Introduction

Blood gas analysis is of vital importance for patients in critical or intensive care units. Sample collection, number of individuals who contribute in total testing process, instability of whole blood sample and other numerous factors result in multiple risks for reporting of unreliable results (1,2,3). International guidelines and standards for blood gas testing are available (4,5). Implementing standardized procedures according to widely accepted standards is essential for the continuous quality improvement and proper management of the total testing process of the blood gas testing (6).

Blood gas testing is routinely performed in general and specialized hospitals, clinical hospitals and university hospital centres in Croatia. The practices and policies in use in different institutions vary and there is no national standard or recommendation related to blood gas testing. To enable nation-wide harmonization across laboratory medicine, one of the major strategic goals of the Croatian society of medical biochemistry and laboratory medicine (CSMBLM) is to provide evidence-based recommendations for various segments of laboratory practice (7).

In order to harmonize blood gas testing and related measurements, CSMBLM has recently established a Working Group for acid-base balance within the Committee for the scientific and professional development. The aims of this working group are to assess the current practices and policies among laboratories in Croatia and to provide recommendations for the best laboratory policies and procedures related to blood gas testing.

The aim of this survey study was therefore to assess the current practices and policies in use related to the various steps in the blood gas testing process, across hospital laboratories in Croatia. We were particularly interested in sample type mostly used for blood gas analysis, steps taken during the sampling procedure, processing methods and presence of POCT (point of care testing) analyzers in institutions.

Materials and methods

Survey was performed in three consecutive rounds. In first round survey participants were defined. In second round participants responded to prepared questions related to policies and practices in blood gas analysis. Third round was conducted to clarify indeterminate answers. Survey was held from April to September of 2013.

First round

First round of this Croatian national survey on blood gas testing was performed from April to May 2013. An e-mail request was sent by Working Group for acid-base balance of the Committee for the scientific professional development of the Croatian society of medical biochemistry and laboratory medicine to 104 Croatian laboratories with the aim to identify laboratories which perform blood gas analysis and exclude all those that do not perform acid-base balance analysis at all and those institutions in which POCT blood gas analyzers are not under supervision of the central laboratory. Survey included laboratories within general and specialized hospitals, clinical hospitals and university hospital centres. According to Croatian law on healthcare system, clinical hospital is defined as general hospital with at least two clinics from the field of internal medicine, surgery, paediatrics or gynaecology and obstetrics and two additional departments from the other specialities or diagnostics. Clinic is defined as healthcare institution where specialist healthcare is performed together with university education program and scientific work.

Second round

After identifying institutions in which blood gas analysis is performed (in central laboratory or POCT supervised by central laboratory) (N = 47), those laboratories were invited by an e-mail invitation to participate in the on-line survey from May to September 2013. The on-line survey was performed using the SurveyMonkey tool (Palo Alto, CA, USA). Questionnaire was composed of five parts:

1. general questions about laboratory

2. sample type

3. sampling procedure

4. sample processing

5. POCT blood gas analyzers outside central laboratory

Heads of the laboratory in the general and specialized hospitals have been answering the survey questions. In clinical hospitals and university hospital centres, specialist in laboratory medicine responsible for blood gas diagnostics has responded to survey questions.

General questions about laboratory

In general questions section participants were asked to give their contact information which would be used only in the case of clarification of indeterminate and unclear answers as questionnaire was considered anonymous. Besides contact information, participants were also asked some questions about accreditation status of the laboratory and about their blood gas analyzers in use in central laboratory and POCT instruments, located outside of the central laboratory. Those laboratories which confirmed existence of the blood gas analyzers outside the central laboratory were asked to quote how many POCT analyzers are installed outside the central laboratory, on which wards, and which models of analyzers they use.

Sample type

Question related to sample type processed on blood gas analyzer was composed of the statements. They were addressed to arterial blood as preferred sample type and extent in which is capillary sample used for blood gas analysis in children and adult population. Participants had to declare whose responsibility in laboratory is blood gas sampling and processing.

Respondents agreement with the statements provided in this section was rated using the 5-point Likert scale (1 - never, 2 - rare, 3 - often, 4 - always, 5 - not applicable). Point 5 - not applicable relates either to the institutions which have blood gas analyzers exclusively on the ward, or to some specific reasons due to which respondents could not provide appropriate answer to the study question (e. g. due to some specificities in the population of patients).

Sampling procedure

Next section was related to blood gas sampling procedure and it was composed of statements on steps in procedure of blood gas sampling. These steps covered: specimen labelling, presence of the order form and/or electronic request and person responsible for arterial blood sampling. Special attention was given to procedure of anticoagulation of arterial blood specimen and steps which are performed by the laboratory personnel upon delivery of the sample to the laboratory. Statements which describe procedures related to capillary blood gas sampling included anticoagulation procedure, arterialisation of the puncture site, possible interstitial fluid and air contamination risks and avoiding of clot formation. Final set of statements in section Sampling procedure was addressed to time recording of each step of blood gas sample testing from sampling through delivery to sample processing on analyzer.

Respondents agreement with the statements provided in this section was rated using the 6-point Likert scale (1 - never, 2 - rare, 3 - often, 4 - always, 5 - I do not know, 6 - not applicable). Answer 5 - I do not know was related to statements on arterial blood sampling on hospital wards.

Sample processing

Next question was about blood gas sample analysis. Question was composed of 11 statements which comprised reporting of results for electrolytes and metabolites from blood gas analyzer, performance of internal and external quality control and recording of nonconformities and personnel education.

Possible answers were 1 - yes, 2 - no and 3 - not applicable. Category 3 - not applicable was addressed to those institutions which have only POCT blood gas analyzers and do not have analyzer in central laboratory.

POCT blood gas analyzers outside central laboratory

Last question was related exclusively to the POCT blood gas analyzers. Following statements and questions were included in last question: education and certification of ward personnel for sampling and processing of blood gas samples, quality control performance, presence of standard operating instructions and performance of maintenance.

Possible answers were 1 - yes, 2 - no and 3 - not applicable. Answer 3 - not applicable was addressed to the institutions which have blood gas analyzer situated in central laboratory.

Third round

After data were collected and analysed, some additional questions were circulated by e-mail to the 47 study participants, during September 2013 to clarify indeterminate and unclear answers. Additional questions were as follows:

1. Please, quote average number of samples analyzed on blood gas analyzer per day. Also, quote how many are there capillary and arterial samples per day. If you perform blood gas analysis occasionally, please, quote an average number of blood gas samples per week.

2. Please, describe procedure of labeling of capillary blood gas sample (e. g. operator labels directly capillary with the label containing patient data, or operator does not label directly capillary, but labels the written test order which accompanies blood gas capillary sample).

3. Is there a hospital information system in your institution? If there is, do you receive orders for blood gas analysis via hospital information system?

4. Please, describe the procedure of recording of sampling time and time of delivery of the blood gas sample to the central laboratory and time of blood gas sample processing on the analyzer.

5. Please, describe procedure of quality control on your blood gas analyzer. Do you use commercial quality control materials (please, quote which QC (quality control) materials you use). Please, describe QC performance in central lab and on the POCT analyzer (in the ward).

Statistical analysis

Data were presented in tables as numbers and ratios. For each statement category ratios together with number of participants in relation to the total number of participants who answered the statement was assigned. Ratios were calculated in Microsoft office excel 2003 program (Microsoft Corporation, WA, USA). Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the accreditation status of the laboratory relative to questions dealing with the sample type, sampling procedure, blood gas sample analysis and POCT analyzers. For that purpose laboratories which are not under preparation for accreditation were considered as one group, while laboratories which are either preparing for accreditation, are in the process of accreditation or are already accredited were grouped as another group.

For questions on sample type and sampling procedure, replies in a category “never” and “rare” were grouped in one group and compared with replies in categories “often” and “always” (also grouped as one group).

Statements “I do not know” and “Not applicable” were excluded from analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant for P < 0.050. Statistical analysis was done with MedCalc software version 11.5.1 (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

First round

First round of this survey covered all acute care hospital laboratories in Croatia (N = 104). Response rate was 100%. We have identified 47/104 (45%) institutions which perform blood gas analysis either within the laboratory or under the supervision of the central laboratory. There were 3 institutions where blood gas analyzers were installed exclusively on the ward and laboratory personnel did not supervise their performance at all. Those three institutions were not included in the group of participants.

