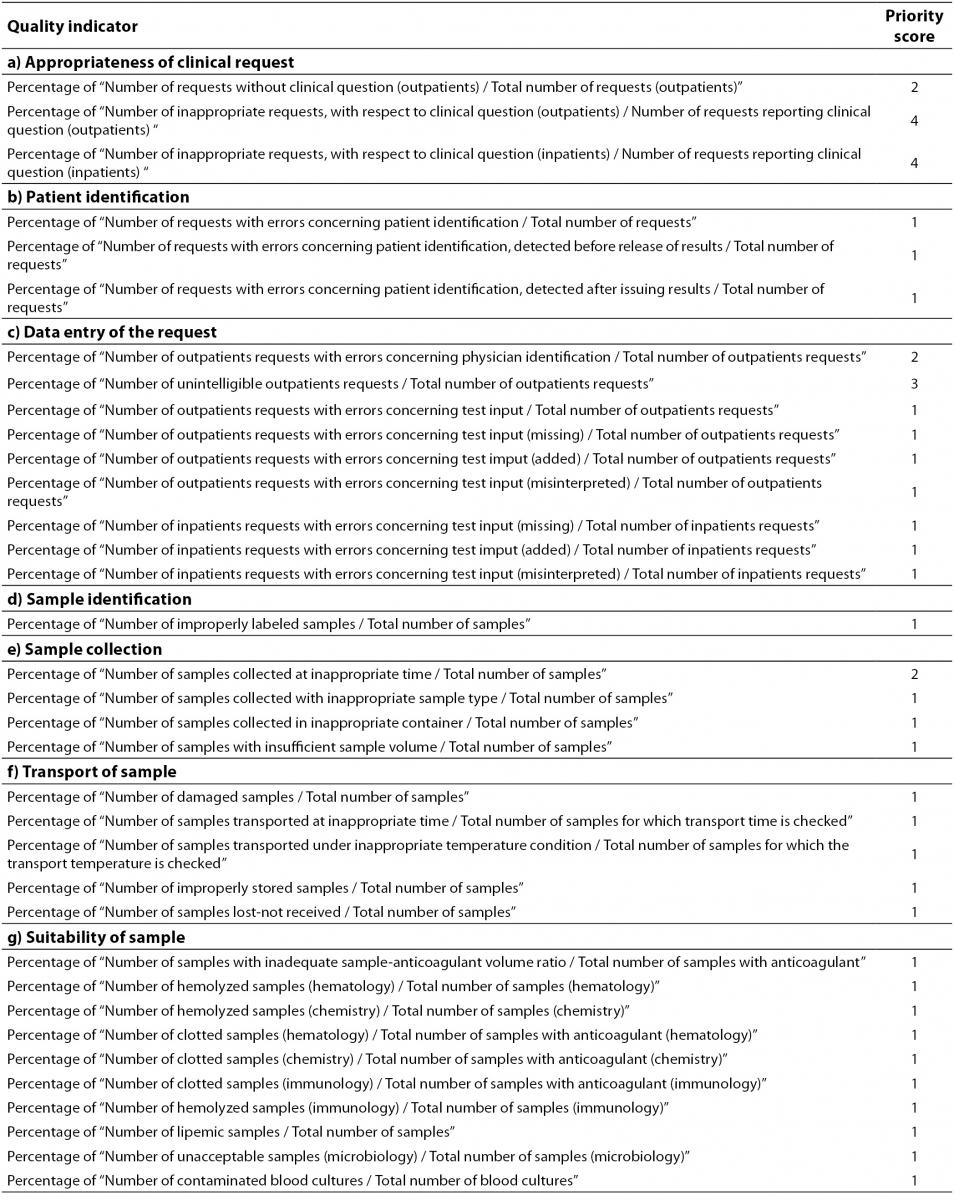

Table 2 shows the Model of Quality Indicators (MQI) proposed by the IFCC Working Group “Laboratory Errors and Patient Safety” (IFCC WG-LEPS) for the pre-analytical phase. The MQI aims to be the “backbone” of the monitoring and the key to improving upon laboratory performances. However, the effective adoption of QIs calls for a sound awareness in laboratory personnel of the importance of QIs as a quality assurance tool for improving the quality of laboratory service. The awareness and active involvement of the personnel is of crucial importance in overcoming problems related to data collection. Although, the implementation and monitoring using QIs incurs extra work and may, at first, be time-consuming, these apparent disadvantages are more than compensated by the reduced risk or errors, waste and operational repetition. Moreover, the method and time for data collection for each of the indicators shown in Table 2, should be firmly defined in order to clarify the events to check, and to harmonize the results obtained by different laboratories.

Table 2. Quality Indicators of the pre-analytical phase (order of priority: 1 = Mandatory; 2 = Important; 3 = Suggested; 4 = Valuable).

The priority score to be assigned to each QI is also of fundamental importance. The reason for identifying a priority scale for proposed QIs is to facilitate their gradual introduction into routine practice, by starting with a “mandatory” (score 1) and ending with a “valuable” (score 4) QIs score. “Mandatory” QIs ensure that the most critical activities (i.e. those incurring errors and risk of errors with potential negative clinical outcomes) are kept under control. In addition, “mandatory” QIs concern error-prone activities and/or procedures (i.e. acceptance/rejection of hemolysed samples) that should easily managed by most clinical laboratories. QIs identified as “important” should be implemented in the laboratory when all “mandatory” QIs are just in use and, likewise, for other QIs considered “suggested” (“advisable”) and “valuable”. Although important, the “valuable” QIs (priority scale 4), call for somewhat difficult data collection, and for laboratory staff acutely aware of the need for, and the importance of, QIs. The laboratories using QIs identified as “valuable” (in addition to “mandatory” and “Important” QIs) will raise their standard of quality management and TTP governance.