Second round

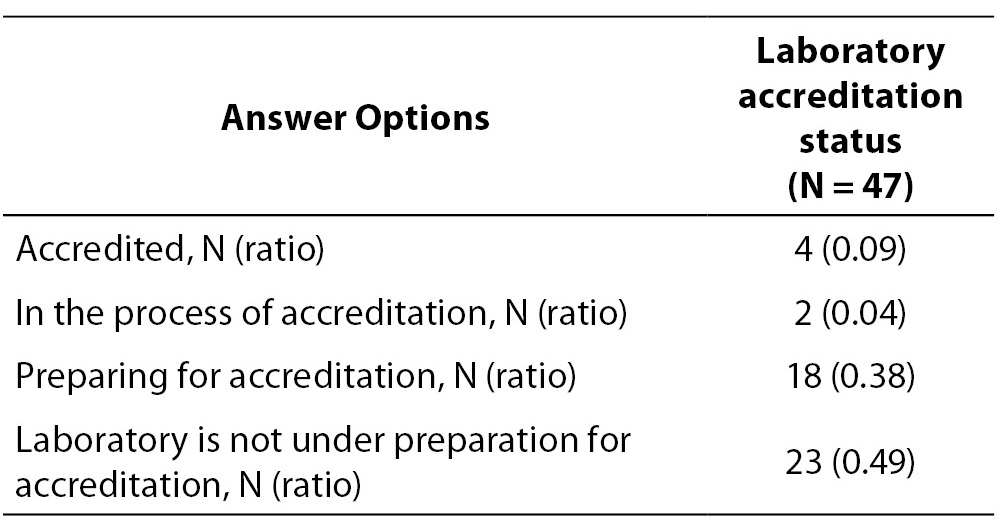

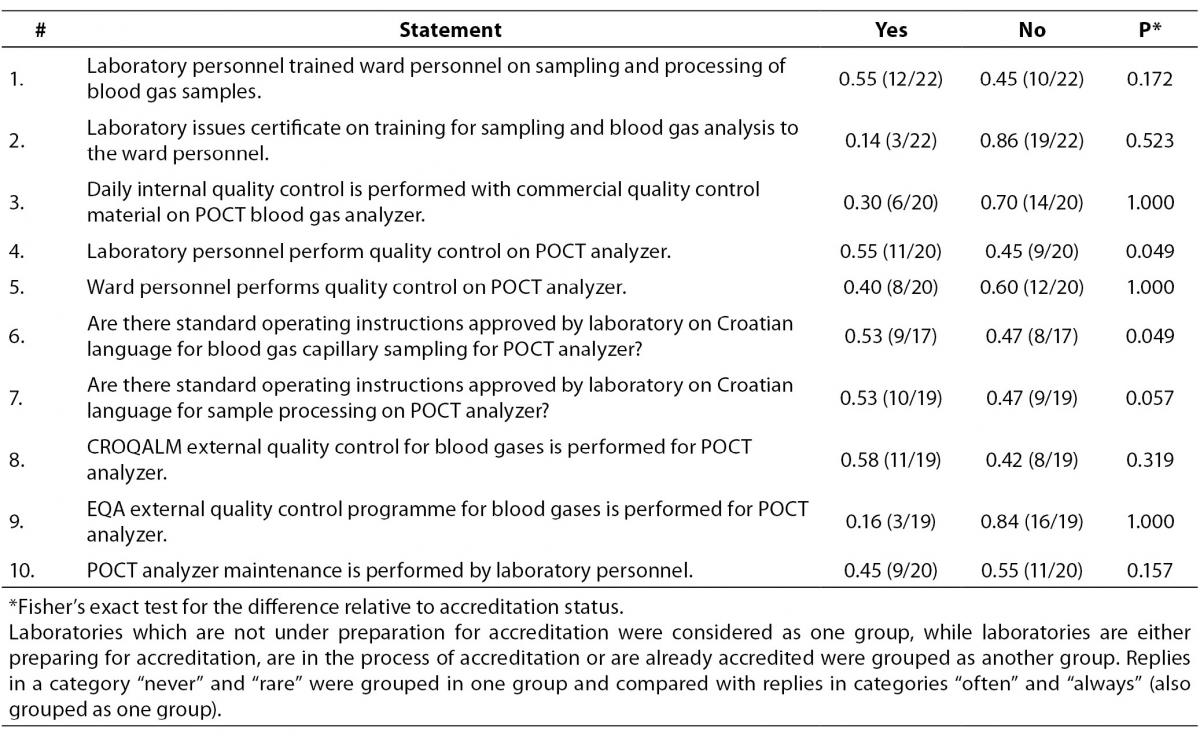

Forty seven institutions were included in the second round of the survey. General data for participants showed that 23/47 (0.49) of the laboratories are not preparing for accreditation according to ISO 15189 (Table 1). Blood gas analyzer is located within the central laboratory in 43/47 (0.92) of the laboratories, whereas 20/47 (0.43) of the participating institutions have POCT analyzers installed on clinical wards, outside of the central laboratory (14 institutions have 1 POCT analyzer, 2 institutions have 2 POCT analyzers, 2 have 3 POCT, 1 has 4 POCT and 1 has 10 POCT analyzers which are installed on various wards within institution).

Table 1. ISO 15189 accreditation status of the participating laboratories.

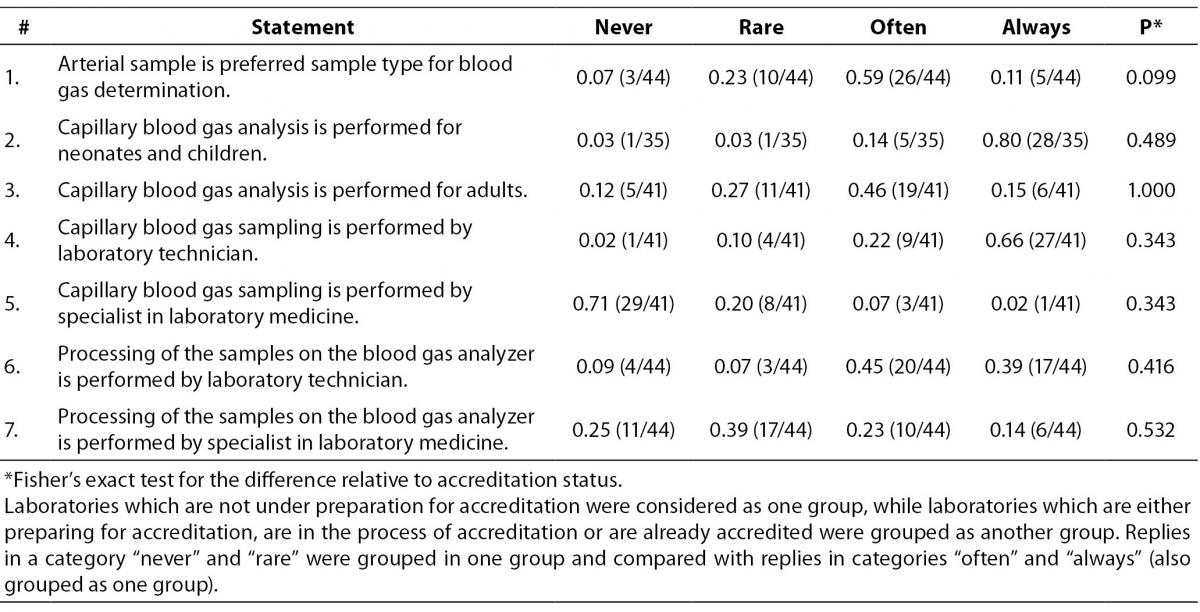

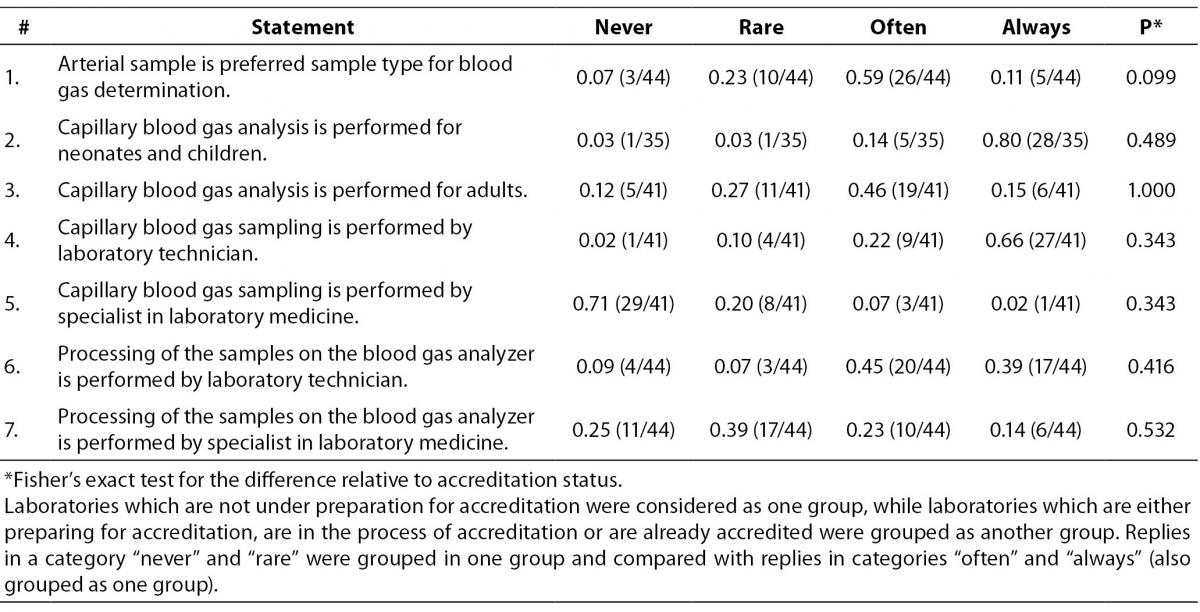

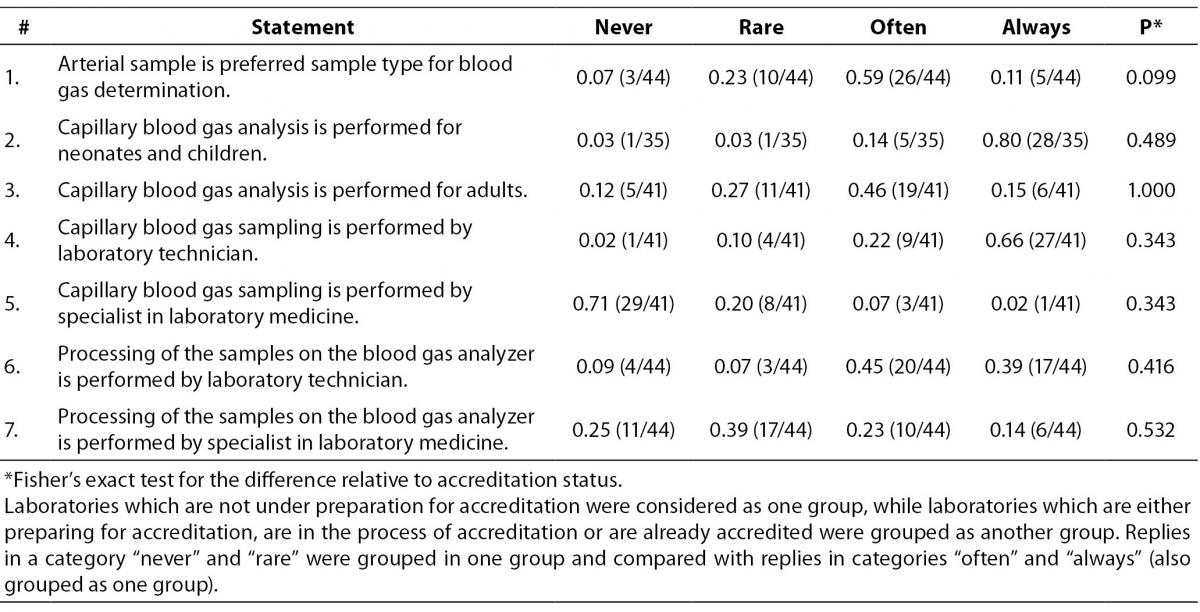

Next section of the survey covers questions related to the sample type (Table 2) which is tested on the blood gas analyzer. Only categories “never”, “rare”, “often” and “always” are shown in table. Those who replied “not applicable” were excluded from the analysis. Although participants declared that preferred sample type for blood gas analysis is arterial (26/44 or 0.59), in 19/41 or 0.46 of laboratories capillary sample is often used for blood gas analysis for adults. Laboratory technicians are performing capillary blood gas sampling in 27/41 or 0.66 of participating laboratories. Blood gas sample processing is often performed by the laboratory technicians in 20/44 or 0.45 laboratories. For this group of questions there were no significant differences between groups of accredited and non-accredited laboratories.

Table 2. Question: Sample type tested on analyzer. Ratio of participants is assigned to each category of statement. In brackets is assigned number of participants in relation to the total number of participants who answered to the statement by the quoted categories.