All QIs should be used in laboratories to provide evidence of compliance with essential requirements of the ISO 15189 International Standard for assuring quality and accreditation of laboratory services, particularly as they are a tool for assuring risk management and promoting patient safety; however, the priority score should also help laboratories when difficulties encountered in practice dictate that a choice must be made. Therefore, while the entire set of QIs is essential both for clearly understanding their usefulness and for complying with the requirements of the ISO 15189 International Standard, an individual laboratory should carefully select the most appropriate indicators to implement from the start, and over time. As quality assurance is a never-ending journey, the implementation and monitoring of QIs should be considered an essential component in a continuous quality improvement program. Therefore, progressive use should be made of QIs and monitoring should be encouraged so as to promote a valuable quality system program, based on the familiarization with the rationale of QIs and the appropriate method for data collection.

In the journey towards quality and patient safety, QIs should be viewed as a formidable tool for:

- highlighting critical processes/activities;

- analyzing and solving the root causes of non conformity;

- reducing laboratory errors and the risk of errors;

- improving laboratory performances.

The priority score (Table 2) described in the present paper can be considered a preliminary step in achieving harmonized guidelines following further consideration and discussion on the basis of different experiences made worldwide, by different laboratories.

A road map towards harmonization

Since a variety of QIs and terminologies are currently used, the road map for harmonization should be based on sound criteria. In particular, QIs should be:

- patient-centered to promote total quality and patient safety;

- consistent with the definition of “laboratory error” (specified in the ISO/TS 22367: 2008) and conducive to addressing all stages of the TTP, from initial pre-pre-analytical steps (test request and patient/sample identification) to post-post-analytical steps (acknowledgment of data communication, appropriate result interpretation and utilization);

- consistent with the requirements of the International Standard for medical laboratories accreditation (ISO 15189: 2012);

- suitable for promoting corrective/preventive actions.

Essential pre-requisites of objective and measurable QIs appear to be: 1) importance and applicability to a wide range of clinical laboratories worldwide; 2) scientific soundness with a focus on areas crucial to quality in laboratory medicine; 3) feasibility and the definition of evidence-based thresholds for acceptable performance; and 4) timeliness and possible utilization as a measure of laboratory improvement (10,11,32-35). Although the identification of valuable QIs is an essential step, other issues should be taken into consideration to assure a harmonized approach to the appropriate utilization of QIs in the pre-analytical phase. First and foremost, the standardization of the system for data collection and reporting plays a key role in assuring the comparability of data collected by different laboratories. This aspect prompted the IFCC WG-LEPS to split, in the MQI proposed, some QIs into different groups in order to facilitate the understanding and collection of data (34). Second, most QIs cannot be managed without the collaboration and active cooperation of different care operators both inside and outside the laboratory. For example, the appropriateness of test requesting as well as the quality of collected samples can be improved upon only through the active involvement of requesting physicians, phlebotomists and nurses. The development and issue, at an international and national level, of practice guidelines for appropriate test requesting and blood collection should facilitate compliance and quality improvement. Third, another fundamental issue is the automated collection of data on QIs, which obviates time-consuming procedures. The harmonization of QIs will be achieved by, above all, gaining consensus among experts in the field regarding current proposals, tools and steps required for a preliminary agreement, and then by defining actions to be taken for making the road map.

QIs management will be validated only by means of international consensus on criteria and methods for management itself. The accreditation providers play a key role in assuring the correct interpretation and application of the ISO 15189 requirements for QIs. The definition and the correct use of QIs, compliance with international recommendations, participation in appropriate EQA/PT programs and, above all, the translation from measures to errors reduction must be analyzed and evaluated during the survey visits in a way that allows staff efforts to be rewarded, and the correct use of QIs to be encouraged. Awareness of the IFCC WG-LEPS project, the comparison between external databases, and between the performance of laboratories and peer organizations, will lead to the realistic definition of laboratory goals, with a consequent improvement in performance and the realization and maintenance of excellence.

Currently, on preparing the Consensus Conference on “Harmonization of quality indicators in laboratory medicine: why, how and when?” (29), agreement has been achieved on the: a) value of QIs as an essential tool for accreditation and quality improvement in laboratory medicine, as well as their role in benchmarking and external quality assurance programs; b) need for QIs to comply with the above-described fundamental criteria; c) value of the IFCC MQI as a starting point for discussing and finalizing a consensual proposal on QIs.

In this context the future goals of the WG-LEPS concerning QIs could focus on promotion and divulgation of a set of consensually approved QIs, as well as on the collection of data from international laboratories in order to define the state of the art of laboratory errors, share the more appropriate corrective actions to be implemented and monitor the improvement achieved.

Conclusion

Indicators for laboratory performances in the TTP allow the quality of services to be measured and improved. According to the current definition of “error in laboratory medicine” all steps in the pre-analytical phase, including appropriateness in test requesting and request forms, patient and sample identification and quality of specimen transportation, must be evaluated and monitored. Of course, the road map for harmonization of QIs will comprise several steps and the identification of valuable QIs is a prerequisite in drawing it up, but the standardization of the system for data collection and reporting plays a key role in assuring the comparability of data collected by different laboratories. Moreover, few QIs can be managed without the collaboration and active cooperation of different care operators both inside and outside the laboratory. Therefore, although the harmonization process is in progress, further efforts must be made to raise the awareness of all stakeholders and to highlight the importance of QIs for improving the quality of laboratory services and patient safety. In particular, a simplification of the current MQI with the identification of “mandatory” QIs appears to be the key to allowing all laboratories to first select the most appropriate indicators and to gradually add further valuable QIs.