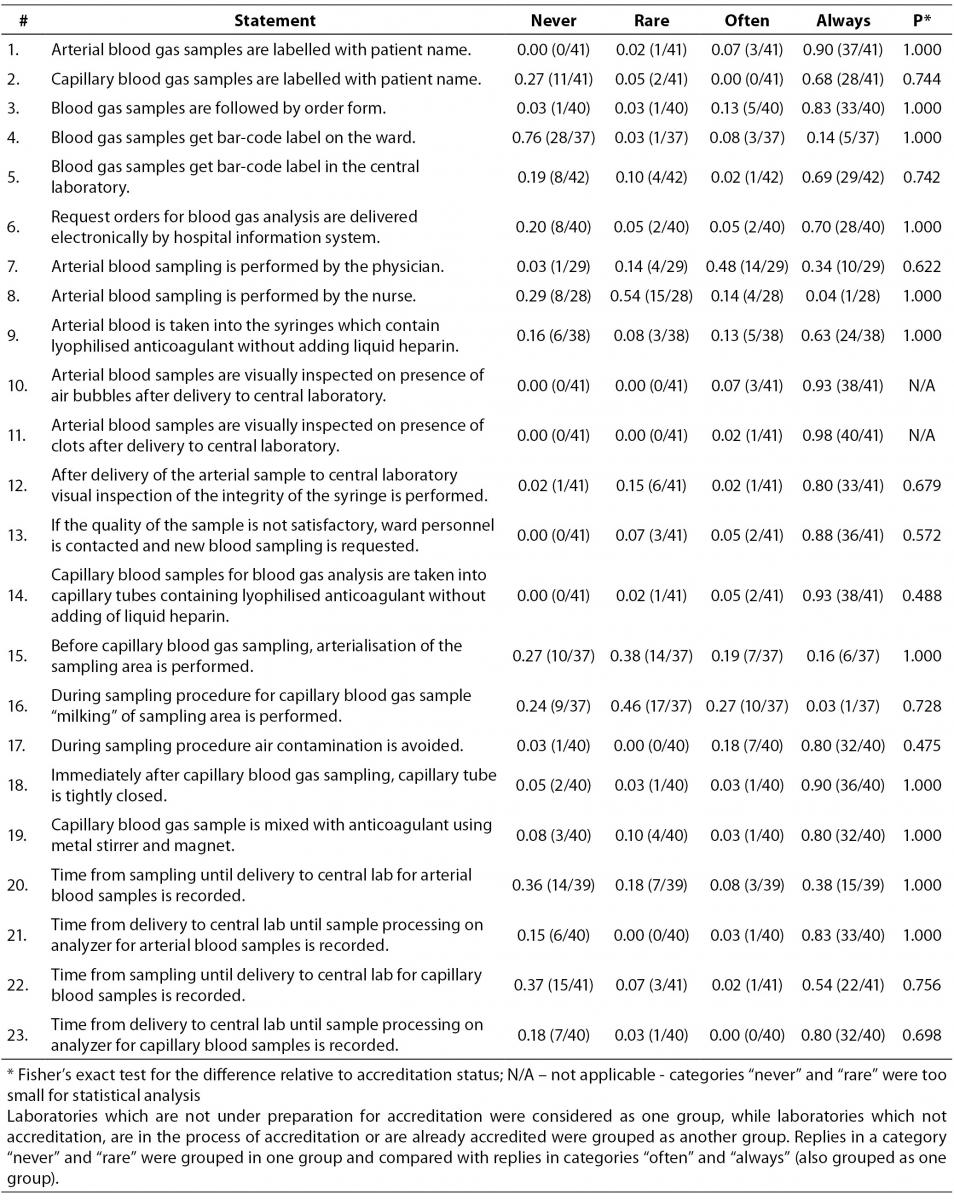

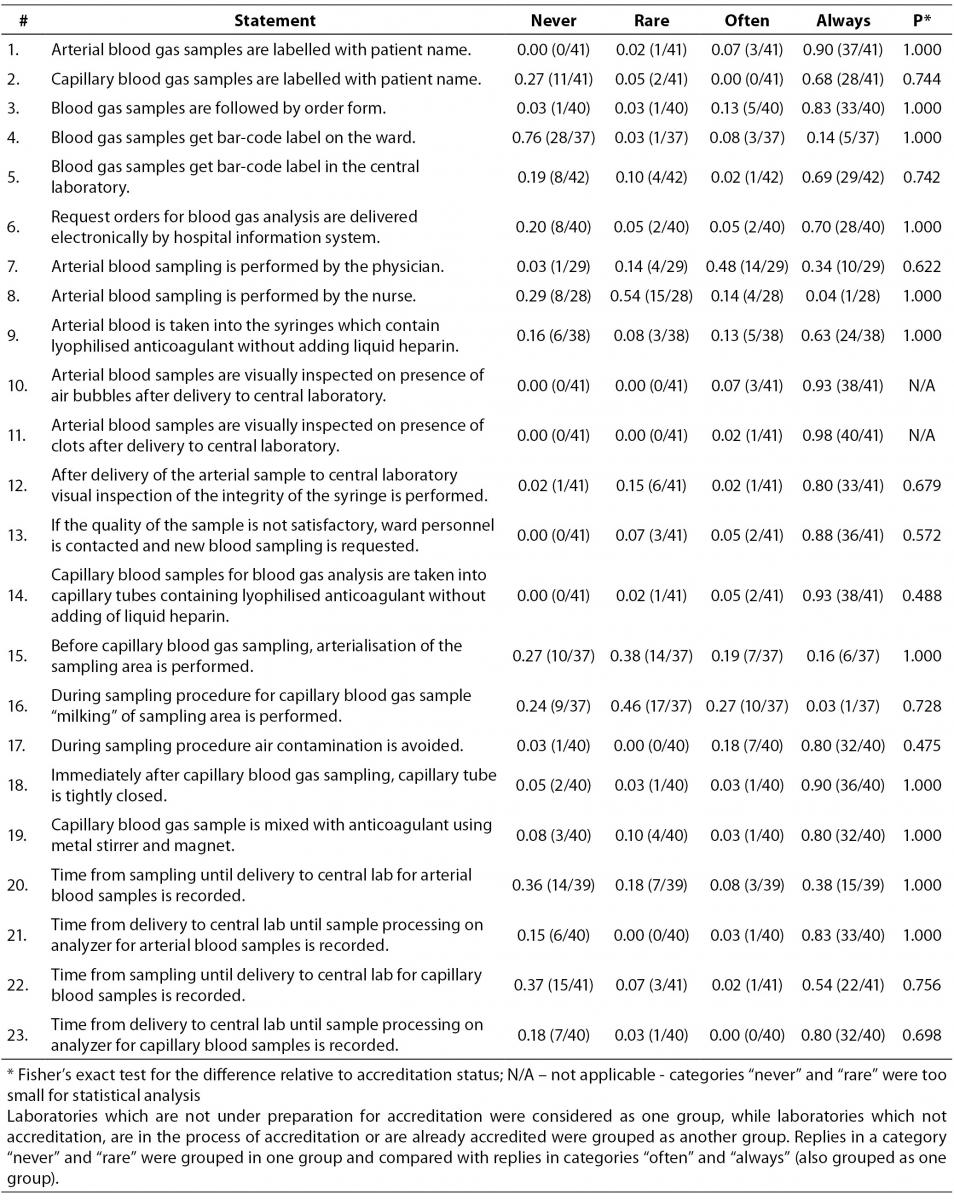

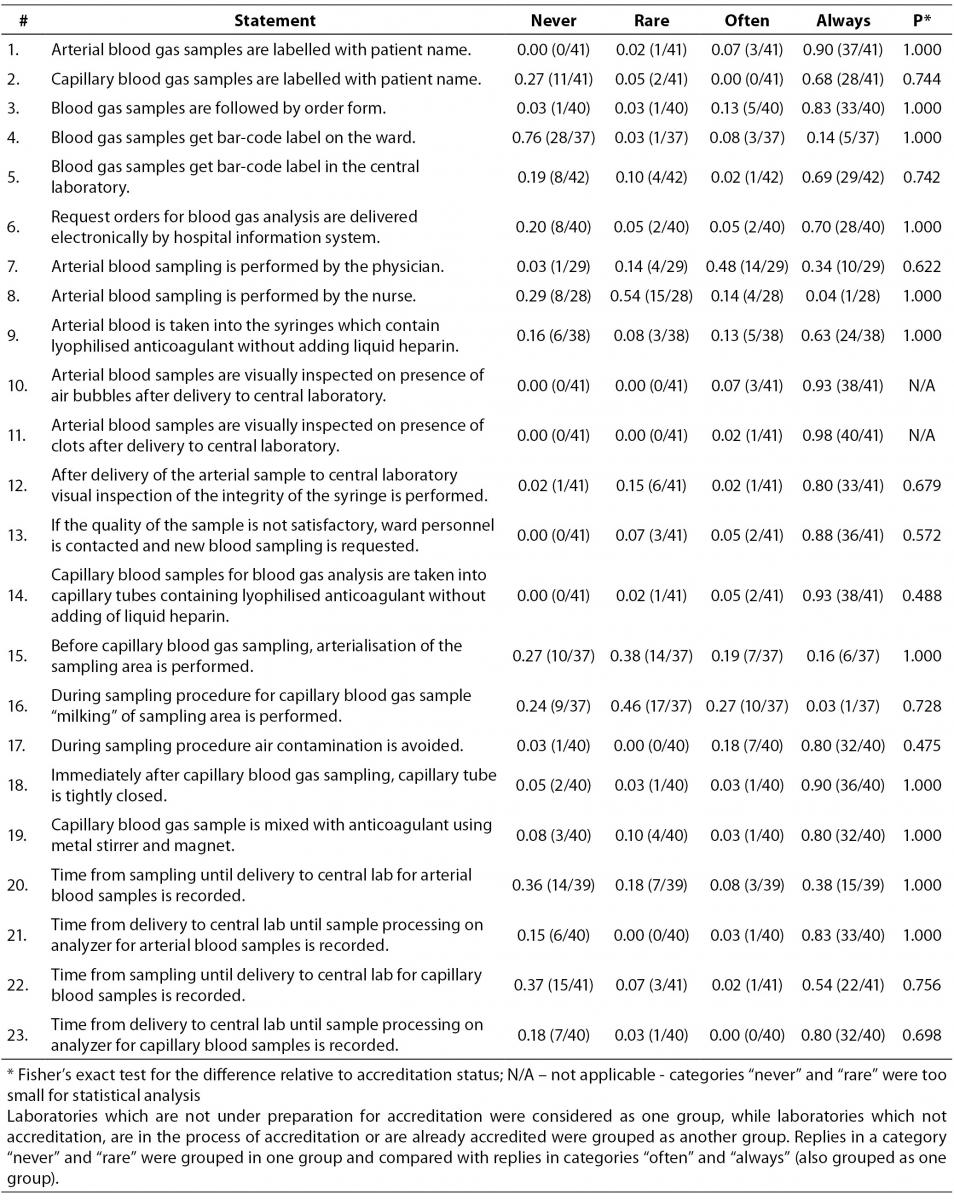

Table 3 represents data collected for statements regarding blood gas sampling procedure. Majority of laboratories follows the recommended procedure related to arterial sample labelling. Question on capillary blood samples labelling showed that 11/41 (0.27) of participants never label capillary sample, while 28/41 (0.68) of them declared they always label capillary sample. Survey showed that blood gas samples are regularly accompanied by test request forms in 33/40 (0.83) of participants and that 28/40 (0.70) of them get blood gas analyses ordered electronically by hospital information system. Interestingly, only 10/29 (0.34) of participants declared that arterial blood sampling is always done by physicians. 24/38 or 0.63 of the participants stated that arterial blood gas sample is collected into syringes containing lyophilised heparin without adding liquid heparin. Study participants visually inspect the sample for the presence of air bubbles and clots upon the delivery of the sample to laboratory. In 38/41 (0.93) laboratories capillary blood sampling is done using capillaries containing lyophilised heparin without adding liquid heparin. Arterialisation of the puncture site before capillary sampling is done rarely and never by 14/37 (0.38) and 10/37 (0.27) of participants respectively. Also, 10/37 (0.27) of participants declared that they often „milk“ the puncture site during the capillary sampling. Correct procedure of capillary blood gas sample mixing is performed by 32/40 (0.80) laboratories. Significant differences between groups of accredited and non-accredited laboratories were not observed.

Table 3. Question: Sampling procedure. Ratio of participants is assigned to each category of statement. In brackets is assigned number of participants in relation to the total number of participants who answered to the statement by the quoted categories.

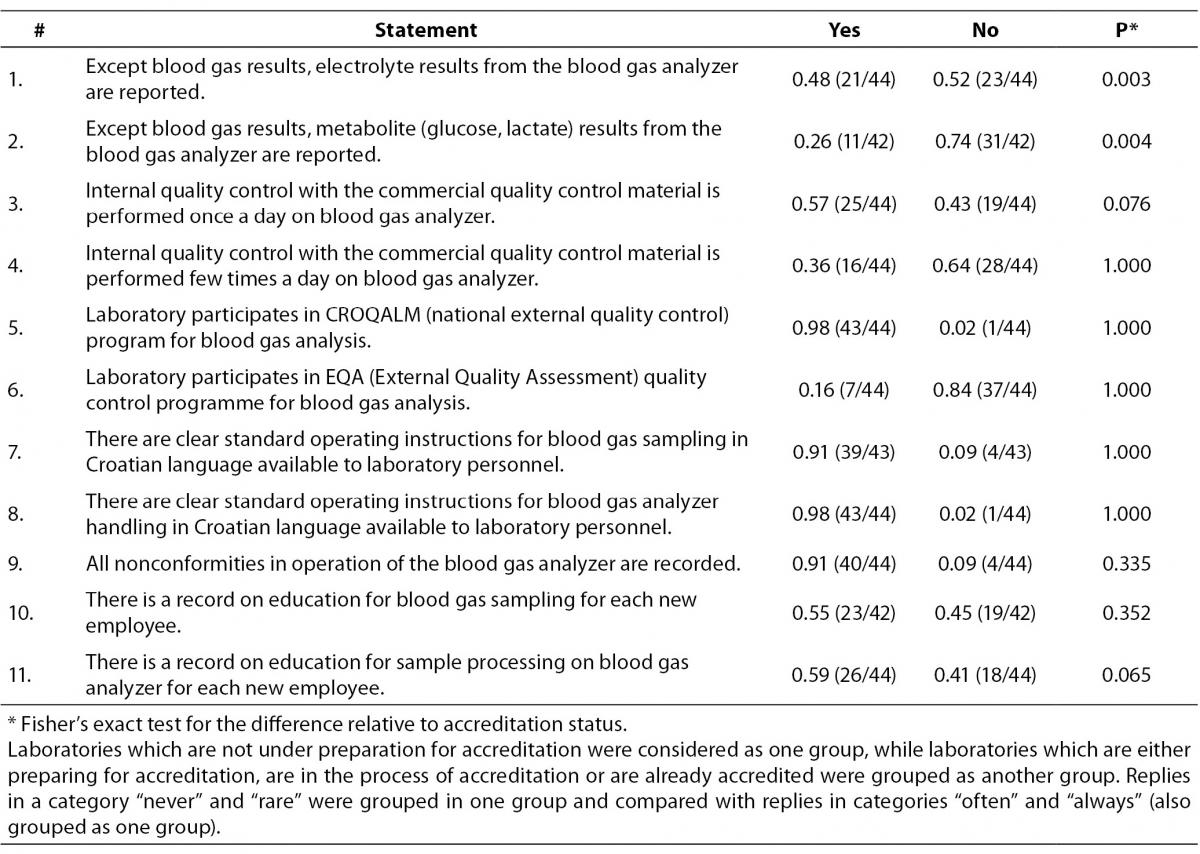

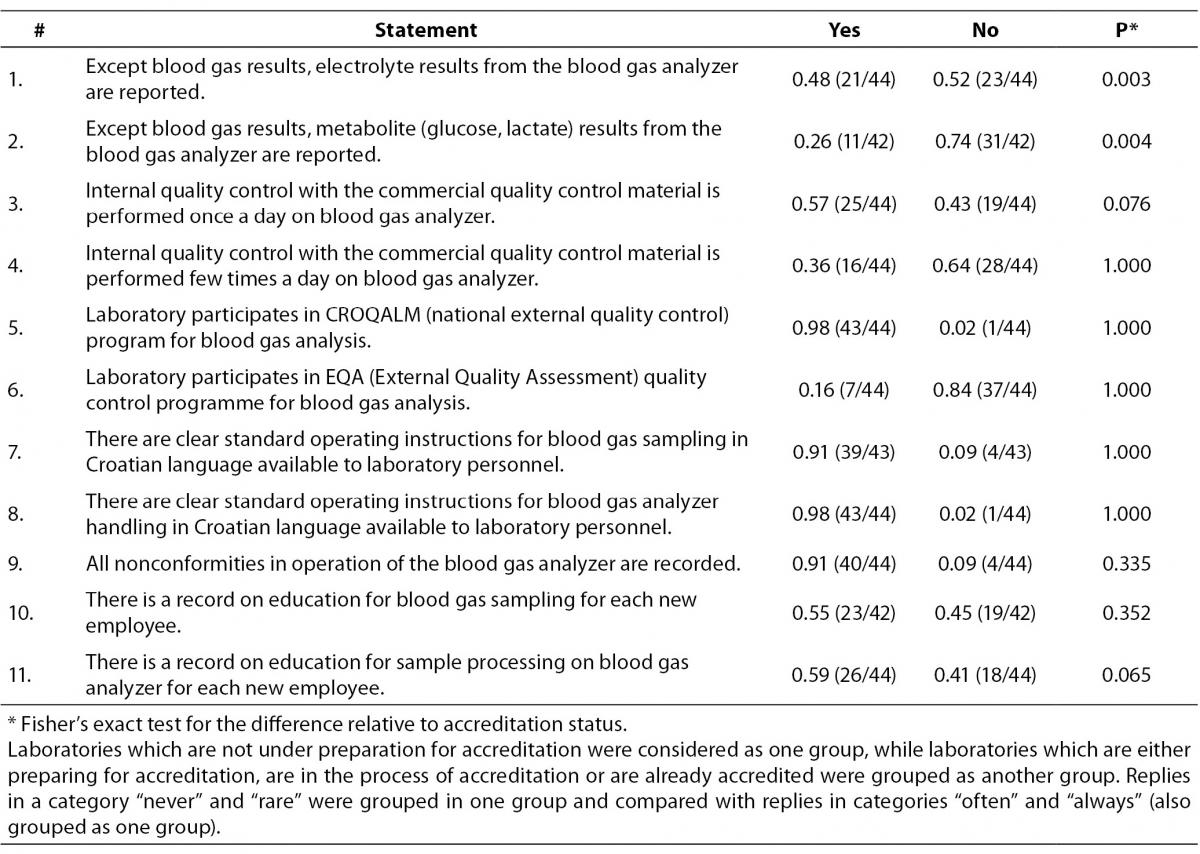

Table 4 shows data related to the way samples are processed on the analyzer in the central lab. Electrolyte concentrations measured on blood gas analyzers are reported by the 21/44 or 0.48 laboratories, while metabolite concentrations are reported by 11/42 or 0.26 laboratories. 43/44 or 0.98 of the study participants participate in the national EQA program. We found that a substantial proportion of participants do not keep records on education of laboratory personnel for sampling procedure (0.45 (19/42)) and for sample processing (0.41 (18/44)), but most of them do have written standard operating procedures available for laboratory staff. Significant difference was found for questions about electrolyte (P = 0.003) and metabolite (P = 0.004) results reporting. 16/23 laboratories from the group of those which are preparing for accreditation, are in process of accreditation or are already accredited have declared that they report electrolyte results from the blood gas analyzer, whereas only 5/21 laboratories have such practice in the group of non-accredited laboratories. Metabolite results are reported by 10/22 laboratories in the same group (accredited, in the process or in the preparation for accreditation), as opposed to 1/20 non-accredited laboratories who do not perform metabolite assays on the blood gas analyzer.

Table 4. Question: Blood gas sample analysis. Ratio of participants is assigned to each category of statement. In brackets is assigned number of participants in relation to the total number of participants who answered to the statement by the quoted categories.

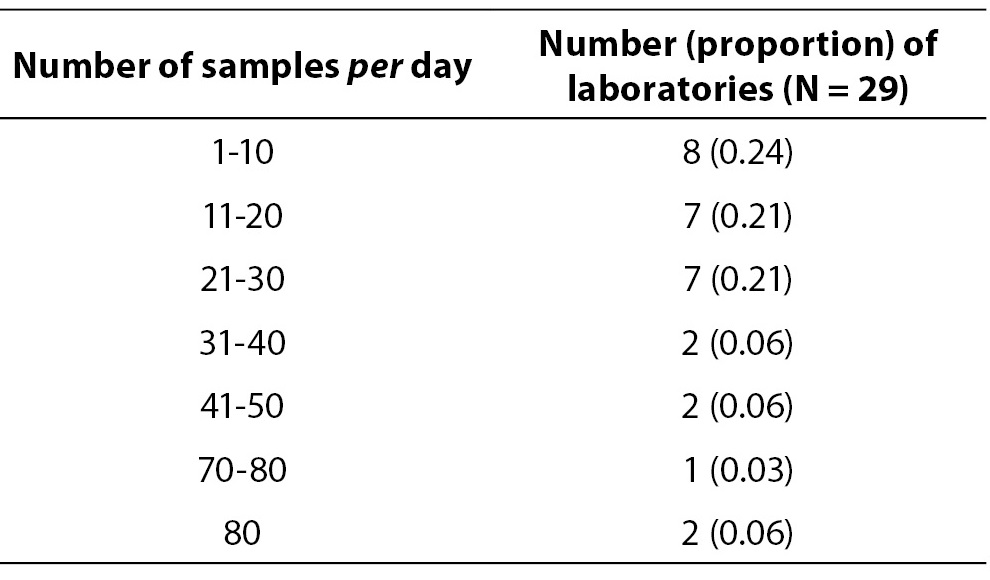

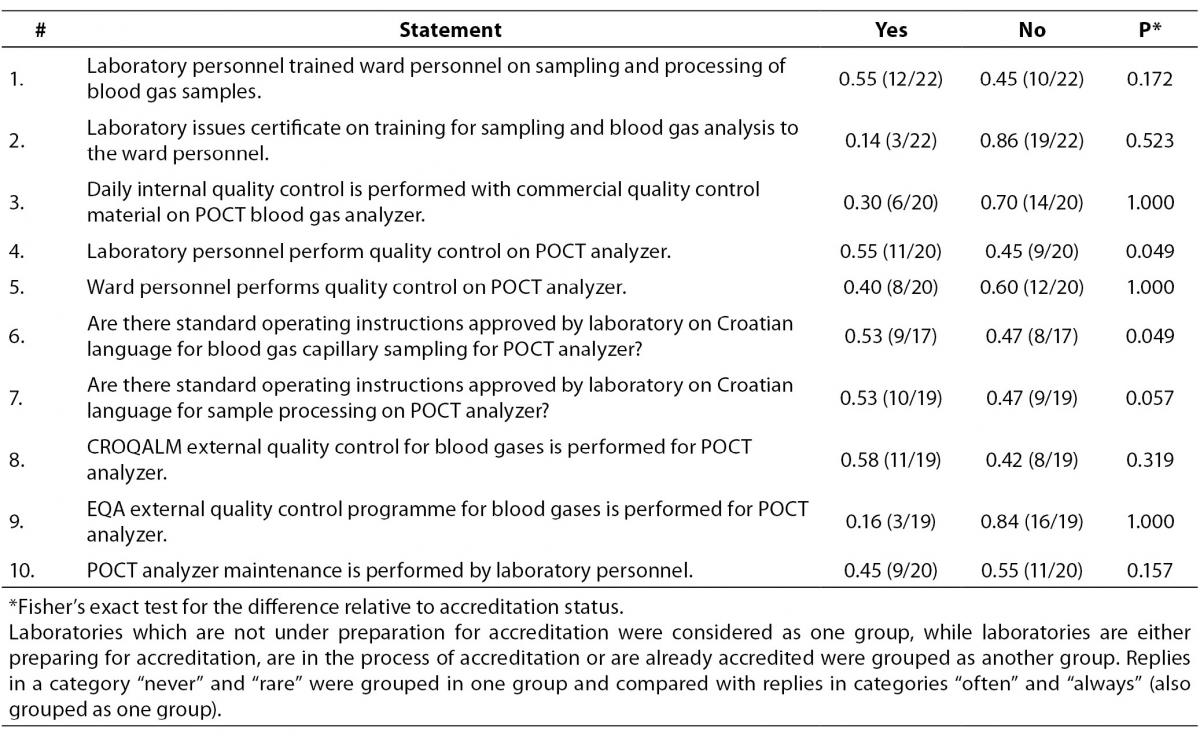

Last part of the survey was related to the questions on POCT analyzers, i. e. analyzers which are installed outside the central laboratory (Table 5). Although laboratory personnel perform education about the sampling and analysis procedures for ward personnel, laboratories do not issue certificate for this type of education. Internal and external quality control is not regularly performed on POCT analyzers. Generally, there is a great heterogeneity in the way POCT instruments are supervised by the central laboratory and the overall level of autonomy of POCT on wards was high. Practices generally did not vary relative to the accreditation status, with the exception of the following two examples.

Table 5. Questions related to POCT analyzers. Ratio of participants is assigned to each category of statement. In brackets is assigned number of participants in relation to the total number of participants who answered to the statement by the quoted categories.

In institutions where laboratories are accredited, or in the process of accreditation or are preparing for the accreditation, quality control procedures are performed by the laboratory staff in 10/14 cases, as opposed to only 1/6 among non-accredited laboratory (P = 0.049).

Standard operating instructions on Croatian language for blood gas capillary sampling for POCT analyzer are approved by laboratory in 8/11 within the “accredited-group” laboratories, whereas only 1/6 does have such instructions within the non-accredited laboratories (P = 0.049).

Third round

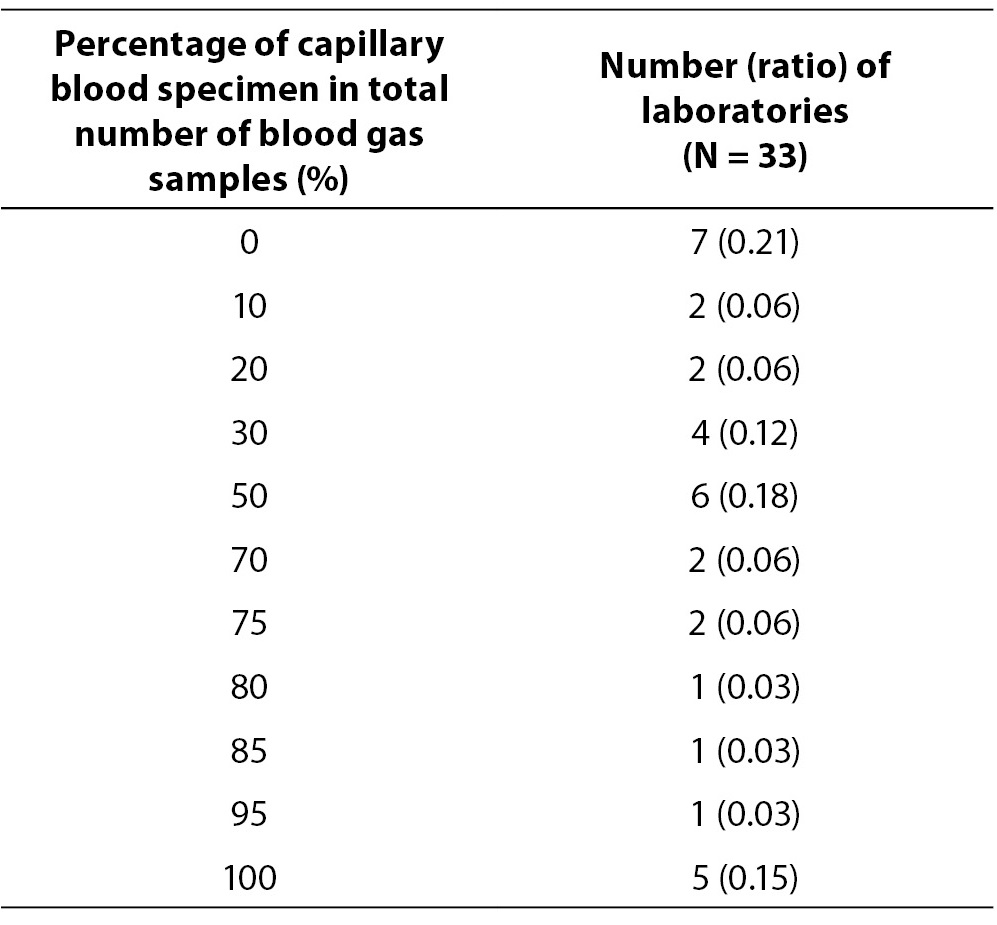

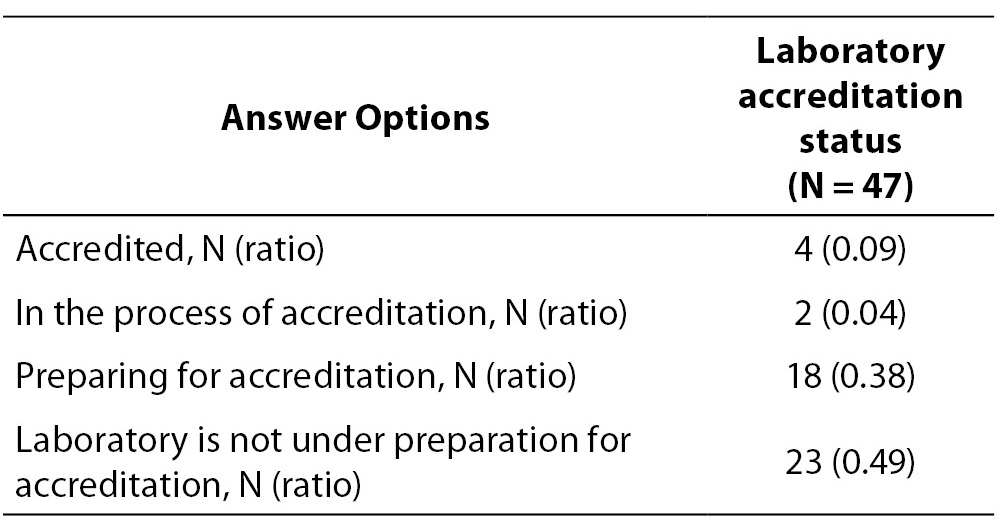

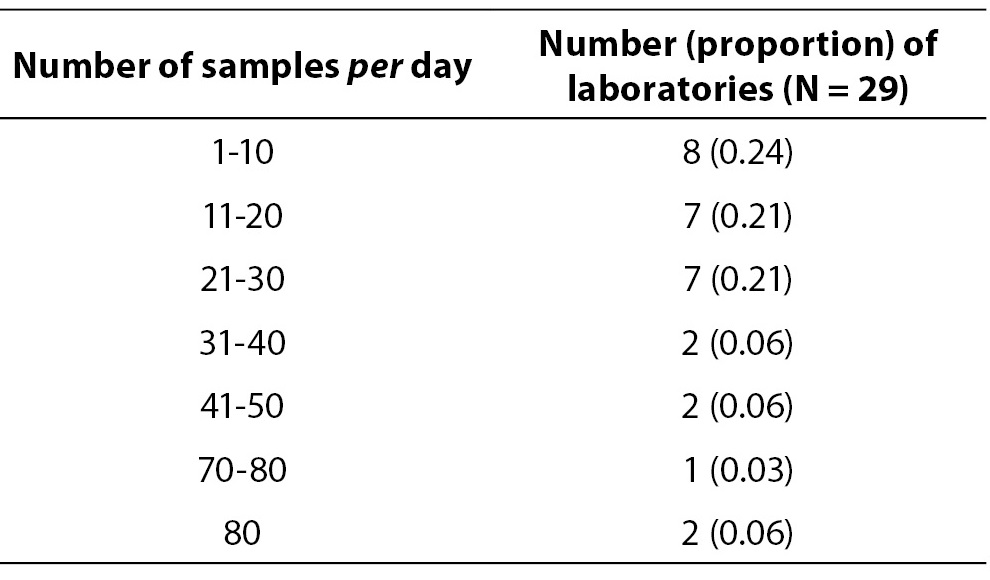

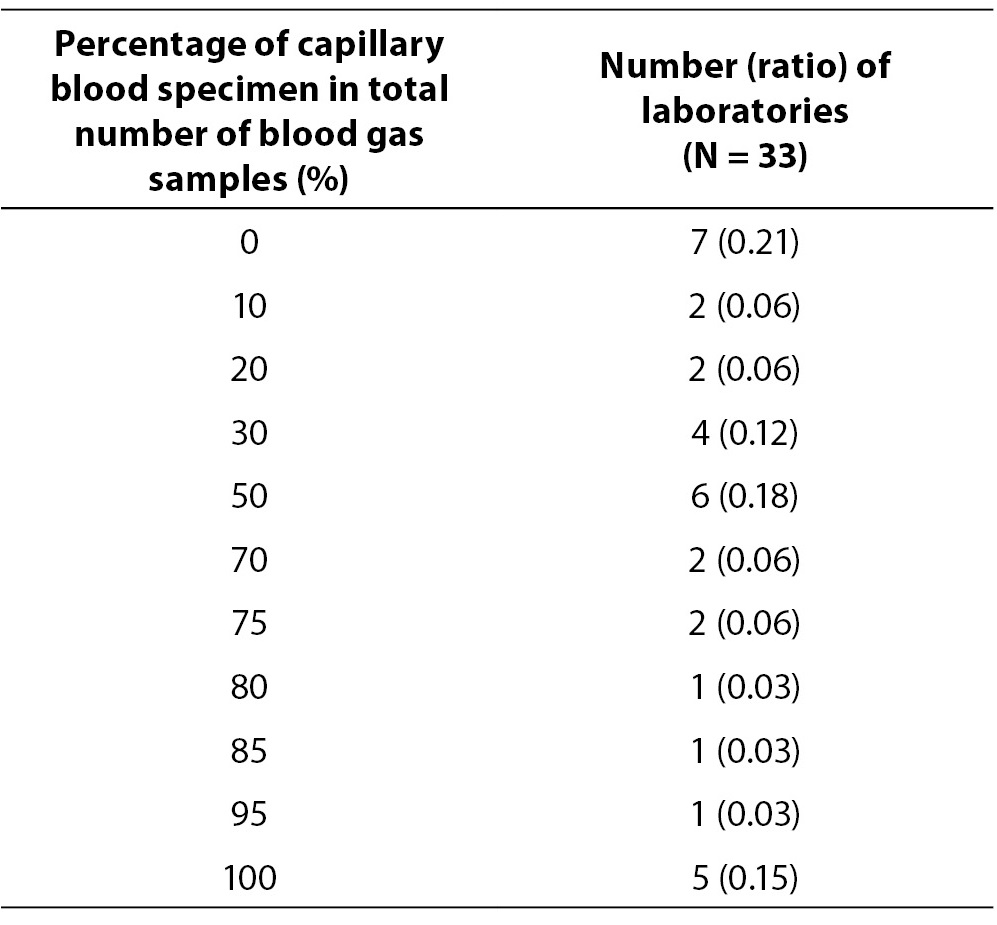

The response rate in this round was 0.70 (33/47). Data on average number of blood gas samples on daily basis are showed in Table 6. Four laboratories which perform analysis only few times per month were excluded from data analysis in Table 6. Table 7 represents number of laboratories with specific proportion of capillary blood gas samples. Only 7/33 (0.21) of the participating laboratories are exclusively analyzing arterial blood gas samples. Other laboratories predominantly use capillary sample for blood gas analysis. Four laboratories quoted that they use for blood gas analysis capillary, arterial and venous sample type. Exact procedure of capillary sample labelling was not described by 6/33 (0.18) of participants, although additional question was asked to allow exact description of the labelling procedure for the capillary sample. Direct labelling of the capillary sample is performed in 10/33 (0.30) of laboratories. 31/33 or 0.94 of laboratories does not keep record of the time of sampling, delivery and processing of the blood gas specimen. Quality control is not regularly performed (at least once a day, using commercial control materials) in 15/33 or 0.45 of the laboratories.

Table 6. Average number of blood gas samples per day.

Table 7. Percentage of capillary blood specimens. In brackets is assigned ratio of laboratories in relation to the total number (N = 33).

Discussion

Result reliability is imperative in emergency patient care. Technological achievements enabled high level of reliability for analytical phase of sample processing. New tools for error prevention and quality improvement in pre- and post-analytical phase of the testing are introduced in laboratory practice (8,9). Improvement in laboratory diagnostics created basis for harmonization of all operating procedures (10). There is necessity to introduce uniform set of objective, measurable indicators (11,12) which will enable each laboratory to monitor, detect and eliminate errors in total testing process.

One important step toward harmonization is for sure establishment of detailed guidelines for various procedures used in laboratory diagnostics. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute published documents related to pH and blood gas analysis (4,5). These documents serve as valuable landmark for introduction of higher standard in laboratory diagnostics of acid-base balance.

Survey studies were conducted on national level for pre- and post-analytical phase of testing (13,14) for identifying most frequent sources of errors and reducing them. Survey on extra-analytical phase of testing was done among members of Croatian Chamber of Medical Biochemists during 2009. and results showed that special attention should be payed to improvement of phlebotomy performance in order to minimize errors. National cross-sectional study on critical value reporting was performed in Chinese laboratories and authors found lack of standardization related to critical value reporting. To the best of our knowledge, there are no publications on survey on blood gas sample collection and analysis available.

Accreditation regulations serve as valuable tool in risk management and quality improvement in laboratory setting (8). Accredited laboratories are constrained to work on quality improvement. They tend to respect recommendations and reduce nonconformities.

Capillary sample is preferred sample type used for blood gas analysis in most of the institutions on the field of Croatia. Small proportion of institutions which perform exclusively arterial blood gas analysis proves that practice of routine or standing orders for capillary blood gas sampling is still common practice performed by physicians. The fact that capillary blood gas sample is preferred in prevailing number of institutions can be attributed to the traditional and economical reasons. Traditional reasons are related to habitual practice of physicians regarding capillary blood gas ordering in some institutions. Current documents recommend capillary sample type only in situations when arteries are not accessible for adult patients and for blood gas analysis on neonatology and paediatric department (15). Arterial sample is needed for objective assessment of patient oxygenation status by hemoxymetry (16). Capillary blood sampling for blood gas analysis as routine or standing order is not recommended (17).

According to survey results, regulations regarding sample labelling are not respected when capillary sample is concerned. Capillary tube should be labelled directly by the label with the patient data (18).

In Croatian health care institutions, arterial specimen collection is responsibility of physicians. Laboratory is responsible for preanalytical phase of the testing process which takes place on the ward (6). Many survey participants are not informed who exactly performs arterial blood collection. High-quality specimen which is not contaminated by air and clots depends on syringe type, anticoagulant and sampling procedure used by physician (19). High level of communication between ward and laboratory personnel is needed for avoiding problems with blood gas analysis caused by inappropriate arterial sampling and transport.

All the procedures related to visual specimen control which are needed upon sample delivery to the central laboratory are highly respected by the survey participants. Generally, most of the procedures related strictly to laboratory like sample integrity control are performed in accordance with current standards (5).

When capillary blood gas sampling procedure is concerned, there is heterogeneity in approach of each institution. In order to get sample as similar as possible to the arterial sample, strict following of all the steps which include arterialisation, filling of capillary tube and mixing is needed (20). Arterialisation of puncture site is not regularly performed by the great proportion of laboratories. “Milking” of puncture site during specimen collection should be avoided because of impact on pH, blood gases and electrolyte measurement (17). For proper anticoagulation of the specimen it is necessary to mix specimen with metal stirrer and magnet (5). Many laboratories do not perform all the steps in capillary blood sampling which are needed to get sample as much as possible similar to the arterial. Those laboratories which have very low number of requests for blood gas analysis usually stick to the recommended procedures, while those which have high number of requests tend to exclude important steps of the sampling procedure and risk to report unreliable results.

Survey showed that some laboratories report not only blood gas results, but also electrolyte and metabolite results from the blood gas analyzers. Whole range of preanalytical issues and matrix differences represents danger to reliable reporting from different analytical platforms. Non-detectable hemolysis causes false positive potassium findings in the first instance, but it has significant impact on other tests (21,22). In comparison study of point-of-care blood gas analyzer and biochemistry analyzer, significant difference was found for sodium values, while potassium values were comparable (23). Study was performed on 200 paired venous and arterial samples. Venous samples were tested on biochemistry analyzer Dade Dimension RxL, while arterial samples were analyzed on blood gas analyzer ABL 555. Simultaneously tested arterial and venous patient samples on blood gas and biochemistry analyzer showed unacceptable agreement for sodium and potassium, respectively (24). Authors retrospectively analyzed data and found 84 simultaneously tested venous and arterial specimens for electrolytes. Venous specimens were tested on biochemistry analyzer Roche Modular P, and arterial specimens were tested on Nova Biomedical pHOx Stat Profile Plus L blood gas analyzer.

Internal quality control schemes on blood gas analyzers showed significant differences which are dependent on average number of blood gas samples analysis per day and economical resources of the laboratory. Almost all laboratories participate in national program for external quality control. In order to assure analytical reliability of the blood gas testing, daily measurement of the different levels of quality control materials is needed (25).

Considering the fact that there is no consistency in training of non-laboratory personnel for blood gas analyzers, regular quality control and maintenance of the POCT analyzers, special attention should be paid to establishment of the document which will regulate jurisdiction of the central laboratory for POCT (26).

Supervision of POCT analyzers is not standardised. Introduction of bed-side blood gas analyzers improved overall patient care, but strict precaution measures are needed (27). Survey results showed that group of laboratories which are accredited or in process of accreditation are responsible for providing operating instructions related to blood gas capillary sampling and take much more care about the quality control performance on POCT analyzers.

Correct recording of the time of sampling, sample delivery and processing for blood gas assays is not very common.

This study was a self reported survey which might not be providing the accurate and reliable information about the real situation, since respondents could have been providing desirable answers, instead of declaring the real situation in their institution. We are aware that observational studies have much more power to detect deviations from the standard procedures and non-conformities in the process, in comparison with surveys. This could as well be one possible limitation of our study.

Conclusion

Practices related to collection and analysis for blood gases in Croatia are not standardised and vary substantially between laboratories. POCT analyzers are not under the direct supervision by laboratory personnel in a large proportion of surveyed institutions. It is essential to provide a framework for nation-wide harmonization and standardization of laboratory procedures related to blood gas analysis in Croatian laboratories.